Synopsis:

Synopsis:

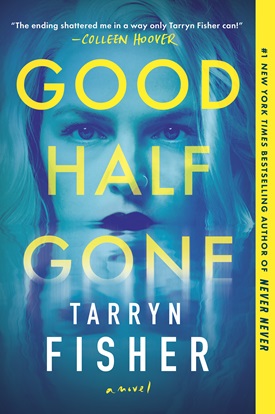

Iris Walsh saw her twin sister Piper get kidnapped. Why does no one believe her?

Iris narrowly escaped her pretty, popular twin sister’s fate as a teenager. She was kidnapped and trafficked, long gone before the police finally agreed to investigate. Months later, Piper’s newborn son, Callum, was dropped on their estranged mother’s doorstep in the dead of night with a note in Piper’s handwriting signed simply, “Twin.”

Now an adult, Iris just wants one thing — proof. Because she knows exactly who took Piper all those years ag, and she has a pretty good idea who Callum’s father is. She just has to get close enough to prove it.

And if the police won’t help, she’ll just have to do it her own way: interning at the isolated Shoal Island Hospital for the criminally insane. Where her target is kept locked away.

But Iris soon realizes that something sinister is bubbling beneath the surface of Shoal Island and the patients aren’t the only ones being observed . . .

Review:

Iris and her twin sister, Piper, were just fifteen years old when Iris witnessed Piper’s kidnapping. Piper was grabbed by three men who also took Iris’s phone, so she ran back into the movie theater where the manager let her use the phone there to summon help and confirmed for police that Iris had indeed arrived with a girl who looked exactly like her. The girls lived with their grandmother, Betty, because their mother, Virginia, was an addict, incapable of caring for them, who lost custody when a teacher requested a wellness check. Every year, on the anniversary of Piper’s abduction, Iris listens to the recording of the 911 call she placed from the lobby of the theater. From her perspective, the police were slow to respond, asking questions that seemed irrelevant. “They were stuck on the phone thing. They wanted to know why the men would take my phone.” The police insinuated that Piper voluntarily left with the three men, abandoning her sister at the theater. Officers patronized and placated Iris, who was “hysterical” and already riddled with shame because “I’d lost my sister. Gran told me to take care of her, and now she was gone,” she recalls. Piper had become “boy crazy” and expelled for engaging in inappropriate behavior with them on campus. Even though Piper claimed to have changed – and become religious — Gran was emphatic: “Don’t let her out of your sight. I mean in. I’m not raising her babies.” Iris learns that Piper’s kidnappers were supposed to grab both of them and is further engulfed in survivor’s guilt.

Three years after Piper’s disappearance, Gran and Iris were able to move into a cozy Seattle home left to Gran by an aunt. It is there they are raising Callum, now nine years old. Thirteen months after Piper vanished, he was left, with the umbilical cord still attached, on Virginia’s doorstep in a box with a blanket and a note: “Iris, daughter of no one, please take care of my son. His name is Callum.” It was signed, “Twin,” and Iris instantly recognized the handwriting as Piper’s. Iris has never understood why, if Piper is still alive, she would leave her child and, more curiously, why she would leave his with their mother, of all people.

Iris and Piper were very different. Piper was popular, while Iris had only a few friends with whom she did not interact outside of school. They fought, deliberately antagonizing each other as only siblings can. But they loved each other and because of their experiences with their mother, who would disappear during drug-induced hazes, leaving the girls on their own for days at a time, “Piper wouldn’t disappear for a night and not tell us. She was a free spirit but a considerate one.”

Iris is now twenty-three years old. Virigina, an unabashed narcissist, is serving a five-year prison sentence for armed robbery and maintains she is “born again.” At sixty-seven, Gran has already survived an ischemic stroke and heart attack, and Iris worries about her health, always careful not to upset her. Iris, who has spent years balancing her studies, caring for Callum, and obsessively searching for Piper, has been accepted into an internship program at Shoal Island Hospital to which she was encouraged to apply by one of her professors. It is a private hospital for the mentally ill, teetering on a cliff and reachable only by ferry. She is convinced that the man responsible for Piper’s abduction resides there. And she is going to at last learn her sister’s fate.

Dr. Leo Grayson is a renowned celebrity psychotherapist who holds two doctorate degrees and has authored several bestselling books. But he has been out of the spotlight for a number of years, and now in his mid-forties, Internet searches only produce the same photos of him taken years ago. He is the only doctor on staff at Shoal Island, which opened in 1944 but has been renovated many times since. Originally an army outpost, it later served as a prison and a home for unwed mothers. Only forty patients are housed there, each one a violent offender who never stood trial because they were ruled incompetent to do so by the courts. Iris will not be dissuaded from breaking any rule necessary in order to access D Hall where five patients are merely housed in solitary confinement, with no effort made to rehabilitate them. She is warned never to venture there unless accompanied by the doctor. But Iris is anxious to do just that, and participate in their therapy sessions, because she has studied all five of them and is certain. “One of them killed my sister.” She does not expect to find herself attracted to the handsome and charming Dr. Grayson . . . and confiding in him. Could that prove to be a fatal mistake?

Through a somewhat unreliable first-person narrative from Iris, which alternates between the past and present, author Tarryn Fisher relates a story that is heartbreaking and full of shocking twists. Iris is a sympathetic character. A steadfast sister who, despite conflicts with her twin, remans devoted to finding out what happened to her and seeking justice not just for Piper, but also for Callum, the innocent little boy who has never known his mother. Iris immediately devoted herself to Callum, enrolling in a home school program so she could serve as his surrogate mother. She adores Gran, a scrappy, streetwise woman who has seen more than her share of disappointment during a life as an exotic dancer, prison guard, and, eventually, librarian. Iris lovingly describes her as “resourceful, tough, smart – and one hundred percent unapologetic. My hero.” She is all too aware of who and what Virginia is, and fiercely protective of her granddaughters and little Callum. The novel succeeds as an examination of the family dynamics, especially the sisters’ relationship. Fisher also credibly depicts the teenage struggles of Iris and Piper, who have vastly different personalities, but are both impacted by childhood traumas. It is also an indictment of police officers who are embroiled in their own scandals and far too quick to write Piper off as just a troubled girl who decided to run away.

Iris is certain that only Gran knows the real reason she applied for the internship, but as Fisher gradually reveals clues to Piper’s fate, it becomes clear that the missing girl naively got involved with people who had nefarious motives. And Iris has brazenly but perhaps foolishly embarked on a mission that has placed her in grave danger.

The mystery surrounding Piper’s kidnapping is an intriguing exploration of contemporary topics including drug abuse and human trafficking, in addition to teenage angst. The gothic atmosphere at Shoal Island effectively heightens the dramatic tension. It is an ominous, oppressive, and frightening setting populated by interesting characters who may or may not compound the dangers Iris faces. The story’s pace accelerates to an action-packed climax, but that aspect of the story is less successful. The ending arrives abruptly and feels rushed, although it is replete with surprises that readers will never quite be able to guess. Fisher provides answers, resolving all aspects of the mindboggling story and bringing it to a satisfying conclusion with a distinctly cinematic quality, albeit through a circuitous route that is ridiculously far-fetched, even for a psychological thriller, a genre which regularly requires readers to suspend their disbelief to varying degrees.

Despite the ending, Good Half Gone is entertaining and absorbing, and readers will find themselves unable to resist cheering for Iris, Gran, and, of course, Callum.

Excerpt from Good Half Gone

“911, what is your emergency?”

“Hello? Help me, please! They took my sister! Please hurry, I don’t know where they are. I can’t find them.” *rustling noise* *yells something* “Oh my god — oh my god. Piper!”

“Ma’am, I need you to calm down so that I can understand you.”

“Okay . . .” *crying*

“Who took your sister?”

“I don’t know! I don’t know them. Two guys. Dupont knows them, I –”

“Miss, what is the address? Where are you?”

“The theater on Pike, . . . the Five Dollar . . .” *crying* “They took my phone, I’m calling from inside the theater.”

“Wait right where you are, someone is going to be there to help shortly. Can you tell me what your name is?”

*crying*

“What is your name? Hello?”

*crying, indecipherable noises*

“Can you tell me your name?”

“Iris . . .”

“What is your sister’s name, Iris? And how old is she?”

“Piper. She’s fifteen.”

“Is she your older sister or younger sister . . . Iris, can you hear me?”

“We’re twins. They just put her in a car and drove away. Please hurry.”

“Can you tell me what kind of vehicle they were driving?”

“I don’t know . . .”

“ — a van, or a sedan — ?”

“It was blue and long. I can’t remember.”

“Did it have four doors or two . . . Iris?”

“Four.”

“And how many men were there?”

“Three.”

“I’m going to stay on the line with you until the officers get there.”

He leans forward, rouses the mouse, and turns off the audio on his computer. Click click clack. I was referred to Dr. Stanford a year ago when my long-term therapist retired. I had the option of finding a new therapist on my own or being assigned someone in the practice. Of course I considered breaking up with therapy all together, but after eight years it felt unnatural not to go. But I was a drinker of therapy sauce: a true believer in the art of feelings. I imagined people felt that way about church. At the end of the day, I told myself that a weird therapist was better than no therapist.

I disliked Allen Stanford on sight. Grubby. He is the grownup version of the kindergarten booger eater. A mouth breather with a slow, stiff smile. I was hoping he’d grow on me.

Dr. Stanford clears his throat.

“That’s hard to listen to for me, so I can only imagine how you must feel.”

Every year, on the anniversary of Piper’s kidnapping, I listen to the recording of the 911 call I made from the lobby of the Five Dollar. When I close my eyes, I can still see the blue diamond carpet and the blinking neon popcorn sign.

“Do you want to take a break?”

“A break from what?”

“It must be hard for you to hear that even now . . . ”

That is true, reliving the worst day of my life never gets easier. The smell of popcorn is attached to the memory, and I feel nauseated. A cold chill sweeps over me. Swallowing the lump in my throat, I nod once.

“What happened after you hung up the phone?”

“I waited…what else could I do? I was afraid they were outside waiting to take me too. My brain hadn’t fully caught up to what was happening. I felt like I was dreaming.”

My voice is weighed down with shame; in the moments after my twin was taken, I was thinking of my own safety, worried that her kidnappers would come back. Why hadn’t I chased the car down the street, or at least paid attention to the license plate so I could give it to the cops? Hindsight was a sore throat.

“I wanted to call Gran.” I shake my head. “I thought I was crazy because I’d dialed her number hundreds of times and I just . . . I forgot. I had to wait for the cops.”

My lungs feel like they’re compressing. I force a deep breath.

“I guess it took five minutes for the cops to get there, but if you asked me that day, I would have said it took an hour.”

When I close my eyes, I can still see the city block in detail— smell the fry oil drifting across the street from the McDonald’s.

“The cops parked their cruiser on the street in front of the theater,” I continue. “I was afraid of them. My mother was an addict — she hated cops. To certain people, cops only show up to take things away, you know?”

He nods like he knows, and maybe he does, maybe he had a mom like mine, but for the last twenty years, he’s been going to Disney World –according to the photos on his desk — and that somehow disqualifies him in my mind as a person who’s had things taken away from him.

I take another sip of water, the memories rushing back. I close my eyes, wanting to remember, but not wanting to feel — a fine line.

I was shaking when I stumbled out of the theater and ran toward the cop car, drunk with shock, the syrupy soda pooling in my belly. My toe hit a crack in the asphalt and I rolled my ankle, scraping it along the side of the curb. I made it to them, staggering and crying, scared out of my mind—and that’s when things had gone from bad to worse.

“Tell me about your exchange with the police,” he prompts. “What, if anything, did they do to help you in that moment?”

The antiquated anger begins festering now, my hands fisting into rocks. “Nothing. They arrived already not believing me. The first thing they asked was if I had taken any drugs. Then they wanted to know if Piper did drugs.”

The one with the watery eyes—I remember him having a lot of hair. It poked out the top of his shirt, tufted out of his ears. The guy whose glasses I could see my face in—he had no hair. But what they had both worn that day was the same bored, cynical expression. I sigh. “To them, teenagers who looked like me did drugs. They saw a tweaker, not a panicked, traumatized, teenage girl.”

“What was your response?”

“I denied it — said no way. For the last six months, my sister had been hanging with a church crowd. She spent weekends going to youth group and Bible study. If anyone was going to do drugs at that point, it would have been me.”

He writes something down on his notepad. Later I’ll try to imagine what it was, but for now I am focused.

“They thought I was lying—I don’t even know about what, just lying. The manager of the theater came outside to see what was going on, and he brought one of his employees out to confirm to the police that I had indeed come in with a girl who looked just like me, and three men. I asked if I could call my gran, who had custody of us.”

“Did they let you?”

“Not at first. They ignored me and just kept asking questions. The bald one asked if I lived with her, but before I could answer his question, the other one was asking me which way the car went. It was like being shot at from two different directions.” I lean forward in my seat to stretch my back. I’m so emotionally spiked, both of my legs are bouncing. I can’t make eye contact with him; I’m trapped in my own story — helpless and fifteen.

“The men who took my sister — they took my phone. The cops wanted to know how I called 911. I told them the manager let me use the phone inside the theater. They were stuck on the phone thing. They wanted to know why the men would take my phone. I screamed, ‘I have no idea. Why would they take my sister?’”

“They weren’t hearing you,” he interjects.

I stare at him. I want to say No shit, Sherlock, but I don’t. Shrinks are here to edit your emotions with adjectives in order to create a TV Guide synopsis of your issues. Today on an episode of Iris in Therapy, we discover she has never felt heard!

“I was hysterical by the time they put me in the cruiser to take me to the station. Being in the back of that car after just seeing Piper get kidnapped — it was like I could feel her panic. Her need to get away. They drove me to the station…” I pause to remember the order of how things happened.

“They let me call my grandmother, and then they put me in a room alone to wait. It was horrible—all the waiting. Every minute of that day felt like ten hours.”

“Trauma often feels that way.”

“It certainly does,” I say. “Have you ever been in a situation that makes you feel that way—like every minute is an hour?” I lean forward, wanting a real answer. Seconds tick by as he considers me from behind his desk. Therapists don’t like to answer questions. I find it hypocritical. I try to ask as many as I can just to make it fair.

Comments are closed.