I am delighted to welcome LeAnn Neil Reilly back to Colloquium.

I am delighted to welcome LeAnn Neil Reilly back to Colloquium.

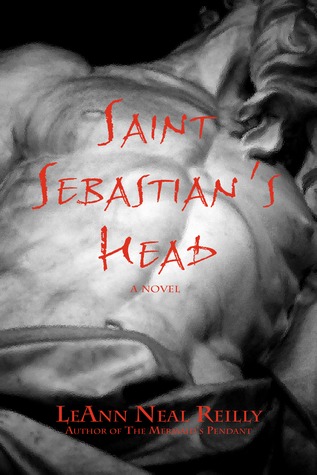

LeAnn is the author of The Mermaid’s Pendant, her re-imagined version of The Little Mermaid, as well as Saint Sebastian’s Head, a much darker, more haunting tale about childhood incest and abuse, and survivor guilt.

Weeble’s childhood was so characterized by pain and trauma that she hides the details from everyone — even herself. When she was ten years old, she and classmate Lauren Case became friends. Lauren’s life was far different from Weeble’s, but they shared a love of reading. Lauren, Grandma Nan, who was raising her, and their lovely home provided a safe refuge for Weeble from her drinking and drug-using parents who paid little attention to her or her little sister, Annie. Although Weeble tried to protect both Annie and Lauren, she was unable to stop the sinister and malevolent forces that ripped apart their lives. Now, four years after graduating from college, Weeble has a chance at real happiness and to be loved just as she is — if only she can acknowledge the truth about the past and forgive herself.

Counterbalancing Darkness and Light

In writing Saint Sebastian’s Head, I chose to tell the story in the first-person against my initial inclination. That’s because I think that first-person narratives can be very limiting and really require a strong voice to make them work. I actually wrote about a third of the novel in the third-person viewpoint. Yet Weeble insisted upon telling her story. By then, I knew that this would be a grittier, starker tale than The Mermaid’s Pendant, my debut novel. I didn’t want it to be overwhelmingly bleak, though, and I considered how I could balance the narrative’s inherent darkness with light.

But how? Around the time I was pondering how to do this, I saw an art exhibit by Brazilian artist Ana Maria Pacheco titled Dark Night of the Soul. Pacheco’s installation featured larger-than-life wooden sculptures with St. Sebastian as the focus. St. Sebastian was a third-century Roman soldier who was slated for execution not once, but twice, for his vocal Christian beliefs. In the first attempt, in which archers riddled his body with arrows, St. Sebastian was left for dead. Before he died, however, St. Irene found him and nursed him back to health. Instead of fleeing from Rome to safety, St. Sebastian returned to the city where the emperor found him again. This time, Diocletian had him beaten to death. As an example of Christian heroism, St. Sebastian became one of the most revered subjects of artists from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, depicted almost as often as Jesus and Mary.

According to the introduction at the Danforth Museum where I saw the exhibit, “Dark Night of the Soul was inspired . . . by the writings of the Spanish mystic St. John of the Cross, to suggest a struggle deep within one’s self as opposed to actual martyrdom.” But Pacheco clearly wanted to suggest more than an internal spiritual struggle. The exhibit, dark and ominous, strongly affected me — I became, through my interaction with the sculptures, complicit in the hooded saint’s execution. It was eerie and chilling. But not the ultimate effect I wanted for Weeble’s story.

What if, I wondered, Weeble met a man who created art that was supposed to lift the viewer using light? What kind of art would satisfy that need? The answers were as close as my friendship with Michele Gutlove, whose glass artistry I’ve admired for more than a decade.

Glass art was the spiritual medium that I needed to counterbalance the darkness of Weeble’s tale. And St. Sebastian shows the challenges and the potential benefits of facing the darkness in her life.

Michele suggested that my artist, Tom Paul, create his exhibit, The Soul Illuminated, using pâte de verre. Some examples of this glass-making technique can be found here or here. The pâte de verre bust in the photo (right) reminds me of Tom Paul’s work. Michele graciously provided me with resources to research this technique and answered questions about Tom Paul’s possible education and training. In a word, she was indispensable, although it should go without saying that any mistakes regarding glassmaking that are in my novel are mine alone.

Michele suggested that my artist, Tom Paul, create his exhibit, The Soul Illuminated, using pâte de verre. Some examples of this glass-making technique can be found here or here. The pâte de verre bust in the photo (right) reminds me of Tom Paul’s work. Michele graciously provided me with resources to research this technique and answered questions about Tom Paul’s possible education and training. In a word, she was indispensable, although it should go without saying that any mistakes regarding glassmaking that are in my novel are mine alone.

Even though Weeble’s story is difficult and disturbing, I hope that, like Tom Paul, I’ve found a way to show that light and love can reach us wherever we are, triumphing over the most egregious harm as well as everyday degradations.

Meet LeAnn

LeAnn Neal Reilly graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a master’s degree in professional writing. Along the way, she majored briefly in chemistry, served as opinion editor and then editor of her college newspaper, and interned for an international design firm. After graduate school, LeAnn worked first for a small multimedia startup and then a computer science research group. At the startup, she spent her time writing user manuals and scripts for multimedia software used to train railroad engineers.

While writing among geeks, LeAnn became enamored and decided to take one home for herself. After getting married and starting a family, she returned to her adolescent daydreams of writing novels. Writing for many years in an office not much better than an unfinished closet, LeAnn published The Mermaid’s Pendant.

She lives outside Boston with one husband, three children whom she home schools, a dog named Hobbes (after Calvin &), and a cat named Attila. Her biggest fear is public speaking. Her favorite authors are Shakespeare and Jane Austen. If she could only take three books with her to a desert island, she would pack her copy of Shakespeare’s complete works and a collection of Austen’s novels.

Saint Sebastian’s Head is her second novel.

1 Comment

Pingback: Guest Post at Colloquium for Saint Sebastian's Head - Author LeAnn Neal Reilly