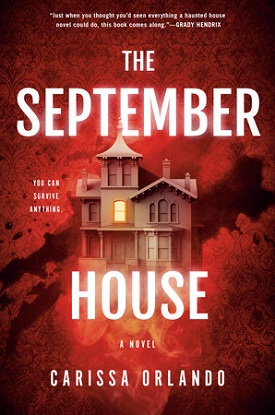

Synopsis:

Synopsis:

When Margaret Hartman and her husband, Hal, bought the large Victorian house on Hawthorn Street for a surprisingly reasonable price, they couldn’t believe their dream of owning a home of their own had finally come true.

Then they discovered the hauntings.

Every September, the walls drip blood. The ghosts of former inhabitants appear, and all of them are terrified of something that lurks in the basement.

Most people would flee.

But Margaret is not most people. Margaret is staying. It’s her house.

However, after four years, Hal can’t take it anymore and leaves abruptly. He’s not returning calls and his voice mail is full. Their twenty-nine-year-old daughter, Katherine, knows nothing about the hauntings, but is intent on visiting for the first time in order to search for her missing father.

To make things worse, September has just begun. With every attempt Margaret and Katherine make to find Hal, the hauntings grow more harrowing . . . because there are some secrets the house needs to keep.

Review:

Debut author Carissa Orlando holds a doctorate in clinical-community psychology and specializes in working with children and adolescents. She is committed to improving the quality of and access to mental health care for children and their families. Orlando says she has written creatively in some form since she was a child and studied creative writing in college. She has long been an avid horror fan so the merger of her knowledge of the workings of the human psyche and love for storytelling was probably inevitable and, with The September House, is demonstrably seamless.

Margaret Hartman and her husband, Hal, longed to own an older home, preferably Victorian. Both of them grew up in fairly transient families, and throughout their marriage they moved from one rental to another, all the while wishing for a permanent, stable residence. Hal taught at the community college and worked as a freelance writer while striving to get his books published. Margaret worked various jobs (retail, administrative assistant, substitute teacher) while focusing on raising their daughter, Katherine, and painted as time and funds allowed. Eventually, Hal sold and began receiving royalties from his books and Margaret showed a few paintings at a local gallery. Katherine graduated from college and launched her own career, and the dream of home ownership was abandoned.

Until Margaret saw the listing for the beautiful cobalt blue house with white trim, a wrap-around porch, and a turret. She immediately recognized it as their dream house. It even boasted rooms that would make a perfect office for Hal and a studio with plenty of sunlight for Margaret. The shockingly low sales price should have served as a warning. When they toured the house – in which no one had resided since sometime in the 1990’s – and were informed by the real estate agent that two deaths took place in the house more than one hundred years ago, they “were barely listening, busy picturing ourselves sipping morning tea in bed, looking out” the master bedroom’s impressive picture window, Margaret recalls. Margaret was so overjoyed at the sight of a claw-foot bathtub in the master bathroom that she didn’t even hear the agent mention the “other deaths in the house” that “seemed to be natural in nature.” Even the dank smell, coupled with the goosebumps Margaret developed in the unfinished, windowless basement with dirt floors that had a “bit of a wrong sense” about it wasn’t enough to dampen Margaret’s enthusiasm. Neither she nor Hal noticed that the agent did not descend the stairs to the basement with them. They went ahead with the purchase and moved into the house in May. At first, Margaret insists, everything was “blissful.”

But in September, the situation began deteriorating. Blood started running out of and down the walls, seeming to originate right over their bed in the master bedroom. The sound of moaning escalated to all-out screaming that continued all night, making it extremely difficult to sleep. Margaret adapted to the mysterious goings-on. “Eventually, one has to give up asking questions, just accept that things are the way they are, and act accordingly,” she explains in her first-person narrative that Orlando employs to tell the story. Fredricka, a maid, appeared with a large gash on her head — where the blow from an axe landed and killed her. Fredricka still performs household tasks, but has trouble operating the toaster (she prefers to roast the bread over a fire the way she did when she was alive a century ago) and in September she moves things around, placing them in nonsensical places and positions. Margaret discovers that if she touches Fredricka, she is whisked back in time to the fateful moment the axe was swung by Fredricka’s attacker, experiencing it from Fredricka’s perspective. A boy about nine or ten years old, Elias, also manifested. He refuses to speak, but howls and uses his long, sharp fangs to bite Margaret if she forgets that he doesn’t “like his personal space invaded.” His stares were “initially unsettling, but one grows used to unsettling things,” Margaret observes. There’s also Angelica, a little girl with sallow skin and one eyelid drooping from its socket, who stands in front of the basement door, pointing and telling Margaret, “He’s down there.” That’s where Master Vale, the former owner, resides.

After living in the house for several years, Hal could no longer tolerate the supernatural goings-on. Margaret explains that he begged her to leave the house with him, but she refused to surrender her home to their other-worldly co-inhabitants. So Hal left without her. Weeks have gone by, and she has heard nothing from him. Worse, she never told Katherine that Hal left and now their daughter is frantic because Hal does not answer his phone, or respond to voice or text messages. When Katherine announces that she is coming to stay with her mother so that she can look for her father, Margaret becomes frantic. Katherine was largely estranged from her father (for reasons that become clear as the story progresses) so Margaret is somewhat baffled by her intense concern for Hal. Worse, Katherine will be arriving in September, the month in which paranormal activity in the house grows more intense every year. More children join Angelica, the relentless screams become louder, the volume of blood pouring from the walls increases, and Fredricka’s illogical re-arranging of furniture, and household and personal items, occurs more often. There are also the numerous birds that fly suicidal missions directly into the home’s windows, requiring Margaret to gather and dispose of the carcasses.

Margaret has no friends except her neighbor, Edie, who is a bit of a busybody and loves to visit with Margaret on the front porch. Edie is pleasant — squat and motherly – and has never questioned the truth of Margaret’s reports about the eerie events that take place in the house. Hal disliked Edie from the moment they met and she launched her nosy inquiries. As Margaret ponders how to keep the truth from Katherine, Edie commiserates, “Oh, Margaret, you’re in a real pickle.” That’s an understatement.

Katherine arrives and, with Margaret, begins visiting every bar in the area to see if Hall has been seen there. Margaret gradually reveals Hal’s struggle with alcoholism that ultimately led to four arrests for driving while under the influence and the rescission of his driver’s license. Which is why he left in a taxi. They also look for him in the local motels and hotels.

Margaret is a sympathetic character, but highly unreliable narrator, and Orlando’s choice to tell the tale in her voice from her unique perspective is highly effective, heightening the suspense. Whether Orlando has crafted a straight-forward horror story, a psychological thriller, or melded the two genres is not immediately apparent. Margaret is earnest and convincing as she relates the details of her interactions with the spirits who inhabit her house. She insists that, aside from the month of September, it continues to be the home she always wanted, and she is stubbornly adamant about remaining there, even though Hal has departed. She feels compassion for the ghosts who are seemingly trapped there and researches the history of the home to gain an understanding of how their lives came to such tragic ends. In an effort to quell the annual disruptions, she repeatedly enlists the help of an elderly local priest who blesses each room. During his final visit, he ventures into the basement, even though the entrance has remained boarded up since an earlier terrifying incident with Master Vale. The priest’s visit makes matters worse.

Katherine’s relationship with her parents has been fraught due to her father’s addiction, the behavior in which he engaged as a result of it, and her mother’s response and choices. Katherine is a very angry young woman who admits that her relationship with her girlfriend has ended, in part, because of her own inability to manage her emotions. Her frustrations have always mushroomed into inappropriate outbursts and full-blown tantrums, but Margaret observes that Katherine is better able to control herself, likely because, as she confesses, she has recently sought therapy. Katherine’s efforts to improve herself and commitment to her parents, despite their shared past, endears her to readers.

What emerges is a depiction of a woman with a family history of mental illness who remained in a deeply troubled marriage. Margaret insists that “everything is survivable” if one simply follows the applicable rules. It becomes clear that she did everything in her power to adhere to the rules governing her marriage to Hal, but did not always succeed. And she has co-existed in her beloved house by adapting rules designed to make her ghostly roommates’ conduct bearable. Devoted to Katherine, Margaret recognized that it was her duty to protect her child and committed herself to that task. But, of course, she was unable to hide the truth from Katherine, and Katherine’s palpable resentment caused her to distance herself from her parents for years. Until now. Aghast that, even though Hal disappeared weeks ago, Margaret never filed a report with the local police, Katherine involves law enforcement in the search as the September days elapse, the spirits’ activities become more pronounced, and Margaret grows increasingly sleep-deprived and nearly incoherent.

The September House proceeds at a rapid pace as details about Hal’s whereabouts emerge and “the pranksters” – as Margaret calls them – respond. A gory, dramatic confrontation tests both Margaret and Katherine, and reveals that Orlando’s story is a clever, multi-layered, allegorical examination of destructive power imbalances in relationships, abuse, family secrets, and the psychological and emotional effects of trauma. It is also an illustration of resilience, resolve, and the freeing and healing power of the truth. Orlando wisely gives readers respites from the deep and relentless emotional intensity of the story with slyly comedic moments. Some of Margaret’s conversations with the pranksters are hilarious, and her visits with Edie are charmingly humorous. But as utterly ridiculous and outrageous as many of the characters’ actions are, Orlando never allows the story to lose focus, delivering clues at well-timed junctures about how Margaret’s decisions and choices landed her in the middle of a horror story. Perhaps. Or is she suffering from some type of psychotic break that has caused her to imagine that paranormal activity is occurring in the house? Does Katherine see and hear the ghosts, as Hal did (accordingly to Margaret, at least)? Do the police who come to investigate Hal’s disappearance see and hear them? Why does Edie, who never enters the house, instead remaining on the porch during her visits, unwaveringly accept as true Margaret’s representations of the goings-on in the old Vale house? Learning the answers to those and other mysteries is a surprisingly entertaining and moving experience. Orlando so skillfully reveals the Hartman family history and how it has shaped the psyches of Margaret and Katherine that they become empathetic characters for whom readers will cheer, counting on Orlando to bring their stories to a satisfying conclusion. She does not disappoint. The September House is an impressive and promising debut.

Excerpt from The September House

One

The walls of the house were bleeding again.

This sort of thing could be expected; it was, after all, September.

The bleeding wouldn’t have been so bad if it hadn’t been accompanied by nightly moaning that escalated into screaming by the end of the month like clockwork. The moaning started around midnight and didn’t let up until nearly six in the morning, which made it challenging to get a good night’s sleep. Since it was early in the month, I could still sleep through the racket, but the sleep was disjointed and not particularly restful.

Before Hal absconded to wherever it was he went, he used to stretch and crack what sounded like the entirety of his skeleton. Margaret, he would say, we’re getting old.

Speak for yourself, I would reply, but he was right. I was starting to feel a bit like the house itself sometimes-grand but withering, shifting in the wind and making questionable noises when the foundation settled. All the moaning-and-screaming business in September certainly didn’t help me feel any younger.

That is to say, I was not looking forward to late September and the nightly screaming. It was going to be a long month. But that’s just the way of things.

As for the bleeding, it always started at the top floor of the house-the master bedroom. If I wasn’t mistaken, it started above our very bed itself. There was something disconcerting about opening your eyes first thing in the morning and seeing a thick trail of red oozing down your nice wallpaper, pointing straight at your head. It really set a mood for the remainder of the day. Then you walked out into the hallway and there was more of it dripping from in between the cracks in the wallpaper, leaking honey-slow to the floor. It was a lot to take in before breakfast.

As early as it was in September, the blood hadn’t yet made it to the baseboards. Give it a week, however, and it would start pooling on the floor, cascading down the stairs in clotting red waterfalls. By the end of the month, deft footwork would be required to walk down the hallway or descend the stairs without leaving a trail of prints throughout the house. I had grown practiced in dodging blood over the past few years, but even I had slipped up on occasion, especially once the screaming was in full effect. Sleep deprivation really takes a toll on your motor functioning.

I used to worry over the walls, getting a bucket and soap and scrubbing until my arms were sore, only to see my work undone before my eyes. I would rub the sponge over a crack in the wallpaper and watch a fresh blob of red leak out of the open wound that was the wall over and over again. The wallpaper is ruined, I fretted, but it never was. It all went away in October. So now I just allowed the walls to bleed and waited patiently.

The first year we were in the house, Hal tried to convince me that the bleeding was just a leak. An oozing red leak. He carried on with that line of reasoning much longer than was logical. By the time the blood poured down the stairs and Hal was almost ready to admit that maybe it wasn’t a simple leak, October hit and the blood vanished. Hal considered it a problem solved. I suppose he thought it was an isolated event and never considered that such a thing might be cyclical. He seemed surprised when the blood returned that second September. There’s that leak again, he mused, fooling nobody. Everything, of course, changed after the third September, and Hal’s opinions about the bleeding during this fourth September could be best summed up by his abrupt absence. I supposed I ought to feel trepidatious about facing September alone. However, I was never quite alone in this house, now, was I?

I couldn’t tell you why the walls bled. I couldn’t tell you why there was screaming at night. I couldn’t tell you why a lot of things happened in this house. Over the years, I had developed a few working theories about the goings-on and why September made everything so much more difficult, but each was half-formed at best. Eventually, one has to give up asking questions, just accept that things are the way they are, and act accordingly. So when I woke up to a wall dripping with blood and to a foggy head from not-quite sleeping through hours of moaning, I simply nodded and got on with my morning.

My only plan for the day was to try to get some painting done. I had learned from past experience that it became difficult to focus on painting or really much of anything as the month progressed, what with the sleep deprivation and the blood and the loud noises and the wounded children running everywhere. As such, I wanted to front-load my pleasures in the hopes that they could carry me through the remainder of the month. Planning is important. So I set myself up in my sunroom studio with a blank canvas, hoping for inspiration. However, I soon found myself staring at a canvas painted entirely in red, which seemed a bit derivative, given the circumstances.

I tapped my paintbrush against my lips and stared at the red canvas, plotting out what to paint. It might have been nice to do a nature scene-some peaceful flowers, waving trees-but all I saw in my mind’s eye was a child’s face, mutilated and screaming. Perhaps painting was not in the cards for today.

A dull headache poked its way behind my eyes-a foreshadowing of the near-incessant headache I would have by the end of the month-and I sighed, giving up. I plopped my paintbrush, dry and useless, down on my easel and stood. Tea. It was time for tea.

As I walked from my studio into the living room, I could hear Fredricka moving around upstairs, doing something or other in the second-floor bedrooms. I knew all the doors were closed along that hallway (What will we ever do with a five-bedroom house, Margaret? Hal had asked me when we reviewed the listing. We’ll have guests, I had responded, a rare moment of prescience for me), but I could still hear noises from within, different from the usual disturbances that arose from behind those closed doors. Jostling and rustling, the changing of linens. The scraping of furniture across the floor in one room, then a light crash coming from another. Fredricka was lively today.

September had an effect on Fredricka. She became busier, more chaotic. She was nervous. She didn’t like September, she told me once. She had seen more than a hundred Septembers, so she ought to know.

For her part, Fredricka expelled her September energy through cleaning, stacking things, and rearranging furniture in nonsensical ways. None of these chores were necessary, but I understood her intentions. One has to control something in the face of the great uncontrollable. I left her alone.

Fredricka usually made the tea, but it seemed like it would be my responsibility today. A frown crept onto my face, and I reminded myself a bit of a spoiled child. I chastised myself for my entitlement. Making tea, after all, wasn’t particularly burdensome, and it was a bit of good fortune to have Fredricka around at all, considering we hadn’t hired her. She had come with the house, in a manner of speaking. Still, one gets used to routines. As I rounded the corner out of the living room and into the foyer, I tried to remember where we kept the tea bags. Fredricka might have moved them. She liked to move things in September, and not because she wanted to be helpful. For all I knew, they had been shoved behind the toilet.

Lost in my thoughts, I was startled to hear a voice behind me.

“Tea, ma’am?” Fredricka asked. Apparently, she hadn’t been too distracted to make it, after all.

Despite my surprise upon learning that Fredricka was a nonnegotiable fixture of the house, I had come to realize that I enjoyed her presence. She was reasonably benevolent, or at least as benevolent as anything in the house could be. Still, the sight of her was always a shock to the system. Fredricka was a tall woman, and grand, in a way, as the house itself, with so much of her walled off and expressionless, unwilling to open and allow a peek of what lay inside. And of course, there was that gash on her head, gaping open like a split pumpkin, where the axe had sunk in over a hundred years ago. The wound began at the top of her forehead and stretched down through her right eyebrow. Her eye was sunken in as a result, pupil drifting, not quite right anymore. That took a while to get used to looking at.

I smiled at her. “I can handle it if you’re busy.”

“No trouble at all, ma’am.” Fredricka drifted down the hallway that ran parallel to the stairs and led into the kitchen, her long smock fluttering behind her. I followed.

The kitchen was the brightest room in the house, surrounded with windows displaying the greenery outside, which was just now yielding leaves tinged with yellows and reds. It had been one of the biggest draws of the house for me, with two large ovens, a glimmering white sink, and rows of ornate cabinetry (original wood, mind you). It turned out to be comparatively peaceful in here, and I usually ate my meals at the kitchen table instead of in the grand dining room just a few feet away. For some reason, the blood never made it into the kitchen, so this room would be a particular haven as September raged on. A true blessing, that was; seeing blood staining those pristine surfaces, however temporarily, would have broken my heart. I’d grown used to seeing carnage inches from my food (Fredricka prepared most of the meals, after all), but one must draw a line somewhere.

Fredricka busied herself with the kettle, filling it with water and placing it on the stove. Not wanting to stand like a statue waiting for Fredricka to serve me, I walked over to the basement door just off the kitchen to check the wooden boards nailed into the doorframe. I had replaced them recently, but I tugged on each beam all the same, testing the strength. Four of them were firm, but one wiggled a little. I inspected the nails-just as I thought, coming loose. In the year since the boards had gone up, I found that the nails did that from time to time. Checking the boards was essential. I made a mental note that the beam would need to be replaced soon. Not urgent, but best to act on these things sooner rather than later. I gripped the doorknob and gave it a tug. The door remained closed, held tight by the boards. I traced my finger over the small crack-a recent addition-that snaked down from the top of the door nearly midway to the doorknob, sharp but not large enough to threaten the integrity of the wood. Everything, for the most part, was as it should have been.

Turning back into the kitchen, I noticed that Elias had materialized next to the stove. I sighed. Elias could be a bit of a bother.

Elias was nine or ten. I could never remember. Whatever his age was, he was scrawny, with a smattering of unruly dark hair on his head. He always looked the same-gaunt and empty, his dirty white cotton shirt draping over dark shorts, and one sad knee sock dangling by his ankle. He stared at me with milky eyes and a sullen face. He didn’t have any visible wounds like Fredricka, but could somehow be just as eerie, if not more. I couldn’t interact with Elias the way I could with Fredricka, although God knows I’d tried: I tried asking him questions, telling him to tap his foot once for yes and twice for no; I tried asking him to move the planchette on a Ouija board; I even tried making outlandish statements about World War II just to get a rise out of him. Nothing. So I hate to say it, but I started treating him like a plant, narrating my life out loud to him with no expectation of him responding or even hearing. It looks like rain today, Elias. Oh, Elias, seems like the mail is running late. Not that we’re expecting anything but bills, anyway. For his part, Elias just stared.

“Can I make you something to eat, ma’am?” Fredricka asked, busying herself around Elias as if he were not there. Elias and Fredricka had nothing to do with each other and I had never seen them interact. I had started to assume Fredricka didn’t even see Elias until one day she referred to him as “that boy.” No clues regarding Elias’ perceptions of Fredricka were ever available, seeing as he never spoke, only howled periodically.

“Some toast, perhaps?” I responded. I moved to the pantry to retrieve the bread before Fredricka could get to it. We had an electric toaster, but Fredricka’s ability to use technology popularized after her death was sporadic at best. I tried to teach her about the toaster and even had her successfully use it once, but her preference was to roast the bread on a toasting fork over a fire, like she used to do. It was muscle memory for her; she just did what she was always used to doing. I understood and even empathized (aren’t we all creatures of habit in the end?) but the process took forever and I was hungry.

“I think we still have some strawberry jam.” I motioned to the fridge. This would give Fredricka something to do. After months and months of trying to convince Fredricka that she had no obligation to be our housekeeper and was free to do whatever she wanted on this earth, I learned that all Fredricka seemed to be capable of doing was work, and all she wanted from me was to be given things to do. All right, then.

Elias watched me with those unblinking eyes as I retrieved the bread from the pantry and a plate from the cupboard. He was like the Mona Lisa, eyes following me about the room, expression unreadable. It had initially been unsettling, but one grows used to unsettling things.

Fredricka rummaged around in the fridge. “We do have strawberry jam, ma’am,” Fredricka said. “Or, if ma’am prefers, we also have blackberry.”

“Blackberry sounds good, actually.” I turned with my bread, and walked towards the toaster. Elias was standing directly in front of it, empty eyes leering into mine. This was going to be a problem.

Comments are closed.