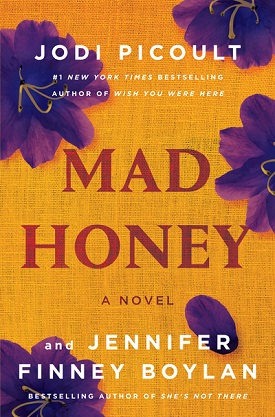

Synopsis:

Synopsis:

Olivia McAfee knows what it’s like to start over. She upended her picture-perfect life — living in Boston, married to a brilliant cardiothoracic surgeon, raising a beautiful son, Asher — when her husband revealed his dark side. She never imagined she would end up back in Adams, her sleepy New Hampshire hometown, living in the house in which she and her brother, Jordan, grew up, and taking over her father’s beekeeping business.

Lily Campanello is familiar with starting over, too. She and her mom have relocated to Adams for her final year of high school, both hoping for a fresh start.

For just a short while, their new beginnings are exactly what Olivia and Lily need.

Their paths cross when Asher, an excellent student and hockey team stand-out, and Lily fall for each other. With Asher, Lily feels truly happy for the first time. Still, she wonders if she can she trust him completely . . .

Then Olivia gets a phone call no parent wants to receive. Lily is dead. Asher is being questioned by the police.

Olivia is adamant that Asher is innocent. But she has seen flashes of his father’s temper in him and, as the case against him unfolds, she realizes he’s hidden more than he’s shared with her.

Mad Honey is a suspensful mystery, as well as an unforgettable love story, and an exploration of what we choose to keep from our past and what we choose to leave behind on our way to becoming ourselves.

Review:

Jodi Picoult is the bestselling author of twenty-nine prior novels, including Wish You Were Here, The Book of Two Ways, A Spark of Light, Change of Heart, Lone Wolf, Keeping Faith, and Nineteen Minutes. She has also penned two young adult novels with her daughter, Samantha Van Leer, which were adapted into a musical entitled Between the Lines. Four of her novels have been adapted into television movies and Her Sister’s Keeper was developed into a film. A graduate of Princeton University, Picoult has won numerous awards.

Jennifer Finney Boylan is a professor, author of novels and short stories, memoirist, and well-known human rights advocate and activitist. advocate for human rights. Her 2003 memoir, She’s Not There: a Life in Two Genders, was the first bestselling book by a transgender American. She has penned seventeen other books, including a subsequent memoir, Good Boy: My Life in 7 Dogs. She served as a Contributing Opinion Writer for the opinion page of the New York Times for fifteen years. She also is a member of the faculty of the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference of Middlebury College, and the Sirenland Writers’ Conference in Positano, Italy. She is the inaugural Anna Quindlen Writer in Residence at Barnard College of Columbia University. She was the subject of documentaries on CBS News’ 48 Hours and The History Channel. She serves on the Board of Trustees of PEN America, a nonprofit organization that advocates for authors, readers, and freedom of expression, and is a past member of the Board of Directors of GLAAD and Board of Trustees of the Kinsey Institute for Research on Sex, Gender, and Reproduction.

The genesis of Picoult and Boylan’s collaboration on Mad Honey is literally something out of a dream . . . In May 2017, Boylan awoke to the realization that she had dreamed she was writing a novel with Picoult about a “girl who died; her boyfriend, who had been accused of her murder; and the boy’s mother, who was torn between the compelling evidence of her son’s guilt and the love she bore for him in her heart.” Boylan had been a fan since reading Picoult’s 2003 novel, The Pact. Picoult enjoyed Boylan’s memoir, She’s Not There, and supplied a complimentary blurb for Long Black Veil, her 2016 novel. When Boylan Tweeted, “I dreamed I was co-authoring a book with Jodi Picoult,” she soon received a private message from Picoult asking what the book was about. Picoult, who is known for examining thorny social issues through her fiction and had been contemplating a book focused on transgender rights, was intrigued. Picoult imagined “creating a trans character who was so real and compelling that . . . [readers would] love her for who she was, not what she was.” They began crafting the book in early 2020, just as the world shut down because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The book opens on December 7, 2018, the day on which Olivia receives the kind of phone call every parent dreads. She is a beekeeper who returned to her home town of Adams, New Hampshire, twelve years ago with her son, Asher, now a high school senior. The story is related through two first-person narratives. From Picoult’s perspective, the division of labor was mandated by the subject matter. Thus, it was agreed that Picoult would draft Olivia’s account. Asher has been dating Lily since September. She is a new student who relocated from Point Reyes, California, with her mother, Ava, a U.S. Forest Ranger who accepted a desk job in order to facilitate her transfer to New Hampshire. Lily’s narrative, drafted by Boylan, begins on the same day as Olivia’s and is presented on alternating chapters. However, as Olivia’s account moves forward in time, Lily’s moves incrementally in reverse chronological order. The co-authors agreed, however, that they would each write at least one chapter in the other character’s voice, and re-edit each other’s work in order to ensure continuity and consistency. The technique worked, leaving even the authors unable, after revisions, to recall which portions they penned.

Olivia is a strong, protective mother who has already taken bold steps to protect her only child. As the story progresses, she tells the story of how she met and fell in love with Asher’s father, as well as why their marriage ended in divorce. Revealing those details gradually, as Olivia’s strength, resolve, and faith in her son is tested, proves highly effective. Specific junctures in the investigation into Lily’s death — Asher’s interrogation, arrest, and the ensuing trial — dovetail with past events to provide insight into Olivia’s psyche. She loves Asher unconditionally, but there is strong circumstantial evidence linking him to Lily’s death, which is ruled a homicide. Current events trigger Olivia’s memories of incidents that occurred during her marriage, culminating in the moment when she knew it had reached the proverbial point of no return. Olivia took steps to ensure that Asher would be protected from his father’s influence, so Asher has not had a relationship with him since he was six years old. Still, Olivia is unsure about how much Asher remembers of their life with his father and worries that Asher could have inherited undesirable traits from him. Her brother, Jordan, one of New Hampshire’s most famous defense attorneys (who has appeared in prior Picoult novels), agrees to defend Asher and has he explains the legal significance of the evidence against him, Olivia’s belief in Asher’s innocence wavers. She understandably questions whether her child has a capacity for violence that resulted in the death of the girl he loved. And that is one thing she is sure about: Asher loved Lily. But Olivia also learns that Asher has kept secrets from her, invalidating some of her assumptions about her son’s character and further challenging her belief in his innocence.

Olivia is a highly sympathetic character with whom readers, especially parents, will readily empathize. Moving to Adams in order to keep Asher safe and shielded from his father’s example was a sacrifice, but she does not regret having returned to her hometown for the sake of her son. Asher is poised to graduate from high school and begin college, leaving Olivia to think about her own needs and desires for the first time in years. She liked Lily from the moment she met her, and was thrilled to see Asher happy. Picoult (and Boylan) compassionately and believably portray Olivia’s internal emotional struggle as she desperately wants to believe that her child is not a killer, and questions her parenting and whether she did enough to prevent him from becoming like his father. Like Lily, Olivia knows Asher to be a “gentle, gentle spirit” but, also like Lily, she has seen his temper flare and it frightened her. Her anguish, as Asher’s bright future teeters, is palpable and credible, especially when Jordan competently and frankly explains the legal peril in which Asher finds himself.

Lily’s story also begins on “the day of” her death. Five days earlier, Asher picked her up at her house, promising a wonderful surprise. But things did not go as Asher hoped and Lily has missed the past three days of school because she hasn’t felt well, but she is also avoiding Asher and her classmates. Lily is a talented cellist who, like Asher, is excited about graduation and college. She considers her mother, “Ranger Mom,” not just a “badass,” but also her staunchest protector, defender, and friend. Indeed, Lily reveals how Ava, like Olivia, has proven that she will do whatever is necessary to take care of her daughter, shield her from harm, and help her lead a happy life, authentically. Because readers are informed immediately that Lily has died, getting to know her and understand her emotional journey is bittersweet, but exponentially more poignant and impactful. While Asher’s future hangs in the balance, Lily’s has been obliterated, leaving her mother grieving and, like Olivia, wondering if Asher could be capable of taking her only child’s life, just as she was on the brink of attaining so many of her goals. Like Asher, Lily’s relationship with her father has been troubled and she is estranged from him. She has even lied to Asher, telling him her father is dead in order to avoid explaining the reasons why he is no longer part of her life. She says, “People always talk about how their love for you is unconditional. Then you reveal your most private self to them, and you find out how many conditions there are in unconditional love.” At the beginning of their romance, there is more about Lily that Asher does not know, and Lily fears that if Asher learns the real reasons why she and her mother moved to Adams, their relationship will end.

Picoult is known for her skillful misdirection and shocking revelations, and Mad Honey is no exception. Readers are expertly drawn into Lily’s compelling story, a big portion of which is, of course, focused on her relationship with Asher and its evolution. It is deeply moving, in no small part because Boylan flawlessly captures Lily’s teen tone, style, and angst. Boylan deftly conveys Lily’s emotional struggles, joys, and determination to navigate the world as her true self, buoyed by her mother’s tireless and unconditional support. She also educates readers by setting forth information in a straight-forward manner that enhances readers’ understandings of various issues and the practical ways in which they can be addressed. She and Picoult thoroughly enmesh readers in Lily’s challenges before abruptly revealing, in dramatic fashion, one salient fact that decimates assumptions held up to that point and forces readers to view Lily’s journey through a completely different lens. Which is, of course, the point. With knowledge of what Lily went through and who she was, Picoult and Boylan ask readers to see her in exactly the same way they did before they were made privy to private details about her.

In true Picoult fashion, Mad Honey is a clever and absorbing murder mystery featuring riveting courtroom scenes that is marred only by its predictable and, frankly, overused resolution. The story is punctuated with details about bees and beekeeping that parallel the action in the characters’ lives, as well as a deeply touching and thought-provoking meditation on social issues. It is an examination of motherhood, depicted through the characters of Olivia and Ava, both of whom are called upon to stand firm in their convictions about and defense of their child. They have both “protected them from their fathers, giving enough love to spackle over the hate.” They have sacrificed their own dreams in order to shield their children from physical and emotional abuse, as well as the aftermath thereof. Olivia is undergoing the unbelievably stressful experience of seeing a child accused of a heinous crime, facing possible imprisonment for life, and digging deep within her emotional resources to be balance the need to pragmatically evaluate the evidence and its implications against what she knows about the child raised. In contrast, there is nothing more Ava can do for her child except mourn and remember her, and hope that justice is served.

Mad Honey is also a thoughtful exploration of what it means to be one’s true self and how hard that can be when others — sometimes even those who should steadfastly accept and love us unconditionally — refuse to accept us as we are. It’s the candid and excruciatingly heartbreaking story of a girl who wanted most to be, and be seen and acknowledged as just that: a girl whose internal self-concept matched what she presented to the world. Through their characters, they ponder the concept of privacy vs. secrecy. “There is no set of rules that dictates what you owe someone you love. What parts of your past should be disclosed? . . . Where is the line between keeping something private, and being dishonest? What if the worst happens? What if honesty is the thing that breaks you apart?”

Boylan says that as the manuscript was nearly finalized, she was “dogged by two melancholy thoughts” that readers will undoubtedly share. First, for Ava who lost and will always miss her only child. But also for Lily, who will not go on to college or have all of the other wonderful life experiences to which young people look forward, in no small measure because far too many real girls like her are killed every year. But Boylan hopes that by telling Lily’s story, she will “open hearts” and “shine a light on issues that you may have never thought about in this way before.” As Lily explains, “People want the world to be simple. But gender isn’t simple, much as some might want it to be. The fact that it’s complicated — that there’s a whole spectrum of ways of being in the world — is what makes it a blessing. Surely nature — or god, or the universe — is full of miracles and wild invention and things way beyond our understanding, no matter how hard we try. We aren’t here on earth in order to bend over backwards to resemble everybody else. We’re here to be ourselves, in all our gnarly brilliance.”

For Picoult’s part, she doesn’t want readers to take anything away from reading Mad Honey. Rather, she wants readers “to give — a chance, a thought, a damn. . . . [D]ifference is a construct. We are all flawed, complicated, scarred dreamers; we have more in common with each other than we don’t. Sometimes making the world a better place just involves creating space for the people who are already in it.” And that’s the clear message imbued in Mad Honey, a book that should be required reading in every high school and college in America because that’s the deceptively simple and quite timely point that Picoult and Boylan make through its characters.

Excerpt from Mad Honey

OLIVIA ~ 1

DECEMBER 7, 2018

The day of

From the moment I knew I was having a baby, I wanted it to be a girl. I wandered the aisles of department stores, touching doll-size dresses and tiny sequined shoes. I pictured us with matching nail polish—me, who’d never had a manicure in my life. I imagined the day her fairy hair was long enough to capture in pigtails, her nose pressed to the glass of a school bus window; I saw her first crush, prom dress, heartbreak. Each vision was a bead on a rosary of future memories; I prayed daily.

As it turned out, I was not a zealot . . . only a martyr.

When I gave birth, and the doctor announced the baby’s sex, I did not believe it at first. I had done such a stellar job of convincing myself of what I wanted that I completely forgot what I needed. But when I held Asher, slippery as a minnow, I was relieved.

Better to have a boy, who would never be someone’s victim.

MOST PEOPLE IN Adams, New Hampshire, know me by name, and those who don’t, know to steer clear of my home. It’s often that way for beekeepers—like firefighters, we willingly put ourselves into situations that are the stuff of others’ nightmares. Honeybees are far less vindictive than their yellow jacket cousins, but people can’t often tell the difference, so anything that stings and buzzes comes to be seen as a potential hazard. A few hundred yards past the antique Cape, my colonies form a semicircular rainbow of hives, and most of the spring and summer the bees zip between them and the acres of blossoms they pollinate, humming a warning.

I grew up on a small farm that had been in my father’s family for generations: an apple orchard that, in the fall, sold cider and donuts made by my mother and, in the summer, had pick-your-own strawberry fields. We were land-rich and cash-poor. My father was an apiarist by hobby, as was his father before him, and so on, all the way back to the first McAfee who was an original settler of Adams. It is just far enough away from the White Mountain National Forest to have affordable real estate. The town has one traffic light, one bar, one diner, a post office, a town green that used to be a communal sheep grazing area, and Slade Brook—a creek whose name was misprinted in a 1789 geological survey map, but which stuck. Slate Brook, as it should have been written, was named for the eponymous rock mined from its banks, which was shipped far and wide to become tombstones. Slade was the surname of the local undertaker and village drunk, who had a tendency to wander off when he was on a bender, and who ironically killed by drowning in six inches of water in the creek.

When I first brought Braden to meet my parents, I told him that story. He had been driving at the time; his grin flashed like lightning. But who, he’d asked, buried the undertaker?

Back then, we had been living outside of DC, where Braden was a resident in cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins and I worked at the National Zoo, trying to cobble together enough money for a graduate program in zoology. We’d only been together three months, but I had already moved in with him. We were visiting my parents that weekend because I knew, viscerally, that Braden Fields was the one.

On that first trip back home, I had been so sure of what my future would hold. I was wrong on all counts. I never expected to be an apiarist like my father; I never thought I’d wind up sleeping in my childhood bedroom once again as an adult; I never imagined I’d settle down on a farm my older brother, Jordan, and I once could not wait to leave. I married Braden; he got a fellowship at Mass General;we moved to Boston; I was a doctor’s wife. Then, almost a year to the day of my wedding anniversary, my father didn’t come home one evening after checking his hives. My mother found him, dead of a heart attack in the tall grass, bees haloing his head.

My mother sold the piece of land that held our apple orchard to a couple from Brooklyn. She kept the strawberry fields but was thoroughly at a loss when it came to my father’s hives. Since my brother was busy with a high-powered legal career and my mother was allergic to bees, the apiary fell to me. For five years, I drove from Boston to Adams every week to take care of the colonies. After Asher was born, I’d bring him with me, leaving him in the company of my mother while I checked the hives. I fell in love with beekeeping, the slow-motion flow of pulling a frame out of a hive, the Where’s Waldo? search for the queen. I expanded from five colonies to fifteen. I experimented with bee genetics with colonies from Russia, from Slovenia, from Italy. I signed pollination contracts with the Brooklynites and three other local fruit orchards, setting up new hives on their premises. I harvested, processed, and sold honey and beeswax products at farmers’ markets from the Canadian border to the suburbs of Massachusetts. I became, almost by accident, the first commercially successful beekeeper in the history of apiarist McAfees. By the time Asher and I moved permanently to Adams, I knew I might never get rich doing this, but I could make a living.

My father taught me that beekeeping is both a burden and a privilege. You don’t bother the bees unless they need your help, and you help them when they need it. It’s a feudal relationship: protection in return for a percentage of the fruits of their labors.

He taught me that if a body is easily crushed, it develops a weapon to prevent that from happening.

He taught me that sudden movements get you stung.

I took these lessons a bit too much to heart.

On the day of my father’s funeral, and years later, on the day of my mother’s, I told the bees. It’s an old tradition to inform them of a death in the family; if a beekeeper dies, and the bees aren’t asked to stay on with their new master, they’ll leave. In New Hampshire, the custom is to sing, and the news has to rhyme. So I draped each colony with black crepe, knocked softly, crooned the truth. My beekeeping net became a funeral veil. The hive might well have been a coffin.

BY THE TIME I come downstairs that morning, Asher is in the kitchen. We have a deal, whoever gets up first makes the coffee. My mug still has a wisp of steam rising. He is shoveling cereal into his mouth, absorbed in his phone.

“Morning,” I say, and he grunts in response.

For a moment, I let myself stare at him. It’s hard to believe that the soft-centered little boy who would cry when his hands got sticky with propolis from the hives can now lift a super full of forty pounds of honey as if it weighs no more than his hockey stick. Asher is over six feet tall, but even as he was growing, he was never ungainly. He moves with the kind of grace you find in wildcats, the ones that can steal away a kitten or a chick before you even realize they’ve gone. Asher has my blond hair and the same ghost-green eyes, for which I have always been grateful. He carries his father’s last name, but if I also had to see Braden every time I looked at my son, it would be that much harder.

I catalog the breadth of his shoulders, the damp curls at the nape of his neck; the way the tendons in his forearms shift and play as he scrolls through his texts. It’s shocking, sometimes, to be confronted with this when a second ago he sat on my shoulders, trying to pull down a star and unravel a thread of the night.

“No practice this morning?” I ask, taking a sip of my coffee. Asher has been playing hockey as long as we’ve lived here; he skates as effortlessly as he walks. He was made captain as a junior and reelected this year, as a senior. I never can remember whether they have rink time before school or after, as it changes daily.

His lips tug with a slight smile, and he types a response into his phone, but doesn’t answer.

“Hello?” I say. I slip a piece of bread into the ancient toaster, which is jerry-rigged with duct tape that occasionally catches on fire. Breakfast for me is always toast and honey, never in short supply.

“I guess you have practice later,” I try, and then provide the answer that Asher doesn’t. “Why yes, Mom, thanks for taking such an active interest in my life.”

I fold my arms across my boxy cable-knit sweater. “Am I too old to wear this tube top?” I ask lightly.

Silence.

“I’m sorry I won’t be here for dinner, but I’m running away with a cult.”

I narrow my eyes. “I posted that naked photo of you as a toddler on Instagram for Throwback Thursday.”

Asher grunts noncommittally. My toast pops up; I spread it with honey and slide into the chair directly across from Asher. “I’d really prefer that you not use my Mastercard to pay for your Pornhub subscription.”

His eyes snap to mine so fast I think I can hear his neck crack. “What? ”

“Oh, hey,” I say smoothly. “Nice to have your attention.”

Asher shakes his head, but he puts down his phone. “I didn’t use your Mastercard,” he says.

“I know.”

“I used your Amex.”

I burst out laughing.

“Also: never ever wear a tube top,” he says. “Jesus.”

“So you were listening.”

“How could I not?” Asher winces. “Just for the record, nobody

else’s mother talks about porn over breakfast.”

“Aren’t you the lucky one, then.”

“Well,” he says, shrugging. “Yeah.” He lifts his coffee mug, clinks

it to mine, and sips.

I don’t know what other parents’ relationships are like with their

children, but the one between me and Asher was forged in fire and, maybe for that reason, is invincible. Even though he’d rather be caught dead than have me throw my arms around him after a winning game, when it’s just the two of us, we are our own universe, a moon and a planet tied together in orbit. Asher may not have grown up in a household with two parents, but the one he has would fight to the death for him.

“Speaking of porn,” I reply, “how’s Lily?”

He chokes on his coffee. “If you love me, you will never say that sentence again.”

Asher’s girlfriend is tiny, dark, with a smile so wide it completely changes the landscape of her face. If Asher is strength, then she is whimsy—a sprite who keeps him from taking himself too seriously; a question mark at the end of his predictable, popular life. Asher’s had no shortage of romantic entanglements with girls he’s known since kindergarten. Lily is a newcomer to town.

This fall, they have been inseparable. Usually, at dinner, it’s Lily did this or Lily said that.

“I haven’t seen her around this week,” I say.

Asher’s phone buzzes. His thumbs fly, responding.

“Oh, to be young and in love,” I muse. “And unable to go thirty seconds without communicating.”

“I’m texting Dirk. He broke a lace and wants to know if I have extra.”

One of the guys on his hockey team. I have no actual proof, but I’ve always felt like Dirk is the kid who oozes charm whenever he’s in front of me and then, when I’m gone, says something vile, like Your mom is hot, bro.

“Will Lily be at your game on Saturday?” I ask. “She should come over afterward for dinner.”

Asher nods and jams his phone in his pocket. “I have to go.” “You haven’t even finished your cereal—”

“I’m going to be late.”

He takes a long last swallow of coffee, slides his backpack over his

shoulder, and grabs his car keys from the bowl on the kitchen counter. He drives a 1988 Jeep he bought with the salary he made as a counselor at hockey camp.

“Take a coat!” I call, as he is walking out the door. “It’s—”

His breath fogs in the air; he slides behind the steering wheel and turns the ignition.

“Snowing,” I finish.

DECEMBER IS WHEN beekeepers catch their breath. The fall is a flurry of activity, starting with the honey harvest, then managing mite loads, and getting the bees ready to survive a New Hampshire winter. This involves mixing up a heavy sugar syrup that gets poured into a hive top feeder, then wrapping the entire hive for insulation before the first cold snap. The bees conserve their energy in the winter, and so should the apiarist.

I’ve never been very good with downtime.

There’s snow on the ground, and that’s enough to send me up to the attic to find the box of Christmas decorations. They’re the same ones my mother used when I was little—ceramic snowmen for the kitchen table; electric candles to set in each window at night, a string of lights for the mantel. There’s a second box, too, with our stockings and the ornaments for the tree, but it’s tradition that Asher and I hang those together. Maybe this weekend we will cut down our tree. We could do it after his game on Saturday, with Lily.

I’m not ready to lose him.

The thought stops me in my tracks. Even if we do not invite Lily to come choose a tree with us—to decorate it as he tells her the story behind the stick reindeer ornament he made in preschool or the impossibly tiny baby shoes, both his and mine, that we always hang on the uppermost branches—soon another will join our party of two. It is what I want most for Asher—the relationship I don’t have. I know that love isn’t a zero-sum game, but I’m selfish enough to hope he’s all mine for a little while longer.

I lug the first box down the attic stairs, hearing Asher’s voice in my head: Why didn’t you wait? I could have carried it down for you. Glancing through the open door of his bedroom, I roll my eyes at his unmade bed. It drives me crazy that he does not tuck in his sheets; it drives him just as crazy to do it, when he knows he’s just going to crawl back in in a few hours. With a sigh, I put the box down and walk into Asher’s room. I yank the sheets up, straightening his covers. As I do, a book falls to the floor.

It’s a blank journal, in which Asher has sketched in colored pencil. There’s a bee, hovering above an apple blossom, so close that you can see the working mandible and the pollen caught on her legs. There’s my old truck, a 1960 powder-blue Ford that belonged to my father.

Asher has always had this softer side, I love him all the more for it. It was clear when he was little that he had artistic talent, and once I even enrolled him in a painting class, but his hockey friends found out. When he messed up doing a passing drill, one of them said he should maybe stop holding his stick like Bob Ross held a brush, and he dropped art. Now, when he draws, it’s in private. He never shows me his work. But we’ve also gotten college brochures in the mail from RISD and SCAD, and I wasn’t the one to request them.

I flip the next few pages. There is one drawing that is clearly me, although he’s captured me from behind, as I stand at the sink. I look tired, worn. Is that what he thinks of me? I wonder.

A chipmunk, eyes bright with challenge. A stone wall. A girl— Lily?—with her arm thrown over her eyes, lying on a bed of leaves, naked from the waist up.

Immediately, I drop the book like it’s burning. I press my palms against my cheeks.

It’s not like I didn’t think he was intimate with his girlfriend; but then again, it’s not like we talked about it, either. At one point, when he started high school, I proactively started buying condoms and leaving them very matter-of-factly with the usual pharmacy haul of deodorant and razor blades and shampoo. Asher loves Lily—even if he hasn’t told me this directly, I see it in the way he lights up when she sits down beside him, how he checks her seatbelt when she gets into his car.

After a minute, I mess up Asher’s sheets and comforter again. I tuck the journal under a fold of the linens, pick up the pair of socks, and close the door of the bedroom behind me

I hoist the Christmas box into my arms again, thinking two things: that memories are so heavy; and that my son is entitled to his secrets.

BEEKEEPING IS THE world’s second-oldest profession. The first apiarists were the ancient Egyptians. Bees were royal symbols, the tears of Re, the sun god.

In Greek mythology, Aristaeus, the god of beekeeping, was taught by nymphs to tend bees. He fell in love with Orpheus’s wife, Eurydice. When she was dodging his advances, she stepped on a snake and died. Orpheus went to hell itself to bring her back, and Eurydice’s nymph sisters punished Aristaeus by killing all his bees.

The Bible promises a land of milk and honey. The Koran says paradise has rivers of honey for those who guard against evil. Krishna, the Hindu deity, is often shown with a blue bee on his forehead. The bee itself is considered a symbol of Christ: the sting of justice and the mercy of honey, side by side.

The first voodoo dolls were molded from beeswax; an oungan might tell you to smear honey on a person to keep ghosts at bay; a manbo would make little cakes of honey, amaranth, and whiskey, which, eaten before the new moon, could show you your future.

I sometimes wonder which of my prehistoric ancestors first stuck his arm into a hole in a tree. Did he come out with a handful of honey, or a fistful of stings? Is the promise of one worth the risk of the other?

WHEN THE INSIDE of the house is draped with its holiday jewelry, I pull on my winter boots and a parka and hike through the acreage of the property to gather evergreen boughs. This requires me to skate the edges of the fields with the few apple trees that still belong to my family. Against the frosty ground, they look insidious and witchy, their gnarled arms reaching, the wind whispering in the voice of dead leaves, Closer, closer. Asher used to climb them; once, he got so high that I had to call the fire department to pull him down, as if he were a cat. I swing my handsaw as I slip into the woods behind the orchard, twigs crunching underneath my footsteps. There are only so many trees whose feathered limbs I can reach; most are higher than I can reach on my tiptoes, but there’s satisfaction in gathering what I can. The pile of pine and spruce and fir grows, and it takes me three trips to bring it all back across the orchard fields to the porch of the farmhouse.

By the time I’ve got my raw materials—the branches and a spool of florist wire—my cheeks are flushed and bright and the tips of my ears are numb. I lay out the evergreens on the porch floor, trimming them with clippers, doubling and tripling the boughs so that they are thick. In the Christmas box I carried down earlier is a long rope of lights that I’ll weave through my garland when this step is finished; then I can affix the greenery around the frame of the front door.

I am not sure what it is that makes me think something is watching me.

All the hair stands up on the back of my neck, and I turn slowly toward the barren strawberry fields.

In the snow, they look like a swath of white cotton. This late in the year, the back of the field is wreathed in shadow. In the summertime, we get raccoons and deer going after the strawberries; from time to time there’s a coyote. When it’s nearly winter, though, the predators have mostly squirreled themselves away in their dens—

I take off at a dead run for my beehives.

Before I even reach the electric fence that surrounds them, the smell of bananas is pungent—the surest sign of bees that are pissed off. Four hives are sturdy and quiet, hunkered tight within their insulation. But the box all the way to the right has been ripped to splinters. I name all my queen bees after female divas: Adele, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Whitney, and Mariah. Taylor, Britney, Miley, Aretha, and Ariana are in the apple orchard; on other contracts I have Sia, Dionne, Cher, and Katy. The hive that has been attacked is Celine’s.

One side of the electric fence has been barreled through, trampled. Struts of wood from the hive are scattered all over the snowy ground; hunks of Styrofoam have been clawed to shreds. I stumble over a piece of broken honeycomb with a bear print in it.

I narrow my eyes at the dark line where the field turns into forest, but the bear is already gone. The bees would have killed themselves, literally, to get rid of their attacker—stinging until it lumbered away.

It’s not the first time I have had a bear attack a hive, but it’s the latest it has ever happened in the beekeeping season.

I walk toward the brush near the edge of the field, trying to find any remaining bees that might not have frozen. A small knot seethes and drips, dark as molasses, on the bare crotch of a sugar maple. I cannot see Celine, but if the bees have absconded there is a chance she is with them.

Sometimes, in the spring, bees swarm. You might find them like this, in the bivouac stage—the temporary site before they fly off to whatever they’ve decided should be their new home.

When bees swarm in the spring, it’s because they’ve run out of space in the hive.

When bees swarm in the spring, they’re full of honey and happy and calm.

When bees swarm in the spring, you can often recapture them, and set them up in a new box, where they have enough room for their brood cells and pollen and honey.

This is not a swarm. These bees are angry and these bees are desperate.

“Stay,” I beg, and then I run back to the farmhouse as fast as I can.

It takes me three trips, each a half mile across the fields, skidding on the dusting of snow. I have to haul out a new wooden base and an empty hive from a colony that failed last year, into which I will try to divert the bees; I have to grab my bee kit from the basement, where I’ve stored it for the winter—my smoker and hive tool, some wire and a bee brush, my hat and veil and gloves. I am sweating by the time I am finished, my hands shaking and sausage-fingered from the cold. Clumsily, I grab the few frames that can be salvaged from the bear’s attack and set them into the brood box. I sew some of the newly broken comb onto the frames with wire, hoping that the bees will be attracted back to the familiar. When the new box is set up, I walk toward the sugar maple.

The light is so low now, because dusk comes early. I see the motion of the bees more than their actual writhing outline. If Asher were here, I could have him hold the brood box directly below the branch while I scoop the bees into it, but I’m alone.

It takes several tries for me to light a curl of birch bark to ignite my smoker; there’s just enough wind to make it difficult. Finally, a red ember sparks, and I drop it into the little metal pot, onto a handful of wood shavings. Smoke pipes out of the narrow neck as I pump the bellows a few times. I give a few puffs near the bees; it dulls their senses and takes the aggressive edge off.

I pull on my hat and veil and lift the same handsaw I used on the evergreen boughs. The branch is about six inches too high for me to reach. Cursing, I lug the broken wooden base of the old frame underneath the tree and try to gingerly balance on what’s left of it. The odds are about equal that I will either manage to saw down the branch or break my ankle. I nearly sob with relief when the branch is free, and carry it slowly and gently to the new hive. I give it a sharp jerk, watching the bees rain down into the box. I do this again, praying that the queen is one of them.

If it were warmer, I’d know for sure. A few bees would gather on the landing board with their butts facing out, fanning their wings and nasonoving—spreading pheromones for strays to find their way home. That’s a sign that the hive is queenright. But it’s too cold, and so I pull out each frame, scanning the frenzy of bees. Celine, thank God, is a marked queen—I spy the green painted dot on her long narrow back and pluck her by the wings into a queen catcher, a little plastic contraption that looks like those butterfly clips for hair. The queen catcher will keep her safe for a couple of days while they all get used to the new home. But it also guarantees that the colony won’t abscond. Sometimes, bees just up and leave with their queen if they don’t like their circumstances. If the queen is locked up, they will not leave without her.

I let a puff of smoke roll over the top of the box, again hoping to calm the bees. I try to set the queen catcher between frames of comb, but my fingers are stiff with the cold and keep slipping. When my hand strikes the edge of the wooden box, one of the worker bees sinks her stinger into me.

“Motherfucker.” I gasp, dancing backward from the hive. A cluster of bees follow me, attracted by the scent of the attack. I cradle my palm, tears springing to my eyes.

I tear off my hat and veil, bury my face in my hands. I can take all the best precautions for this queen; I can feed the bees sugar syrup and insulate their new brood box; I can pray as hard as I want—but this colony does not have a chance of surviving the winter.They simply will not have enough time to build up the stores of honey that the bear has robbed.

And yet. I cannot just give up on them.

So I gently set the telescoping cover on the box and lift my bee kit with my good hand. In the other, I hold a snowball against the sting as a remedy. I trudge back to the farmhouse. Tomorrow, I’ll give them the kindness of extra food in a hive-top feeder and I’ll wrap the new box, but it’s hospice care. There are some trajectories you cannot change, no matter what you do.

Back home, I am so absorbed in icing my throbbing palm that I don’t notice it’s long past dinnertime, and Asher isn’t home.

THE FIRST TIME it happened, it was over a password.

I had only just signed up for Facebook, mostly so that I could see pictures of my brother, Jordan, and his wife, Selena. Braden and I were living in a brownstone on Mass Ave while he did his Mass General fellowship in cardiac surgery. Most of our furniture had come from yard sales in the suburbs that we would drive to on weekends. One of our best finds came from an old lady who was moving to an assisted living community. She was selling an antique rolltop desk with claw-feet (I said it was a gryphon; Braden said eagle). It was clearly an antique, but someone had stripped it of its original finish, so it wasn’t worth much, and more to the point, we could afford it. It wasn’t until we got it home that we realized it had a secret compartment—a narrow little sliver between the wooden drawers that was intended to look decorative, but pulled loose to reveal a spot where documents and papers could be hidden. I was delighted, naturally, hoping for the combination to an old safe full of gold bullion or a torrid love letter, but the only thing we found inside was a paper clip. I had pretty much forgotten about its existence when I had to choose a password for Facebook, and find a place to store it for when I inevitably forgot what I’d picked. What better place than in the secret compartment?

We had initially bought the antique desk so that Braden could study at it, but when we realized that his laptop was too deep for the space, it became decorative, tucked in an empty space at the bottom of the stairs. We kept our car keys there, and my purse, and an occasional plant I hadn’t yet murdered. Which is why I was so surprised to find Braden sitting in front of it one evening, fiddling with the hidden compartment.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

He reached inside and triumphantly pulled out the piece of paper. “Seeing what secrets you keep from me,” he said.

It was so ridiculous I laughed. “I’m an open book,” I told him, but I took the paper out of his hand.

His eyebrows raised. “What’s on there?” “My Facebook password.”

“So what?”

“So,” I said, “it’s mine.”

Braden frowned. “If you had nothing to hide, you’d show it to me.”

“What do you think I’m doing on Facebook?” I said, incredulous. “You tell me,” Braden replied.

I rolled my eyes. But before I could say anything, his hand shot

out for the paper.

PEPPER70. That’s what it said. The name of my first dog and my birth year. Blatantly uninspired; something he could have figured out on his own. But the principle of the whole stupid argument kicked in, and I yanked the page away before he could snatch it.

That’s when it changed—the tone, the atmosphere. The air went still between us, and his pupils dilated. He reached out, striking like a snake, and grabbed my wrist.

On instinct, I pulled back and darted up the stairs. Thunder, him running behind me. My name twisted on his lips. It was silly; it was stupid; it was a game. But it didn’t feel like one, not the way my heart was hammering.

As soon as I made it to our bedroom I slammed the door shut. Leaning my forehead against it, I tried to catch my breath.

Braden shouldered it open so hard that the frame splintered.

I didn’t realize what had happened until my vision went white and I felt a hammer between my eyes. I touched my nose and my fingers came away red with blood.

“Oh my God,” Braden murmured. “Oh my God, Liv. Jesus.” He disappeared for a moment and then he was holding a hand towel to my face, guiding me to sit on the bed, stroking my hair.

“I think it’s broken,” I choked out.

“Let me look,” he demanded. He gently peeled away the bloody cloth and with a surgeon’s tender hands touched the ridge of my brow, the bone beneath my eyes. “I don’t think so,” he said, his voice frayed.

Braden cleaned me up as if I were made of glass and then he brought me an ice pack. By then, the stabbing pain was gone. I ached, and my nose was stuffy. “My fingers are too cold,” I said, dropping the ice, and he picked it up and gently held it against me. I realized his hands were trembling and that he couldn’t look me in the eye.

Seeing him so shaken hurt even more than my injury.

So I covered his hand with mine, trying to comfort. “I shouldn’t have been standing so close to the door,” I murmured.

Finally, Braden looked at me, and nodded slowly. “No. You shouldn’t have.”

…

I HAVE SENT a half dozen texts to Asher, who hasn’t written back. Each one is a little angrier. For someone who seemingly has no trouble interrupting his life to text his girlfriend and Dirk, he has selective communication skills when he wants to. Most likely he was invited to eat dinner somewhere and didn’t bother to tell me.

I decide that as punishment, I will make him clean up the evergreens still strewn across the porch, since my bee-stung hand hurts too much for me to finish stringing the garland.

On the kitchen table is a small bundle of newspaper, which I carefully unwrap. It was placed in the decoration box by mistake, but it belongs in the one with our Christmas ornaments. It’s my favorite—a hand-blown glass bulb in swirls of blue and white, with a drippy curl of frozen glass at the top through which a wire has been threaded for hanging. Asher made it for me when he was six, after we left Braden behind in Boston, and I got a divorce. I had a booth at a county fair that fall, selling honey and beeswax products, and an artisanal glassblower befriended Asher and invited him to watch her in her workshop. Unbeknownst to me, she helped him make an ornament for me as a gift. I loved it, but what made it truly magical was that it was a time capsule. Frozen in that delicate globe was Asher’s childhood breath. No matter how old he was or how big he grew, I would always have that.

Just then my cellphone rings.

Asher. If he’s not texting, he knows he’s in trouble.

“You better have a good excuse,” I begin, but he cuts me off. “Mom, I need you,” Asher says. “I’m at the police station.” Words scramble up the ladder of my throat. “What? Are you all right?”

“I …I’m …no.”

I look down at the ornament in my hand, this piece of the past. “Mom,” Asher says, his voice breaking. “I think Lily’s dead.”

Comments are closed.