Synopsis:

Synopsis:

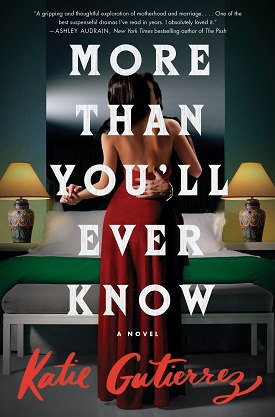

The dance becomes an affair, which becomes a marriage, which becomes a murder. Which becomes a pact.

In 1985, Lore Rivera marries Andres Russo in Mexico City, Mexico, even though she is already married to Fabian Rivera, resides with him in Laredo, Texas, and they have twin sons. Through her career as an international banker, Lore splits her time between two countries and two families . . . until the truth is revealed and one husband is arrested for murdering the other.

In 2017, while trawling the internet for the latest, most sensational news reports, struggling true-crime writer Cassie Bowman encounters an article detailing that tragic case. Cassie is immediately intrigued by what is not explored, the questions left unanswered. Why would a woman — a mother — risk everything for a secret double marriage? Cassie sees an opportunity to write the story that will finally launch her career. She’ll track Lore down and capture the full picture — all of the choices and deceptions that led to disaster.

But the more time Cassie spends with Lore, the more Cassie questions the facts surrounding the murder itself. Her determination to uncover the truth threatens to derail Lore’s now quiet life . . . and expose the many secrets that both Lore and Cassie are hiding.

Told through alternating timelines, More Than You’ll Ever Know is a mystery and family drama. Through a window into the hearts of two very different women, debut novelist Katie Gutierrez explores the conflicting demands of marriage and motherhood, and the impossibility of ever truly knowing someone . . . especially someone we love.

Review:

Author Katie Gutierrez was born and raised in Laredo, Texas, and grew up reading Nancy Drew, then “Fear Street” and, eventually, her mother’s Patricia Cornwell novels before earning an MFA from Texas State University. Her writing has appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, The Washington Post, Time, Longreads, Texas Monthly, and other periodicals. She now lives in San Antonio with her husband and their two children. More Than You’ll Ever Know is her first published novel.

Gutierrez stumbled upon the initial idea for the book while a student in about 2011. She happened upon the story of a man who had been married for thirty years, but led a double life. Two weeks after his wife’s death, he married another woman with whom, it turned out, he’d long had a separate family living twenty miles away. He had fathered two children with each of his wives, all of whom attended the same school but at different times. He even bought each of his wives the same model and color car. “I’ve always been fascinated with the ways that we compartmentalize ourselves, the ways that we change depending on who we’re with. I wanted to explore compartmentalization from the perspective of a woman living a double life,” Gutierrez recounts. “I feel like women are especially forced to compartmentalize themselves. I wanted to take that concept . . . to an extreme.”

Years later, the concept of a story about a woman leading a double life was still in the back of her mind when Gutierrez got interested in true crime after listening to the first season of the popular podcast “Serial.” That “pushed me over the edge,” and she next began watching documentaries about crimes, only to discover that they focused almost exclusively on female victims. More specifically, white women, even though eighty percent of homicide victims are men. And when women are murdered, the killer is most often a man with whom she was in an intimate relationship. Gutierrez came to the conclusion that such depictions create a false sense of danger for women, when “the most dangerous place for women is often in their homes.” But true crime is undeniably popular and Gutierrez theorizes that is because “there’s part of us that just has that dark curiosity. It’s like not being able to look away from a car wreck. We are drawn to things that we don’t understand and can’t comprehend.”

As the story opens in 2017, Cassie Bowman is trying to eke out a living as a true crime writer. Growing up in Enid, Oklahoma, she watched “Dateline” with her mother and checked true crime books out of the library, reading In Cold Blood and Helter Skelter at an early age. By the time she was in high school, she was obsessed — determined to become a journalist and write the kind of books she grew up reading. “Books that looked at the ugliest parts of humanity and asked: How did it come to this?” So far, she works fifteen hours per week earning thirteen dollars per hour writing blog posts for a television network that broadcasts low-budget true crime productions. It is Cassie’s job to find novel, gruesome crimes and write posts about them for an insatiable audience. She lives in Austin, Texas, with her fiancé, Duke, who owns and operates a food truck, and encourages Cassie to pursue freelance work on other topics because he finds true crime “macabre.” Cassie is tiring of her pursuits, feeling “like a forager of other people’s tragedies, . . .” she relates in the first-person narrative through which Gutierrez tells her story. “It was hard to be proud of this kind of work.” Duke grew up on a dairy farm with a large, loving family whose members have embraced Cassie and are eager to help plan and host their upcoming wedding. Cassie has never told Duke the truth about her own family, which is why she can never take calls from her younger brother, Andrew, in his presence. “There was too much he didn’t know. Too much to risk by telling him.”

A Google alert leads Cassie to a story in the Laredo Morning Times about Dolores and Fabian Rivera, and Cassie is drawn to the accompanying photographs. One, taken in 1978, shows the couple with their twin boys, Gabriel and Mateo, and was taken at a ribbon-cutting event. The second photo is of Dolores standing next to Andres Russo with her hand on the shoulder of a teenage girl, and was taken in 1984. The article reveals that Dolores was the girl’s stepmother, and Penelope Russo painfully recollects being deceoved by Dolores. The headline? “Her Secret LIves: How One Woman’s Double Marriage Led to the Murder of an Innocent Man.” Cassie is hooked. “I had to know more.” Pondering the sheer effort is would take to lead a double life, Cassie has to know why Dolores — a mother — would do such a thing. Her interest is in no small part fueled, as Gutierrez details incrementally, by her own family history. Cassie’s mother, a third grade teacher, died tragically just as Andrew came into Cassie’s life. That fact that Dolores refused to participate in an interview for the article does not deter Cassie. She begins researching the case, intent on finding out how Andres Russo ended up dead on August 2, 1986, after being involved with Dolores for three years and married to her for nearly a year. And why Fabian murdered him and is still incarcerated for the crime. She soon learns that Mateo owns a veterinary clinic in San Antonio and Gabriel is a high school basketball coach. And Dolores is still in their lives, plainly visible in family photographs posted on Facebook and Instagram. Cassie is flabbergasted at the notion that her sons were able to forgive Dolores . . . because Cassie has never been able to forgive her own mother.

In alternating chapters, Dolores’s story unfolds via a third-person narrative that begins in 1983 as she — “Lore” — commences another business trip to Mexico City. She loves being able to travel to the large city. “Nobody knows her. She could be anyone. She could become anyone.” Indeed. Gutierrez says Lore’s story had to be set in the past because today so much information is readily available online tha a double life would be much harder to pull off successfully. Additionally, it “created the opportunity to explore truth in a different way — what if the events known to have happened didn’t actually happen that way, or what if there was a deeper story behind them?” Lore meets Andres during a recession when she and Fabian are extremely stressed because Fabian is desperately trying to keep his business afloat even as the peso’s devaluation continues. Lore’s job in international banking is secure, but Lore opened a store selling custom doors five years earlier. With people struggling just to hold onto their homes, and constuction and remodeling projects stalled, the market for doors has shrunk dramatically. The pressure is impacting their marriage. Gutierrez, who grew up in Laredo, “a border town,” depicts Fabian’s intense pain and disappointment about failing for the first time. Even though it is not his fault, “in Mexican culture, there’s that element of machismo, and expectation that men will be the providers.” If Fabian’s store goes out of business, Lore will be the primary breadwinner. Meanwhile, her parents are experiencing the same consternation about their own business, and Lore and her siblings learn her parents have made horrendous choices, leading them to need financial assistance from their grown children in order to survive.

Mexico City provides Lore a respite from her responsibilities. She is invited to the wedding of the daughter of a Mexican entrepreneur and bank customer. It’s an excellent opportunity to network, and it is at the reception dinner that she meets Andres — the bride’s professor and advisor at the university. Lore is a beautiful thirty-two-year-old woman and the way Andres looks at her is electrifying. She does not tell him that she is married and has two sons at home. “And it’s only a dance, after all.” But thinking back on what happened years later, Lore will remember that moment as when she made her choice.

Cassie’s pursuit of her story unfolds as, in alternating and thoroughly grossing chapters, Lore and Andres fall in love in 1983, and Lore’s deception has escalating consequences. Her frequent business trips make it possible for her to spend time with Andres, who teaches and parents his daughter. Lore actively conceals the truth about her life from Andres, arranging to receive his telephone calls at the bank at specified times, for instance. When Andres asks her if she wants childen, she tells him, “I’m not sure,” conflating the inquiry in her mind to “Do you want more children?” so that she can delude herself into believing that she is being honest. Her relationship with Andres is exciting — romantic and dangerous — and something that Lore possesses just for herself. Gutierrez convinclingly and compassionately portrays Lore as a woman who truly loves Fabian and her children, but for whom her life with them is not enough — it’s both too confining and requires too much of her. Even motherhood did not fulfill Lore. “Motherhood is supposed to be quiet and pretty. But motherhood is not pretty. Motherhood has teeth.” She went back to work over Fabian’s objections. Gutierrez also draws readers into Fabian’s plight. Back at home in Laredo, striving to provide for his family, he has no idea that his wife’s business trips are actually trysts.

Cassie locates Lore, who agrees to be interviewed but not about the murder of Andres. Cassie also speaks with Lore’s sons, Penelope, and others who can provide background and context to the story she plans to write. With Lore, Gutierrez strove to create “a character who is acting in an ostensibly amoral way and portray her in a way that very quickly makes her actions understandable.” She succeeds. Like Cassie, readers are drawn to Lore, realting to and empathizing with her desires and dreams. Like Lore, Cassie is passionate and driven. Her ambition connected her with the woman to whom she reveals details about her own family history that she has never been able to tell Duke, blurring the line that separates her professional pursuit of the truth with her personal needs. Lore cleverly turns the tables on Cassie, drawing information from her as they spend hours talking. As her work on the story continues, Cassie’s perspective on her own family evolves as her relationship with Duke begins to falter, particularly when Andrew needs her help and Duke becomes privvy to the aspects of Cassie’s past she hid from him.

For every story told out loud, there is the story we only tell ourselves. And behind that — somewhere, often out of reach — is the truth. The trick is telling them apart.

Once Lore’s story advances to 2017, it becomes a carefully curated first-person account that seems mostly straight-forward and honest, but it is always clear that to see Lore as a victim is a mistake. She manipulates Cassie, telling her just enough to satisfy her, but not everything. And there are several junctures at which Cassie discovers that she has been fooled by Lore, who agreed to participate in the intervews for her own purpose, as Gutierrez skillfully reveals gradually. Is it a performance for Lore or is she a sixty-seven-year-old woman with regrets who has spent many years trying to right the wrongs she committed?She acknowledges that she loves reliving that period in her life. “And the truth is, I had always been a hedonist. A slave to the pleasures of the moment. Wasn’t that how everything had started? Because, in a time of deprivation, Andres had given me his hand? How could I have said no? To the dance, to the wine?”

Cassie’s investigation reveals inconsistencies in the details related by witnesses during police interviews and the evidence uncovered during the criminal investigation. Cassie comes to believe that the wrong person is serving time for killing Andres. But if Fabian did not kill him, who did? Is Fabian covering for someone? The book’s pace accelerates as Cassie closes in on the truth and finds herself in danger. But Gutierrez delivers more than just a murder mystery. She also examines, through Cassie’s conflict with Duke, the — perhaps unintended — consequences of true crime stories. Despite her agreement with Lore not to discuss the murder, Cassie cannot ignore her misgivings about Fabian’s conviction, even though he confessed to killing Andres. Cassies tries to convince Duke that revealing the truth is a means of honoring the decedent, “a way of saying their life mattered.” But Duke reminds her that she only has Lore’s permission to write about her double life. She has not obtained permission from anyone else connected to Lore or Andres’s death to write about it, and her unwilingness to respect boundaries has the potential to bring about devastating results. She envisions uncovering the truth as a duty. But the truth always comes at a cost, as Gutierrez deftly demonstrates.

More Than You’ll Ever Know is a inventive meditation on the demands of marriage and motherhood, the sacrifices they require from women, and the way society views women who refuse to settle for less than they want and feel they deserve. It is also an absorbing look at ambition and the power of investigative journalism, as well as forgiveness. Is there any action that is truly unforgivable? Or is the capacity for undertanding and empathy so vast that the most unimaginably hurtful betrayal can be forgiven in order to preserve one’s family?

But at the core of the story is that nagging question: Why? Why did Lore risk the family she had already created with Fabian in order to pursue a new one with Andres? Did she really think that she could get away with it? Didn’t she understand that it was a catastrophe waiting to unfold and that when her duplicity was revealed, the people she loved would be broken by her betrayal? Lore tells Cassie, “I wasnted to be known. I wanted to know myself. That’s what it was all about. And I ended up alone.” Is Lore’s explanation worthy of belief? And in the end, is Cassie’s dogged pursuit of the truth worth what it costs her? Finding out the answers to those questions, and pondering the issues Gutierrez broaches in More Than You’ll Ever Know is a delightfully entertaining and engrossing experience. More Than You’ll Ever Know is so tautly crafted, her characters so fully developed and fascinating, it is hard to believe it is a debut work of fiction.

Excerpt from More Than You’ll Ever Know

Cassie, 2017

By the time I read about Lore Rivera, my mother had been dead for a dozen years. Dead, but not gone. She was like my shadow, angling dark and long in the right light, inescapable and untouchable.

Everyone had loved my mother. She was a third-grade teacher who’d once told our class that history was written by those who had power and wanted to keep it. “So, when you read your textbooks, ask yourself who is telling the story — and what they have to gain by your believing it.” My classmates had looked at me then, awed by my mother’s educational subterfuge, and I’d smiled, proud she was mine, that I had come from her.

Every Friday night, she and I curled up together on the nubby tweed couch to watch Dateline. Sometimes our fingers brushed as we worked the matted tassels of our favorite blue blanket, and we giggled softly, as if catching each other in the act of something private. Then we’d wait for Stone Phillips, with his strong jaw and serious eyes, to reveal the endless ways one human being can harm another.

This was the midnineties in Enid, Oklahoma, still some time before my ninth birthday. My life was still ordinary. I hadn’t yet learned that ordinary could be precious. So I got my thrills from watching the Dateline camera pan over photos of smiling blond women riding bikes and cutting wedding cakes, oblivious to their own tragic ends. I couldn’t help but see myself in them, or see myself the way the camera might see me, a dead girl still living. I breathed in my mother’s scent of snuck cigarettes and chalk dust as she pulled me against her side, and maybe that was the pleasure that started it all — from that nubby tweed couch, I explored an otherworld of danger without ever leaving the safety of my mother’s warmth, thrilled in the closeness of the wolf’s breath against a home made of brick.

Except it turns out brick walls don’t matter when the wolf lives inside.

Later, once I stopped watching Dateline with my mother, once I stopped doing anything at all with her, I checked true crime books out of the Enid Public Library three or four at a time, slipping them into my backpack like contraband. I devoured In Cold Blood and Helter Skelter the way I imagined boys my age looked at porn, all that furtive grasping under covers. I was grasping for something, too. Some kind of dark knowledge, understanding. I slid my hands over their plastic covers, greased with fingerprints like mine. I read the other names on the borrowing cards—Jennifer, Nicole, Emily—and wondered if they, too, read about serial killers beneath the golden dome of their covers, grateful for something more frightening than their father’s voice bleeding through the walls.

In high school, my clandestine obsession with true crime crystallized into clear goals: First, and most important, leave Enid, Oklahoma. Go to college. Become a journalist. Write the kind of books I had consumed, and that had consumed me, for so many years. Books that looked at the ugliest parts of humanity and asked: How did it come to this?

The year Lore Rivera entered my life, I’d finally landed pieces in Vice and Texas Monthly, but my biggest coup as an aspiring true crime writer was a part-time blogging gig for H2O, a television network whose market research had made it pivot from low-budget romance movies to true crime. Women, it seemed, had tired of watching pretty white couples fall in love among ice-skating rinks and hay bales. Instead, they wanted to know how many times you’d have to stab someone with that ice-skating blade in order to kill them, and whether bodies in those small farming towns ever stayed buried. And their appetite was voracious—not only did they want the “full-time crime” the network provided; they wanted a blog that would round up “the most interesting murders on the internet.” No humdrum shooting would do. They wanted novelty. That’s where I came in.

For fifteen hours a week and thirteen dollars an hour, I scoured the Web for killings that would make a jaded audience stop and click. I read national and local newspapers, scrolled through true crime message boards and subreddits, burrowed my way through 4chan threads like a spelunker of human grime. I created a set of Google alerts—terms like “murder,” “dismemberment,” “kidnapping,” and “contract kill”—and every morning my inbox replenished like an hourglass overturned.

The best-performing murders were outlandishly gruesome with an element of either brilliance or ineptitude (the latter being far more typical). They also tended to have one thing in common: women ended up dead. Though only a quarter of all murder victims are women, when women are murdered, it’s almost always by a man, and when men kill women instead of other men, well, that’s when shit gets creative. Hacksaws and living burials and mysterious disappearances from tiny Cessnas. On a blog like ours, that’s what sold.

That Friday morning, my top post was about a Florida man who’d bashed in his ex’s head with a power tool after she’d caught him with another man. Then he’d partially dissolved her limbs in acid before chopping the rest into small enough pieces to fit into a five-gallon fishing bucket, which he’d taken to a swamp to feed to the alligators—except the gators were more enticed by the man’s living limbs. He’d been forced to call 911, too badly mauled to dispose of the bucket’s grisly contents before emergency responders arrived. Most of the comments were some gleeful form of Karma’s a bitch!

I often wondered about my audience, most of them women, at least according to the market research. How did they interpret their pleasure at scrolling through the posts I curated? Did the human brush fires reduce their own miseries to matchstick flickers? Did the violence provide them with a language for their private suffering?

I wanted to think there was some of that, because more and more I felt like a forager of other people’s tragedies, grinning as I presented them like trophies to an invisible bloodthirsty crowd. The woman in that fishing bucket—she’d been someone once. Maybe her baby teeth were still tucked away in a drawer somewhere, the way my mother had saved mine in that old felt jewelry pouch I’d found after she died.

It was hard to be proud of this kind of work.

———-

I had one eye on the clock, counting down to when I needed to start packing for Fourth of July weekend with my fiancé’s family, when my email refreshed with a Google alert: “Her Secret Lives: How One Woman’s Double Marriage Led to the Murder of an Innocent Man.”

I was so accustomed to dead women that, for a moment, I thought I’d misread the headline. Then came the prick of curiosity, instant and sharp.

The story was from the Laredo Morning Times, a local newspaper for a city a few hours south of Austin, where I lived. I clicked on the link. My screen filled with the bold headline and two black-and-white family photos, divided by a dramatic stylized tear. In the first photo, captioned 1978, a man named Fabian Rivera and his wife, Dolores, held a pair of oversize scissors at some kind of ribbon-cutting event. Her curly black hair was feathered over each ear, earrings dangling to her jaw. She was laughing, her cheeks round, chin slightly tilted, as though she’d been about to look up at Fabian. She wore a harsh shoulder-padded skirt suit, and Fabian stared at the camera with a small twist of a smile at the corners of his lips and eyes. Beside them, two dark-haired boys, twins –captioned as Gabriel and Mateo Rivera — grinned, as if they were doing bunny ears behind their parents’ backs.

The other photo was taken in 1984. It was a studio portrait with a cheesy Christmas backdrop: glittering fist-size snowflakes suspended above the branches of a heavily ornamented pine. This time the same woman — Dolores — leaned into a different man, captioned as Andres Russo. He smiled broadly, his right arm around her shoulder. Dolores’s palm rested on the shoulder of a laughing teenage girl, who wore slouch socks and Dr. Martens with her plaid skirt. Beside her, a boy of eleven or twelve was wide-eyed behind dark-framed glasses.

Nothing in either photo suggested a crack in the couple’s intimacy — but then, my own parents had chopped onions and bell peppers side by side for fajita night right up until the very end. They’d held hands in the car, singing to the Eagles. On every anniversary, they retold the story of how they met: two nineteen-year-olds craving Baskin-Robbins on a rainy winter night. Fate.

The way things seemed meant nothing.

I took a sip of cold coffee and began to read.

Penelope Russo was 15 when she met Dolores Rivera, the woman who would become her stepmother — and change her life forever. It was December 1983, and they spent that first meeting decorating the Christmas tree in Penelope’s father Andres’s Mexico City apartment. The tree was small and artificial, because Penelope’s brother, Carlos, then 12, was allergic to the real ones. The whole endeavor took 20 minutes, and then they went to Churrería El Moro for hot chocolate and churros.

Even from the start, Penelope could understand her father’s infatuation with the new woman. Dolores was 33 years old, a successful international banker from Laredo who still had her job in the midst of the devastating peso devaluation. She was smart and magnetic, Penelope remembers, with sparkling brown eyes and a contagious laugh.

The memory, it is clear, comes at a painful price: to recall Dolores is to recall the pain of being deceived, the shock of trusting someone — loving someone — whose every word turned out to be a lie.

Already, my curiosity was mutating, growing limbs, sprouting new and reaching fingers. I imagined a part of my mother, left in me, quivering like a magnet sensing its opposite.

I had to know more.

The Laredo Morning Times didn’t have much of a presence on Twitter, but on Facebook, local readers tagged each other eagerly, whittling the degrees of separation between themselves and Dolores: someone’s aunt used to work with her; someone’s dad had asked her to go around in high school; wasn’t she the lady on that bank billboard on San Ber a few years back, the one close to the bridge? Pobrecitos los esposos, imagine! and Qué agüite, did they take away her kids? and No fkn way, that’s my neighbor! Always outside watering her jungle. About half the comments were in English, the other half in Spanglish or full Spanish, so that I had to open Google Translate to understand them.

Occasionally, obvious outsiders chimed in: a man with an American flag as a profile photo wondering whether Dolores was still fuckable, or a ruddy-cheeked white dude in a fisherman’s hat writing, Fucking Mexicans. Not one but two incels emerged from their semen-scented basements to say this was why women should be kept as sex slaves—it was the only way innocent men could protect themselves. To these comments, the women responded with variations on Go fuck yourself, pendejo, no one else will.

I wouldn’t exactly call it nuanced commentary.

When the front door creaked open, I was still sitting on the gray love seat that doubled as my office. “Shit,” I hissed, looking at the time. It was after four. My fiancé’s family farm was three and a half hours from Austin with no traffic — as if there was ever no traffic –and they were expecting us for dinner at eight. I hadn’t even started to pack.

“Hey, pretty lady,” Duke called, his initial grin fading when he took in my open laptop, my socked feet.

“Before you ask,” I said, meeting him at the door, “I’m not quite ready yet.” Duke was broad and sturdy, his skin silty with sweat, and he smelled like pit fire and honey when I kissed him.

Duke hated to be late. That was the thing about growing up on a dairy farm: if you don’t milk a cow or goat when you’re supposed to, she’ll wail and stomp in agony that you caused. So Duke had grown up doing what he was supposed to do when he was supposed to do it. I’d loved that at the beginning of our relationship, how he called and texted and came by exactly when he promised. But it didn’t leave a lot of room for error.

“Work,” I added, noticing the glimmer of irritation on his face.

“Oh.” Duke’s expression relaxed as he opened the fridge, making sure nothing would go bad while we were away. “The Antone’s retrospective? I’m excited about that one.”

Duke was highly supportive of my noncrime freelance work. To him my obsession was macabre, the way I could binge hour after hour of crime shows, from prestige documentaries to Forensic Files, depending on my mood; the stack of books on my nightstand with dark covers and long, bold lettering. The podcasts I listened to during my walks — once wandering eight miles around the lake because I had to hear just one more episode of Serial — and the message boards I returned to when I couldn’t sleep, my late-night tumble of rabbit holes. The folder on my desktop labeled “Interesting Crimes,” where I dropped articles and screenshots and early research. All of this in addition to working on the blog for fifteen hours a week.

But then, look where Duke came from. Parents who still held hands forty years later, who called on Sundays and sent dry-iced care packages of crème fraîche, goat milk yogurt, honey, and jams. Siblings constantly blowing up the group chat with photos and memes and personal news. Childhood memories of brushing horses’ flanks until they shone like water, and literally coming home when the dinner bell rang. Even after meeting his family, I’d sifted through his stories for hidden resentments, secret trauma, and found nothing. He was boyishly open, untainted. I loved this about him. But it meant he believed people were inherently good and didn’t like looking at evidence to the contrary. I never wanted to be surprised again, so I looked and looked until even my dreams were bloody.

“I filed the Antone’s piece last week,” I said. “No, I found this story about a woman — a mother — who was secretly married to two men at the same time back in the eighties. One of the husbands ended up murdering the other.”

Duke gave a half laugh, throwing out some ham on the verge of going slimy. “Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to get normal work updates from you.”

“Imagine how much effort it took to pull that off,” I continued, powering off my laptop. “And why, you know? What makes a woman, a mom, do something like that? Not that mothers always put their children first” — I should know — “or even that they should, but this is something else.”

“Yeah, it’s definitely weird. But, Cass — ” Duke jangled his keys, a nervous tic he never noticed.

I glanced up, on alert. “Yeah?”

He crossed the room to where I crouched, pulling my charger from the wall. “We’ve hardly seen each other lately. Can we take a break from work this weekend? Maybe leave the laptop behind and make it, like, a murder-free zone?”

I laughed, though my grip tightened on my charger. It was easy for him to suggest leaving work behind—it wasn’t like he could smoke the brisket for his food truck at the farm. And if Sal called with a problem over the weekend, he’d obviously answer. The food truck was his business. Crime was mine. Sort of.

But he was right. For weeks we’d only been catching each other in moments: a twenty-minute dinner break at the food park; the occasional mindless movie on Netflix; half-asleep sex that almost felt like a dream in the morning.

“Okay.” I exhaled as I set the charger down, already feeling strangely limbless. “Sure. Family time. No murder. Promise.”

———-

I-35 was, as expected, a parking lot. Duke bit back any accusations and asked me to text the group chat that they could start eating without us. In return, I resisted the near-constant urge to research Dolores Rivera on my phone. By the time the sky screamed with sunset, we were relaxed and holding hands, dreaming up honeymoon destinations — the food in Laos was supposed to be incredible, Duke said; I told him about an article I’d read about hiking glaciers in Iceland — drunk on possibility while ignoring every practicality, beginning with the fact that we had no money and hadn’t planned a damn thing for the wedding itself.

It was nearly nine when we reached the farm, 150 acres bordered by a four-rail white wooden fence, with a stone sign reading Murphy Family Farm, Est. 1985. Duke’s F-150 jolted and clanged on the rough gravel road as we passed the goat pen with its three-walled tin structure, where the goats slept on shelves at various heights like kids at summer camp. We passed the coop with three hundred laying hens and the cow pasture and stables and corral before finally approaching the shiny red milking barn and white metal store stocked with fresh milk and eggs, in-season vegetables, and the lavender soap and candles Duke’s mom, Caroline, made by hand. Just beyond was the farmhouse. Wraparound porch lit up bright, double swing and rocking chairs waiting for desultory after-dinner drinks. The wine went down easy here. And peacefully, too. I still wasn’t used to that.

Inside, we took off our shoes at the door, lining them up underneath the scratched and scarred entryway bench. The wide wooden planks were smooth underfoot, softened in places by faded rugs in shades of saffron and ocher. We followed the sound of laughter and conversation to the dining room, where everyone was sitting at the long farmhouse table that Duke’s grandfather had made by hand right before shipping off to World War II. The table was set with burlap place mats and hammered copper salt and pepper shakers, and there were several open bottles of wine, evidence of fresh bread and butter, but no dinner. They’d waited for us. Of course they had.

“Here you are!” said Caroline. The low light from the wooden chandelier caught the three silver earrings curling up each ear as she stood. She wore her blond hair short and spiky, and when she hugged me, I melted into her strong, solid body. She squeezed Duke, then turned to his father. “Alf, come help in the kitchen, will you?”

Alf was slighter than Caroline, softer spoken, with a silver handlebar mustache and a Cowboys cap he hung off a brass hook on the wall. “With pleasure,” he drawled.

“We told you guys not to wait!” Duke said.

His younger sister Allie rolled her eyes with a smile. “Like that was going to happen.”

Allie was twenty-five, petite, with neat, clean features — bright blue eyes above youthful freckled cheeks. Stephie was in her sophomore year at Northwestern and apparently in the middle of urging Kyle, the youngest, to apply for the following year so they could be in school together again.

Five minutes later, we were squeezed between Allie and Duke’s older brother, Dylan, cutting into herb-rubbed chicken that was somehow still tender and warm. Dylan bragged about Allie’s latest barrel racing stats. She accepted the praise matter-of-factly, adding, “They never saw us coming.” The conversation meandered comfortably. How’s the food truck, Duke — Hey, Cassie, did he ever tell you about the time — Can someone pass the potatoes — Mom, do we have any coffee milk this time — Did y’all remember to restock the shelves — When’s Millie due to calve?

Being here was like getting into bed at the end of a long day—warm, safe, comfortable. But I couldn’t help wondering how many Facebook comments had been added to the Dolores Rivera story since we’d left Austin. How many article shares? There was no way I was the only reporter who’d looked at the italicized line below the article — Dolores Rivera declined to be interviewed — and seen something else: an opportunity.

I’d felt it right away. An intimate story from the perspective of a rare female bigamist, whose crime led to murder? That was special. That could be big. Harper’s big. New Yorker big. In Cold Blood had started as a New Yorker series. One long-form true crime piece to launch my career. I was so fucking sick of the blog, of being broke, consulting my overdue-invoices spreadsheet every Friday afternoon, sending my “just following up” emails, hoping to strike the right tone of polite assertiveness that wouldn’t get me blackballed from the publication. If I didn’t get paid at least five hundred dollars by the time rent was due on Thursday, I’d have to tell Duke — again. He’d say we’d figure it out — again. Suggest — again — we open a joint account. Wouldn’t it be easier to pay all our bills from the same place? Less stressful? It probably was, for some people. And I wished I were one of them, I did, but the thought of combining our finances made me feel like burying myself alive.

“Cass?” Duke reached for my hand, teasing my marquise sapphire with his thumb. The ring had belonged to Duke’s grandmother, and I always felt in it the weight of a family’s history, its memories and unions. It made me feel like I belonged somewhere. “What do you think?” he asked, smiling.

“Sorry,” I said, sheepish. Everyone was looking at me. “What do I think about what?”

Duke’s jaw tightened. “Mom was just suggesting—”

“Offering!” Caroline waved her hands. “You can absolutely say no.”

“Offering,” Duke said, softening, “that we have the wedding here on the farm.”

It had been seven months since Duke proposed. The cold Ferris wheel seat at the Trail of Lights had trembled beneath us, hovering over trees illuminated in bright primary colors, and the city itself had sparkled against the dark sky. My chest ached with an old, tender memory. I’d cried as I said yes.

But the average cost of a wedding in this country was thirty-five thousand dollars. Who had that kind of money lying around or was willing to go into that much debt for one day? Even the dresses on sale at David’s Bridal, which I’d taken a tepid look at online, cost seven hundred bucks. And as soon as we decided on a location, they’d want a deposit, which we didn’t have. So, we’d been stuck.

Now here was Caroline, offering the perfect solution, which I couldn’t believe we hadn’t already considered. I could see it now, the neat rows of white chairs arranged before a trellised gazebo Alf would make by hand. Caroline would bake a tiered naked cake, its buttery sides dusted with powdered sugar. Duke and I would walk to the altar together, and I’d officially become a part of a family where everyone had grown up sleeping with their doors wide open, no shouting to stifle, nothing to fear.

“Yes,” I blurted. “Of course. I mean, right?” I said to Duke. “That’s perfect.”

Duke grinned. In the chandelier’s low light, his eyes were the color of maple syrup spread thin. “It is perfect.”

Caroline clapped, and Dylan went into the kitchen for the bottle of champagne Alf thought he remembered seeing in the back of the fridge.

My phone vibrated in my pocket. I froze midlaugh as Andrew’s face filled the screen. An old photo, his skin red-gold in the sunset at Great Salt Plains Lake. Though his legs were out of frame, I knew his jeans were rolled to the knees, his calves immersed in the clear shallow water. My heart seized at the happy way he was looking at the camera. At me.

I was suddenly aware of my own heartbeat, its guilty thuds, as I declined the call. Andrew. He’d come into my life right as my mother left it. He’d saved me that summer. From my grief, from myself. But I never knew what might be on the other end of his calls, which meant I could never answer in front of Duke. There was too much he didn’t know.

Too much to risk by telling him.

———-

It was almost midnight when we crawled into Duke’s old pine bed, my back to his chest, his hand on my hip. Sleep on the farm was usually like a hole I stumbled into in the dark, one moment tethered to the ground, the next falling. Gone.

But not tonight. Tonight, my thoughts kept flitting between Andrew and Dolores Rivera. If something was wrong, Andrew would have called again, I reassured myself. He would have texted me. And why was it that some people, like Duke, could hear about a woman who’d lived a complete double life that led to a murder, and simply move on, while others, like me, worried the threads of that story like yarn between fingers, scraping the skin raw?

Duke kissed the spot below my jaw that made me shiver. “I’m so happy we’re going to get married here,” he whispered.

“Me too,” I said, though my mind was still on Dolores, thinking about the buy-in you’d need for someone to believe you’re essentially alone in the world. What had Andres Russo’s family and friends thought of his wife, a woman with a foot in two countries? Who had gone to their wedding? Didn’t anyone wonder why she had no family in attendance, no friends?

My stomach lurched as I realized my own side of the aisle would be nearly as empty—everything, everyone I was missing creating its own gravity, impossible to ignore. The truth is it doesn’t take elaborate lies, only being with someone who doesn’t push to know the things you don’t want to reveal.

When Duke’s arm loosened around me in sleep, I pulled my phone off the charger and texted Andrew: Sorry I missed your call. Is everything okay?

The ellipsis appeared. Disappeared. Appeared again, followed by: Yeah.

I stared at the word until my eyes burned. Yeah. Simple, curt. He may as well have written Fuck you.

Okay, I responded. I’ll call you soon so we can catch up. I hesitated, remembering the warmth of his skin on mine so long ago. I miss you.

This time, nothing appeared after the ellipsis. My heart was a comet trailing fire in my chest.

I put the phone away and closed my eyes, but I was viciously awake. Carefully, I edged out of bed, plunging my hand into my duffel bag and rummaging below jeans and tops and underwear until I felt the familiar comfort of cold steel. Then I pulled out the laptop I’d promised Duke I would leave behind.

I settled cross-legged onto the floor, my back against the bed. The computer chimed softly when I turned it on. Duke shifted as the room lightened with electronic blue. I held my breath, curved over the screen, dimming it with my body. After a moment, the covers stilled. His breathing deepened.

Exhaling, I pulled up the Laredo Morning Times piece again. Dolores Rivera and Andres Russo had been married for just under a year, together for nearly three, when Russo’s body was found at the Hotel Botanica, a motor inn in Laredo, on August 2, 1986. It wasn’t long before the police discovered that Russo, who lived in Mexico City, was in town to visit his wife, Dolores Rivera. (So why was he staying at a motel instead of with Dolores? Where did he think she lived?) He was believed to have been “shot the evening before, on a day temperatures soared to a record-breaking 117 degrees before a much-needed rain cooled things off.”

The detectives at the time, Manuel Zamora and Ben Cortez, had questioned both Dolores and Fabian, but if she’d been a suspect initially (which of course she was), soon Fabian eclipsed her as a person of interest: a clerk had seen him leaving the motel around 10 P.M. on August 1, which turned out to fit squarely within the window of Russo’s time of death.

Fabian was no criminal mastermind — he’d also left a partial print in Russo’s room, and the slug lodged in Russo’s body was later matched to ammunition found in Fabian and Dolores’s home, ammunition used for the Ruger Mark II .22 caliber pistol Fabian claimed to have lost. The bullet had entered from the right side of Russo’s chest, tearing through his eighth rib to lodge within the soft tissue of his lateral right back. It fractured the rib and punctured the lower right lung. Russo had drowned in thirteen and a half ounces of his own blood.

The reporter traded gleefully in these details, though I’d been writing my own grotesqueries long enough to know what they masked: a lack of any real insight into the crime. Not only the murder, but the crime that had led to the murder — Dolores’s double marriage. Instead, there were quotes from Dolores’s former stepdaughter, Penelope Russo, calling her a monster who’d used their family and thrown them away, like trash. As a treat, the reporter indulged in a little armchair pathologizing, questioning whether Dolores was a psychopath or merely a narcissist, and maybe that shouldn’t have pissed me off, but it did — he was one step away from calling her crazy, that one word with the power to dismiss every aspect of women’s emotional and intellectual lives, our motivations and desires. Which, especially in their absence, were the most interesting parts of this story.

The first search results for Dolores Rivera’s name paired with Laredo were the article and its various comment threads. The paper’s online archives only went as far back as 2005, with similar results for all other major Texas cities. Whatever had been written about her at the time of the murder was relegated to a reference library somewhere.

After the Laredo Morning Times piece, there was a retirement announcement from five years ago — astonishingly, from the same bank where Dolores had worked in the eighties. It featured what I assumed was a semi-updated headshot: Dolores with a thick, straight collar-length bob, her hair mostly still dark, wearing red lipstick and a matching silk shirt. Her brown eyes were warm, competent, and amused. She was still an attractive woman. Had she been in other serious relationships since the murder? Who would be able to trust her after what she’d done?

After the retirement announcement and an outdated LinkedIn page, the results lost accuracy, linking to Spanish GoFundMes and college volleyball game write-ups. I searched for her on social media with no results. Then I reopened the Laredo Morning Times article. There were Dolores and Fabian, with their hands on the oversize scissors.

And their sons.

Mateo and Gabriel Rivera must be in their midforties now. I started with Mateo: easy. He owned a veterinary clinic in San Antonio and reminded me of the serious runners at the lake, tall and greyhound-lean, with silvering dark hair. Mateo didn’t have any personal social media, but the clinic maintained an enthusiastic Instagram account. In photos with animals, Mateo was almost always smiling: caught midlaugh between three lion-headed pit bulls at an outdoor adoption event, or beaming as he held a drooping pug puppy with an IV taped to its arm: Clyde is off oxygen! But with other people Mateo seemed serious, almost awkward—too much space between him and the person beside him in a group shot, a hand hovering instead of resting on a shoulder.

Gabriel, on the other hand, was a seasoned and prolific Facebook poster. He was a bull-necked high school basketball coach, with a black goatee and a gold class ring on one hand, a wedding band on the other. In clips of his games, he flung out his arms, eyes cast to the rafters, when players missed a free throw. With the volume off, the gesture looked almost rapturous. I could imagine his voice in the locker room afterward, though, bouncing off the dull, slatted metal doors: Is this what we practice for? To lose the points that are handed to us? Something about him — the predatory way he paced by the bench, the expansiveness of his gestures — made him seem like a yeller.

Then again, there were the photos of him with his sons. I stared at one in particular for a long time. Joseph and Michael were three and five. Gabriel was kneeling in patchy grass, his arms around them, the sons each wearing a neon green Velcro mitt. Over the skinny shoulder of the older one, Gabriel’s eyes were closed. His smile was painfully tender. His wife, Brenda, had posted the photo tagging Gabriel, with the caption Mi corazón. For some reason, I took a screenshot.

Gabriel and Brenda, a “leadership consultant,” whatever that meant, still lived in Laredo. They liked fried sushi rolls stuffed with cream cheese and jalapeños and had once won a radio contest to eat barbecue with the Eli Young Band at Rudy’s and recently finished construction on a fortresslike stucco house in a subdivision called Alexander Estates. According to Google Maps, the neighborhood was right beside the high school where Gabriel coached. In a video Gabriel posted, he zoomed in on the edge of the cement driveway, which bore four handprints in a row, from large to tiny.

I scrolled through hundreds of photos on Facebook and Instagram, watching Gabriel’s and Brenda’s lives flow backward until they diverged and their future together was only one possibility out of millions. What a foolhardy thing, splaying yourself out like this for anyone to see, evidence of that very human desire to be known. Well, here I was, coming to know them like a tracker comes to know an animal through its scuffs in the dirt, its scent on the wind.

Startled, I realized Duke was no longer snoring. The room was silent. For a moment I swore I could feel his gaze raking over my back as I did exactly what I’d promised not to do on this trip. I turned around slowly, preparing for the shake of his head, the disappointed slant of his mouth. But he was asleep. Or at least pretending to be.

I scrolled forward again through Gabriel’s photos, quick, deliberate. And there she was — Dolores Rivera. Rarely in the foreground and yet seemingly always there, part of the scaffolding of Gabriel’s and Brenda’s lives. She was proud in a gold gown in the first pew of a church for their wedding. Her hands covered in mushy orange baby food as she fed Joseph at a high chair two years ago. Standing at a basketball game, palms cupped into a megaphone around her mouth. Picking up strewn wrapping paper at a kid’s birthday party. That photo, in particular, made my breath catch. It reminded me of a day I tried not to think about, one that had defined my entire existence.

The point was this: despite the wreckage her choices left behind, Dolores hadn’t lost her sons.

Somehow, it seemed they’d been able to forgive her. How had they done that? How had she earned it?

I’d never been able to forgive my own mother. What would she think of a woman like Dolores, someone who’d wanted more than the life she had, or a different life, and spun one into existence?

Again, I looked at the brief, italicized sentence right below the article: Dolores Rivera declined to be interviewed.

Well, now that the story was out, maybe she would be ready to tell her side.

Comments are closed.