Synopsis:

Synopsis:

1863: In a small Creole cottage in New Orleans, Stella, an ingenious young Black woman, embroiders intricate maps on repurposed cloth to aid enslaved men as they flee to join the Union Army. Bound to a man who would kill her if he knew of her clandestine activities, Stella has to hide not only her efforts but her love for William, a Black soldier and gifted flutist.

In New York City, a Jewish woman stitches a quilt for her husband, Jacob Kling, a musician who is stationed in Louisiana with the Union Army. Between abolitionist meetings, Lily rolls bandages and crafts quilts with her sewing circle for other soldiers, hoping for their safe return home.

When months go by without word from Jacob, Lily resolves to make the perilous journey South to search for him and will not be dissuaded.

Stella and Lily risk everything for love and freedom as the brutal Civil War drags on. Their paths converge in New Orleans where, through an unexpected encounter, they discover that even the most delicate threads have the capacity to save us.

Review:

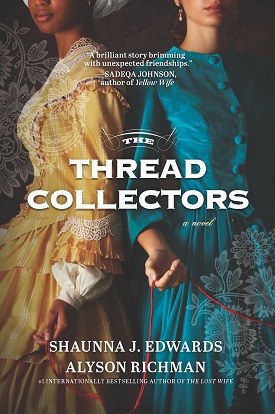

Alyson Richman earned a degree in art history and Japanese studies from Wellesley College and is the bestselling author of several historical fiction novels, including The Garden of Letters, The Velvet Hours, and The Lost Wife. She is also an accomplished painter and frequently weaves her love of art into her stories. She resides on Long Island, New York, with her husband and two children. Shaunna J. Edwards grew up in New Orleans, Louisiana, and graduated from Harvard College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in literature before continuing her education at New York University School of Law where she earned her Juris Doctor. She practiced corporate law before penning The Thread Collectors, her debut novel, with Richman. Committed to divesity, equity, and inclusion, she now lives with her husband in Harlem, New York.

The Thread Collectors is the product of a decades-long friendship between Richman and Edwards, a Black woman and Jewish woman who, proud of their heritages, “wanted to explore the Civil War experience through two underrepresented lenses and illuminate the important and often overlooked tragedies of the era.” They also set out to “show how ingenuity and creativity can bridge cultural divides and create power for the seemingly powerless.”

Inspiration for the story came from several sources, including a documentary, “Burying the Civil War Dead,” from which they learned that Black soldiers, who comprised ten percent of the Union Army, enlisted expecting to fight against slavery. Instead, they were often assigned to dig ditches in which white soldiers were buried and created maps designating the burial sites of Black soldiers. Additionally, some eight thousand Jewish men fought. Many of them were German and Hungarian immigrants who came to America to escape religious persecution only to encounter antisemitism and bigotry.

The character of Jacob Kling is based on a musician who enlisted in the 31st Regiment of New York. Having left his wife, Lily, a harpist, behind in New York, Jacob is stationed at Camp Parapet near Jefferson, Louisiana, assisting the doctor who is examining the many Black men who have arrived to serve with the Louisiana Native Guards. In the book, as in the life of Richman’s ancestor, Jacob’s older brother has enlisted in the 29th Regiment of Mississippi. Samuel left New York and established a mercantile emporium in Satartia, Mississippi. Samuel was dispatched by their father to expand the family’s trading business and, surprisingly, found a Jewish bride and settled there. The brothers’ opposing stances create tension, especially when Lily is unable to hide her feelings during a visit. She is appalled that Samuel would join the effort to maintain slavery, telling Eliza, Samuel’s wife, as they sit down to the Seder meal, “Tonight we celebrate family, but we also pay respect to the Israelites’ escape from bondage in Egypt, and yet you fail to see the irony of your words, in support of Southern slavery, dear sister.” Samuel insists that he had no choice and is fighting not to protect slavery, but to hold onto the business and home he has worked hard to establish. He believes that if the Rebel forces lose, his family will be destitute. The brothers’ affection for each other is never in question and both despair at the prospect that they could find themselves on opposite sides of a battlefield.

Stella was inspired, in part, by one of Edwards’s ancestors. Through her and her family members, Edwards wanted to “delve into how skin color and, in the case of William, musical talent afforded opportunities to some that would remain wholly unavailable to others.” As the story opens, Stella and William are saying good-bye to each other, unsure if they will ever be reunited. William is running away from New Orleans and his master, risking his life to join the Union Army at the enlistment camp ten miles away. William and Stella love each other but are not permitted to marry or even make decisions about their own lives. They believe that once the Union Army wins the war, that will change.

There, he meets Jacob and the physician Jacob is assisting, who is astounded that William does not bear the kind of physical scars that so many other enslaved men do and his hands have no calluses. William has never performed hard labor. His musical talent was discovered when he was just six years old and he was sent to live in the main house where he was forced to play the flute to amuse and entertain his master’s wife and their guests. He was required to dress in the hand-me-down suits of his master’s son and perform on command, which was demeaning. Although singled out for his musical prowess, he was denied the opportunity to learn to read music because reading is forbidden . . . and a punishable offense. William can express his feelings through his music, but lacks the ability to commit his thoughts and emotions to paper.

Stella lives in a Creole cottage with her half-sister, Ammanee. Their mother, Janie, lives nearby in her own cottage on Rampart Street. Their homes are furnished with cast-off items, and their masters provide them with meager allowances to buy food. They are among the light-skinned women who enjoy elevated living conditions because they have been granted favor by the white men who control their lives. Janie was separated from Ammanee’s father, the love of her life, and never saw him again, but given her “freedom papers” when Stella was fathered by her master. She is not free to leave, however. Mr. Percy permitted seven-year-old Ammanee to be her half-sister’s nursemaid and promised Janie that she could select the man who would be Stella’s master. Stella was “sent to market” when she was eighteen years old and it was there that she met William, playing his flute. Keeping his promise to Janie, Mr. Percy negotiated a deal with Mason Frye, William’s master, for Stella. She would be provided four bolts of fabric, ten spools of threat, three cotton slips and bloomers, two cast-iron pots, a copper kettle, a wooden desk, a chair, and a mirror. And most importantly, Ammanee would also be purchased to serve as Stella’s maid. The three women are fortunate to be together, but Stella is required to submit to her master’s demands and whims, and when, after William escapes, she realizes she is pregnant, worries what will happen if the child’s skin color is too dark to convince Frye that he is the father.

Stella is a skilled seamstress, of necessity, and after she embroiders a map to guide William, she is called upon by her neighbors to create maps for their sons and brothers who also plan to join the Union Army. She incorporates information gleaned by Ammanee from conversations she overhears while working in the nearby church. Because fabric and thread are precious commodities, quilts, purses, and petticoats must be repurposed, with thread being carefully extracted in order to be used again. Stella codes the maps in various colors signifying routes that are believed to be less fraught with danger than others.

As the war rages on, William is pressed into service, along with a young drummer boy who barely speaks, performing nightmarish tasks he could never have imagined. Teddy is just ten years old, and eventually reveals how he came to be completely alone in the world, his drum his only possession, and in a Union Army camp. William, in particular, is fond of and determined to protect him. Jacob wrote a beautiful song for Lily, “Girl of Fire,” and many of the soldiers have learned it. In the evenings, along with other musicians, Jacob, William, and Teddy bring comfort to and boost the morale of the men who are fighting.

They develop a strong sense of camaraderie through their music, as well as their individual senses of being “other than.” Jacob hides his background, painfully aware that many of the men he encounters have never before met a Jew and not all will accept him. “The men in his infantry had always kept him at arm’s distance. They were mostly polite and cordial, but the feeling of being an outsider was still hard to shake.” William stands apart from many of the other men who have endured harsh physical conditions their entire lives. But William is no stranger to hardship and heartbreak, having watched his mother suffer.

A holiday cease-fire inspires William to enlist Jacob’s assistance to make it special for young Teddy. But their trek into the nearby woods ends tragically and tests the bonds the men have formed. With no idea what is happening to William or even if he is still alive, Ammanee and Stella will do whatever is necessary in order to keep Stella’s child safe. When weeks pass with no word from Jacob, Lily is overcome with worry and determined to find him. But journeying from New York into the South is extremely dangerous, especially for a woman traveling alone, and there are no registries in which the names of soldiers are logged, nor do the various military hospitals maintain records of their patients. Lily’s father in unable to convince her to remain at home and wait for word about Jacob’s whereabouts and condition, and she embarks on a treacherous trip to Samuel’s home. She is shocked when she arrives and see what has become of Samuel and his family. She begins visiting hospitals in search of her husband. There, she witnesses and begins to appreciate the horrifying effects of war as she walks among the wounded and near-dead, hoping to find Jacob among them. She spent months stitching quilts and rolling bandages to send to the very hospitals in which she was now searching for her husband, but “seeing firsthand the pain and hopelessness in each man’s face made her realize that the human suffering of this war could never truly be comprehended by someone far away in New York. She had imagined it would be terrible, but reality was so much worse.”

The Thread Collectors is a sprawling, engrossing story featuring compelling and fully developed characters. Edwards and Richman illustrate the various ways in which their Black characters enjoy better living conditions than many of their contemporaries. Yet, despite those advantages, they are not free. They are still enslaved. Even if they do not bear physical scars inflicted through mistreatment and back-breaking labor, they are emotionally scarred as a result of seeing loved ones abused and ripped away, and being confined and controlled, deprived autonomy even over their own bodies. But they are hopeful, believing that the Union Army will prevail and they will at last be free to live their lives on their own terms.

They are each, in their own ways, resilient and resourceful, resorting to drastic measures, if required, in order to survive. Jacob and Lily are earnest and endearing, but unprepared for the harsh realities of war. Edwards and Richman use the letters they write to each other not only to advance the story, but also provide insight into their feelings, especially concerning the ideological division that threatens the Kling brothers’ relationship.

As the fast-paced and inventive story proceeds, Edwards and Richman cleverly pull together the various storyline threads. Lily, Stella, and Ammenee are tenacious and brave. Eventually, Lily and Stella come face to face and learn about the unlikely friendship between Jacob and William, men of quiet integrity and honor, that is convincingly depicted. Initially because of their mutual love of music, but ultimately because of the atrocities of war, Jacob and William find commonality, and mutual respect and admiration for each other.

The Thread Collectors is the story of unbreakable bonds of family and love for those we choose to be our family members. It is also an illustrationg of the inherent strain in the mother-daughter relationship between Janie, a woman who has survived unspeakable heartbreak and views the world in a pragmatic, realistic manner, and Stella, who is initially idealistic and naive, but quickly matures when she becomes a mother who will do anything to protect her child.

The Thread Collectors is a unique and absorbing work of historical fiction about the most harrowing period in America history that is also timely and contemporary. Edwards and Richman penned the book in 2020, “as the world wrestled with growing awareness of racialized violence and inequality,” in an effort to combine their creative “energy to find beauty in that darkness.” They have indeed crafted a beautifully memorable story that continues to resonate long after reading the last page of the book.

Excerpt from The Thread Collectors

PART ONE

New Orleans, Louisiana

March 1863

She opens the door to the Creole cottage just wide enough to ensure it is truly him. Outside, the pale moon is high in the sky, illuminating only half of William’s face. Stella reaches for his sleeve and pulls him inside.

He is dressed to run. He wears his good clothes, but has chosen his attire thoughtfully, ensuring the colors will camouflage in the wilderness that immediately surrounds the city. In his hand, he clasps a brown canvas case. They have only spoken in whispers during their clandestine meetings about his desire to fight. To f lee. The city of New Orleans teeters on the precipice of chaos, barely contained by the Union forces occupying the streets. Homes abandoned. Businesses boarded up. Stella’s master comes back from the front every six weeks, each time seeming more battered, bitter and restless than the last.

William sets down his bag and draws Stella close into his chest, his heartbeat accelerating. He lifts a single, slim finger, slowly tracing the contours of her face, trying to memorize her one last time.

“You stay here, no matter what…” he murmurs into her ear. “You must keep safe. And for a woman like you, better to hide and stay unseen than venture out there.”

In the shadows, he sees her eyes shimmer. But she balances the tears from falling, an art she had been taught long ago—when she learned that survival, not happiness, was the real prize.

Stella slips momentarily from William’s arms. She tiptoes toward a small wooden chest. From the top drawer, she retrieves a delicate handkerchief with a single violet embroidered in its center. With materials in the city now so scarce, she has had to use the dark blue thread from her skirt’s hem to stitch the tiny flower on a swatch of white cotton cut from her petticoat.

“So you know you’re never alone out there,” she says as she closes William’s fingers around the kerchief.

He has brought something for her, too. A small speckled cowrie shell that he slips from a worn indigo-colored pouch. The shell and its cotton purse are his two most sacred possessions in the world. He puts the pouch, now empty, back into his pocket.

“I’ll be coming back for that, Stella.” William smiles as he looks down at the talisman in his beloved’s hand. “And for you, too… Everything will be different soon.”

She nods, takes the shell and feels its smooth lip against her palm. There was a time such cowries were used as a form of currency for their people, shells threaded on pieces of string exchanged for precious goods. Now this shell is both worthless and priceless as it’s exchanged for safekeeping between the lovers.

There is no clock in her small home. William, too, wears no watch. Yet both of them know they have already tarried too long. He must set out before there is even a trace of sunlight and, even then, his journey will be fraught with danger.

“Go, William,” she says, pushing him out the door. Her heart breaks, knowing the only protection she can offer him is a simple handkerchief. Her love stitched into it by her hand.

He leaves as stealthily as he arrived, a whisper in the night. Stella falls back into the shadows of her cottage. She treads silently toward her bedroom, hoping to wrap herself tightly in the folds of the quilt that brings her so much comfort.

“You alright?” A soft sound emerges in the dark.

“Ammanee?” Stella’s voice breaks as she says the woman’s name.

“Yes, I’m here.” Ammanee enters the room, her face brightened by a small wax candle in her grip.

In the golden light, she sits down on the bed and reaches for Stella’s hand still clutching the tiny shell, which leaves a deep imprint in her palm.

“Willie strong,” Ammanee says over and over again. “He gon’ make it. I know.”

Stella doesn’t answer. A flicker of pain stabs her from the inside, and she finally allows her tears to run.

———-

PART TWO

May 30, 1863

Port Hudson, Louisiana

Dearest Lily,

I am sorry it has been so many days since my last letter to you, but it has been impossible to find the calm I need to write. Even as I clasp my pen, trying to find the right words to relay to you, my dearest love, I must reach for the blanket you sent me and find comfort in those white stars you stitched to pull me out from this darkness. I have seen so much bloodshed in the past few weeks, and it has left me badly shaken.

I fear that I have not known the horrors of war until now. Camp Parapet was a lazy haven compared to the inferno of Port Hudson. Just three days ago, the stretches of green grass were covered in more blood, more limbs than one could have ever conjured in their worst nightmare. The fields that stretch beyond my campsite, toward the mouth of the river, are still filled with the dead.

We were not expecting the Rebs—who we outnumbered by the thousands—to have put up such a fight! And for the first time, General Banks agreed to give rifles to all the valiant Black soldiers in the Louisiana Native Guard, to see just how committed they were to fighting for their freedom.

I don’t believe any of us could have anticipated the bravery that ensued, my dearest love. As my own regiment lay waiting in the outer banks, they sent the Native Guard in first, led by one of their own. This brave lieutenant, André Cailloux, I’m told, steered the charge, calling out to his men, both in English and French, “Let us go forward!” He continued to battle forth, even after he was struck by a mini-cannonball that tore through his flesh. And even then he would not be silenced in his urgent call to drive his comrades, until he received one final blow.

I weep as I write this, for the fields are still littered with the corpses of hundreds of Black men along the north front of the Mississippi River, Cailloux’s and countless others. But the parties have still made no call for a truce, and who knows how long these brave soldiers must lay there without the cover of earth and a proper burial befitting such noble men. I fear it was a needless sacrifice, ordered by men who had not taken the time to understand the enemy’s superior position, and careless with the lives of men they do not consider their equal.

I am heartbroken and worried for my musician friend, William, and the little drummer boy who is always at his side, for they are part of the Third Guard. Do pray for them, as I know your prayers continue to keep me safe.

Your loving husband,

Jacob

July 18, 1863

New York City

My darling Jacob,

I am not sure if news of what happened here in New York will have reached you by the time you receive this letter. Even now, as I write to you, my heart is heavy beyond measure. In your last letter, you shared how deeply affected you were by witnessing the horror of what your friend William and his regiment endured. And now I find myself, like you, bearing witness to a horrendous torrent of cruelty against innocent men, women and children.

For five days, Manhattan has been on fire, with angry mobs rioting and causing terrible wreckage and chaos. The unrest was sparked by the new conscription laws; men were irate that their names could be pulled from a barrel to meet our noble president’s call for 300,000 more able bodies to join the fight. But never could I have imagined the hatred that teemed beneath the architecture of our great city, the festering evil of men who were enraged by the possibility of being forced to fight in what they called “a nigger war.”

The self-proclaimed “protesters” began their destruction on Monday, just two days after the marshal drew out the first batch of names. They stormed the draft headquarters on 46th Street and Third Avenue, throwing rocks and bricks through windows and beating any policemen who stood in their way. They smashed the draft barrel, scattered the name cards throughout the floor and then set the building on fire.

But the worst was still to come, dearest husband. They then unleashed their wrath onto nearby colored families and businesses. Jacob, they pulled men from their homes, beating them relentlessly, and eleven men were lynched.

And then, as if the nightmares would never cease, these rioters committed even more unspeakable acts! They attacked the venerable Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue, which houses dozens of orphans. I’ve been informed by ladies of the Sanitary Commission sewing circle that the children there are the sons and daughters of Negro soldiers who are either off fighting, or had been killed when they joined the Union ranks.

These poor orphans were sitting quietly at their desks when hundreds of men, women and even youngsters, stormed the building armed with bricks, clubs and bats. Miss Rose told me she heard from someone who witnessed the attack that the men were crying “Burn the niggers’ nest!”

I am sorry that I am detailing all of this horror to you in a letter. Perhaps it would have been better served remaining within the pages of a journal. But the only solace I can find after learning of such wickedness and heinous prejudice is to take comfort that I am married to a man who fights on the side of justice and equality. Know that you are not alone. The rioters might have defaced our newspaper headquarters with the words, “Death to the Lincolnites!”, but we women will not be dissuaded from joining the fight in any way we can.

Please write and reassure me you are safe and without injury. The mail has been frightfully slow, and I continue to worry about your health.

You must come home to me, my darling man. I miss you. Tomorrow I will join some of the women from the Sanitary Commission. With the summer heat now in full swing, we’ve decided to postpone our quilting activities (it’s far too warm to send you all blankets!) but, instead, we will continue to spend our hours preparing and rolling bandages. I hope these pieces of gauzy white are never used to wrap any of your limbs, and that only my quilt should keep you in a tight embrace when it becomes cool again.

I adore you and pray for better times.

Your devoted and loving wife,

Lily

Comments are closed.