Synopsis:

Synopsis:

First Rule: Make them like you.

Second Rule: Make them need you.

Third Rule: Make them pay.

They think I’m a young, idealistic law student. That I’m passionate about reforming a corrupt and brutal system.

They think I’m working hard to impress them.

They think I’m here to save an innocent man on death row.

They’re wrong. I’m going to bury him.

Review:

Author Dervla McTiernan practiced law for twelve years in Ireland. But after weathering the 2007 global economic crisis, she and her husband, an engineer, moved to Perth, Australia, in search of a fresh start. There, she says they have built a better life than they ever could have hoped for.

McTiernan describes her transition to being a published author as “dramatic.” She began writing every night while working for the Civil Rights Commission. Although she had completed her first book, she had been suffering from headaches and consulted her physician who, shockingly, informed her she had a brain tumor. Having just received that news, she was sitting in her car preparing to make an appointment with a neurosurgeon. At that very moment, she received an email from the agent in New York City to whom she had sent the first fifty pages of her manuscript. The agent wanted to read the rest of the book. Arriving at home, McTiernan literally told her husband, “I’ve got good news and bad news.” Just four weeks after undergoing successful surgery, she secured an agent. And shortly after that, publication offers began rolling in. Her first book, The Ruin, launched her three-volume Detective Cormac Reilly series and was a top ten bestseller; the second installment, The Scholar, was a top five bestseller; and the third book in the series, The Good Turn, went to the top of the bestseller list. McTiernan’s work has been shortlisted for the Barry, Kate O’Brien, Australian Book Industry, Irish Book, and Western Australian Premier Book Awards. And most importantly, she is healthy.

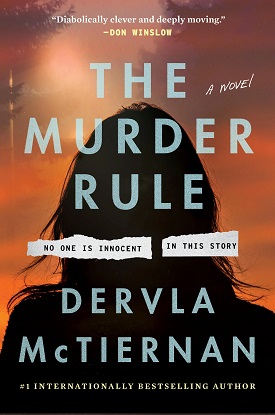

The Murder Rule, her first stand-alone novel, was inspired by a newspaper article McTiernan read several years ago about a young Irish law student who came to the United States to volunteer with the Innocence Project for one summer. The Innocence Project was founded by law professors Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, who, in 1988, began studying and litigating issues surrounding the use of forensic DNA testing. Their groundbreaking work provided the foundation for state and federal legislation establishing standards governing the use of DNA testing in legal cases, and changed the way in which criminal investigations and prosecutions are handled. Returning to Ireland, that young student could not forget about one of the cases she worked on, and continued searching for answers. Eventually, with the assistance of a retired police officer, she uncovered the evidence that proved the convicted man’s innocence.

Digging deeper into the story, McTiernan learned that the exoneration took more than five years, and the man served twenty-six years of a twenty-nine-year sentence for a crime he did not commit. Those revelations caused her to ponder the public relations considerations of an organization like the Innocence Project. She wondered why that dark and very important aspect of the story was not emphasized in the original reporting. Acknowledging that it could be because the media chose to play up the inspirational component of the tale, McTiernan began imagining what might happen if the information supplied to the press was carefully curated and controlled by organizational spokespersons. And if so, she asked herself, “Would I blame them?” That gave McTiernan the idea to “invert” the story. A young, enthusiastic law student worked diligently to help the organization fulfill its mission, but McTiernan found herself contemplating what could happen if the opposite were true. What if the law student deliberately set out to sabotage the organization’s efforts?”

The Murder Rule is the story of Hannah Rokeby, a third-year law student in Maine. McTiernan says that Hannah, “at first glance, appears to be exactly what you’d expect — bright-eyed, eager to impress her professors, and wanting to change the world.” Indeed, from the outset, McTiernan establishes that Hannah is confident, bright, self-reliant, and tenacious. But the book opens with a series of emails Hannah exchanges with Robert Parekh, an associate professor at the University of Virginia School of Law and Director of the Innocence Project Clinic. Just two weeks earlier, Hannah stumbled upon an article in Vanity Fair “and found out exactly what was happening at the University of Virginia.” She quickly formulated a plan and sets it in motion. Hannah acknowledges that the window to apply to volunteer at the clinic has closed, but presses Parekh to give her a position by mentioning the “personal mentoring” Parekh allegedly provided her friend. A few days later, Hannah sneaks out of the home she shares with Laura, her alcoholic mother, taking with her “a small, battered notebook with a faded red cover” — her mother’s diary — and makes her way to the modest apartment she sublet at the last minute in Virginia. Hannah first read her mother’s journal when she was just fourteen years old. The entries date back to 1994 when Laura was nineteen years old. Confessing that she read it brought Hannah and Laura closer, and Hannah believes that the diary truthfully recounts what happened to Laura and who was responsible.

Hannah concocts a story about her mother’s participation in a three-month clinical trial at a Charlottesville hospital which necessitated her transfer from the University of Maine School of Law. Parekh is not rattled by Hannah’s attempted blackmail, but is intrigued by her drive, so he offers her the chance to join a group of three or four other students working a minimum of fifteen hours per week. She is not immediately assigned to the Michael Dandridge death row case — the impetus for her move to Virginia. Rather, she is assigned to review and evaluate applications for assistance received from inmates. But not for long.

In April 2008, Dandridge was convicted of raping and murdering Sarah Fitzhugh in June 2007, and sentenced to death. All of his appeals were procedurally barred or rejected on the merits. In November 2018, he applied for assistance from the Innocence Project. Parekh believed Dandridge’s claim that the sheriff beat him up and threatened him until, under duress, he confessed to the crime. Dandridge also insisted that he informed both his trial and appellate attorneys, neither of whom raised the issue in court. An investigation revealed that exculpatory evidence was wrongfully withheld from Dandridge’s trial attorney by the prosecutor. Thus, after eleven years on death row, his conviction was overturned and he is about to stand trial again. A preliminary hearing is set for the following week. Hannah knows she has to move quickly and use any means available to get herself assigned to the Dandridge defense team. And she does.

McTiernan alternates chapters moving Hannah’s story forward with Laura’s diary entries. In the first one, Laura explains that she is working as a housekeeper at a hotel near Seal Harbor on Mount Desert Island, Maine, because she wanted to get away from Boston for the summer. She picked up a side job cleaning a house which turned out to be a frightening experience. There were two guys there and while cleaning, she discovered cocaine, as well as a semiautomatic pistol. And overheard one of the guys — Mike — having a heated argument with his mother on the telephone. She also witnessed Mike trying to convince the other guy, Tom Spencer, to take a trip with him to Canada. She unequivocally declares that she has no intention of getting caught up in whatever drama was playing out in that home. Subsequent journal entries detail that she did not stay true to her conviction, along with events surrounding Tom’s death.

Gradually, Hannah’s real motivation for moving to Virginia and worming her way onto Dandridge’s defense team is revealed, and it is anything but altruistic. In reality, she is determined to see that Dandridge remains in prison. Based on her mother’s diary entries, Hannah believes that Dandridge raped Laura and brought about her father’s death. She has always been led to believe that her father came from a rich family who paid her mother off because they did not want her to have anything to do with him, and he died before Hannah was born. “Under the surface, she’s actually pretty ruthless, and working for her own agenda,” McTiernan explains. Indeed, McTiernan illustrates how shrewd and calculating, and wiling to cross legal, moral, and ethic boundaries Hannah is. But Hannah believes strongly in what she is doing and that her actions are in pursuit of a greater good. McTiernan manages to make Hannah surprisingly likable and empathetic, even as it is clear that she is being dishonest and seeking to infiltrate the Innocence Project in order to derail its efforts to see Dandridge exonerated. She comes close to being an anti-hero until readers recognize that if she possesses evidence of Dandridge’s guilt — irrespective of whether his confession was coerced — she has an ethical and moral responsibility to disclose it to her colleagues. McTiernan describes her as “quite uncompromising” and notes that her unwavering commitment to her goal is “where she goes wrong.” Indeed, as the story proceeds, Hannah and readers learn that she has taken action and set things in motion in reliance upon faulty perceptions and conclusions. Eventually, she is forced to recognize and accept the truth, and deal with the consequences of her actions, which are not what she envisioned or desired. That is extremely unsettling and difficult for her.

The book’s title is derived from the felony murder rule. Criminal laws generally require that a defendant possess the specific intent to commit the crime with which he/she is charged. The felony murder rule is an exception, holding that if a death occurs during the commission of a felony, the defendant can be convicted of murder despite having no plan or intent to bring about the death. Thus, the felony murder rule flies in the face of the idea that a criminal defendant can be held responsible only for the outcome he/she foresaw when deciding to engage in criminal conduct. McTiernan felt the title fit the book because she explores whether “Hannah is responsible for all of the outcomes of her actions. How about if she didn’t foresee something happening? What if she should have foreseen it had she done the work?”

It’s about narrative, isn’t it? We love a story. We want a hero. We want a bad guy. We want a beginning, a middle, and an end. And life is more complicated than that but we love it when we’re served up a story and sometimes if we don’t get it, we make it up for ourselves. We believe only the facts that suit the story we like and we ignore everything else.

The Murder Rule examines each character’s motivations for his/her choices and actions, and questions their justifications. McTiernan’s characters are fully developed and intriguing. As noted, Hannah is young and quixotic, her machinations fueled by years of ruminating on erroneous beliefs. Laura is an alcoholic and, unsurprisingly, manipulative. McTiernan’s use of the dual narratives is highly effective because readers get to know Laura, through her old journal entries, along with Hannah who documents her present-day activities and interactions. Readers also learn the truth, along with Hannah, and are privy to her emotional journey as she realizes that the indisputable evidence does not square with her mother’s account of events. The tale is a compelling examination of the mother-daughter relationship between Laura and Hannah — two women with divergent goals. Laura wants to keep the past hidden and put it behind her while Hannah is on a quest for truth and a specific brand of justice. What will Hannah due when the truth is fully revealed?

Because McTiernan practiced law, she injects credible details about the legal aspects of the story, including a tensely climatic courtroom scene, while requiring some suspension of disbelief from her readers. Putting those flaws in the tale aside, it is a fast-paced, otherwise tautly-crafted, and entertaining thriller replete with shocking revelations and surprising developments. McTiernan’s overarching story is clever, as the eventual unveiling of the connection between Tom’s death and Dandridge’s case demonstrates. It is also an absorbing exploration of a dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship and its impact on Hannah.

The Murder Rule is an engrossing meditation on under what circumstances, if any, questionable means can ever justify the achievement of a desired end. McTiernan says she wanted to explore a highly provocative question: “What if you’re a good person trying to do good things in a world that doesn’t seem to care? And the world we live in right now doesn’t seem to care. Would you take a little step off the ethical path in order to be effective?” And if one does that, what about another little step. And another. And another . . . “How far would you go? Where does that line sit? Because it’s very hard to be effective in the world today if you follow the rules strictly.” It’s up to readers to decide if they accept McTiernan’s core premise, whether Hannah is that good person McTiernan references, and if wrongful actions by police, prosecutors, or others can justify the means employed to write those wrongs. And what they might do if forced to confront similar circumstances.

Excerpt from The Murder Rule

One

Hannah

Saturday, August 24, 2019

The night before she left for law school, Hannah Rokeby didn’t sleep. She went to bed early and listened to the sounds her mother made as she moved about the house. Their home in Orono wasn’t small, but it was old, and sound traveled. Hannah heard the clatter of dishes from the kitchen, the opening and closing of cupboard doors, Laura’s footsteps as she moved into the living room, then silence. No television, but that made sense, because Laura would likely be reading. At eleven-thirty P.M., when the creak of floorboards signaled that Laura was finally climbing the stairs to go to bed, Hannah closed her eyes and concentrated on her breathing, making sure that it was slow and even. Her bedroom door opened. Laura entered the room, came over, and sat on the bed. Hannah could smell her mother’s perfume—jasmine and cedar. She tried not to flinch as Laura stroked her forehead, once, twice, three times.

“My darling.” Laura’s voice was soft, not much more than a whisper. Hannah kept her eyes closed. Breathed in, and out. A minute passed. Laura was very still, so still that Hannah’s mind started to play tricks on her. Could she still feel the weight of her mother’s hand where it rested against her lower back, outside the blankets? Still feel the slight tilt in the mattress caused by Laura’s position on the bed? Hannah resisted the urge to open her eyes. Laura liked to talk and Hannah couldn’t bear that, not tonight. Another long moment passed before Laura sighed, and finally rose. She left the room, closing the door behind her, and Hannah opened her eyes. She reached for her phone and checked the time. She set a silent alarm, closed her eyes again, and tried, unsuccessfully, to sleep.

At four A.M. Hannah got out of bed, opened her closet, and took out her large backpack and her shoulder bag. The backpack was already packed. She filled her shoulder bag with those small essentials she hadn’t been able to pack without prompting questions from Laura that she wasn’t ready to answer. Her hairbrush, toothbrush, and her small bag of makeup and toiletries. The copy of Vanity Fair, hidden under her pillow, that had started all of this. A couple of textbooks—Charles O’Hara’s book on criminal investigation, and another on forensic and criminal psychology. Legal pads and a few pens. Hannah hesitated. There was something she was forgetting, something important. Memory returned and she took two quick steps to her nightstand and drew out a small, battered notebook with a faded red cover. She held the notebook between her hands for a moment, drawing strength from it, then carefully tucked it between the textbooks in her shoulder bag. It would be safe there.

Hannah turned off her bedside lamp and left the room. The house was very dark. What light there was came from Laura’s bedroom; her door was open. Hannah set her bags down gently and crept forward. A floorboard creaked and she flinched. She waited a moment, then leaned against the doorjamb of her mother’s room and peered inside. Laura was sound asleep. She had left her blinds open and moonlight streamed in across her bed. She looked beautiful, but that was to be expected. Laura always looked beautiful. In her early forties, she was still slim and blond with fine features and an air of fragility that seemed to attract the wrong kinds of men. It was only in sleep that that fragility — expressed by a slight tightness in the set of her lips, a suggestion of strain in her eyes—faded away and she looked like she should. As if nothing had ever hurt her.

Hannah pulled the door slowly closed. There was no creak from the hinges, because she had oiled them the day before. She went downstairs, took a folded note from her backpack, and placed it so that it was held in place by the coffee machine. Okay. Almost there. Hannah went to the laundry room. There was an extra freezer there that they used to store frozen vegetables and ice cream. She opened the door and pushed aside the bags of frozen peas that covered her stash. For the past two weeks she had made extra portions of the meals she prepared for lunch and dinner, boxed and labeled them, and stored them here, where she could be sure Laura wouldn’t find them. Using the light from her phone as a flashlight, Hannah chose a portion of quiche and another of shepherd’s pie and carried them back to the kitchen fridge, where Laura would see them.

Everything was in place. It was time to go.

Except . . . damnit . . . should she search? One last time before she left? Hannah was torn—on the one hand, searching was a betrayal of Laura’s trust (she had promised); on the other, it would be irresponsible not to, right? Hannah looked at her watch and grimaced. She had time, barely. And she could do it quickly, run through the usual places. First the water bottles in the fridge. Check the seals, make sure they haven’t been opened. Then run a hand behind the books on the shelves in the living room. Next lift the couch cushions, then look inside the ficus planter in the corner, then the water tank in the downstairs bathroom. She found nothing. Hannah’s spirits lifted. Where else? Laura’s tennis bag—it was hanging on the end of the stairs and there was a plastic water bottle tucked in the outside pocket. Hannah opened the bottle and sniffed. Water. She was being silly. This was a delaying tactic because she was afraid to leave. Pathetic. Enough. Time to go.

Unlocking the front door meant undoing the chain and the dead bolt. There was no way to close them all again from the outside, but it was only a couple of hours to dawn now. Laura would be fine, Hannah told herself. Laura would be fine. The air was cool and clear, and there was an Uber idling out front, lights on. Hannah hurried down the drive, put her backpack in the trunk, and climbed into the car. The driver was a hulking shadow in the darkness.

“When I booked you, I left instructions to wait down the street,” Hannah said.

He shrugged his indifference. His eyes met hers briefly in the rearview mirror. “The airport?”

“Yes.”

The car pulled slowly away from the curb and Hannah looked back at the house.

“Wait.”

“What?”

“Just give me a second.” Hannah was out of the car before he’d come to a complete stop. She ran to the trash cans that were lined up neatly to one side of the garage. She opened the recycling can. It was full of empty milk cartons and yogurt containers, with cardboard packaging neatly folded on top. Hannah rummaged through everything, telling herself all the time that this was crazy, that she was being paranoid, and yet feeling nothing but a sense of inevitability when her hand closed around a bottle that wasn’t empty at all. She drew out a full bottle of Grey Goose, then another. She searched again, but that was it. Goddamnit. What did this mean? The bottles were full. But . . . at least they hadn’t been opened. That was a good sign. Laura might have bought them, but she hadn’t had a drink. So far, at least, she had kept her promise. Hannah opened the bottles, poured the vodka into the lawn, and put the empty bottles back into the recycling can. Then she ran back to the cab.

“Everything okay?” the driver asked. She could see his eyes again in the rearview mirror, assessing, curious.

“Fine.”

He drove on through dark and empty streets, and they didn’t speak. Hannah looked out of the window, watched the houses as they passed, saw the occasional light come on as early risers started their day. She thought of Laura, waking alone to a dark house.

———-

Hannah’s flight landed at Dulles at ten-thirty A.M. At eleven-thirty she boarded a bus. She fell asleep almost before the bus left the station and slept on and off all the way to Virginia. The bus pulled into Charlottesville just before one P.M. and she got off, feeling groggy, headachy, and hungry. She hesitated, then turned on her phone. She had six missed calls from Laura and three text messages. Hannah ignored the calls and the messages and instead used her maps app for directions. The place she’d rented was less than a mile from the station. She grimaced as she thought about calling an Uber. She couldn’t face small talk, and maybe some fresh air would make her feel better. Besides, a walk would give her a chance to check out a little bit of Charlottesville. She set off, and was just beginning to regret her decision when she reached the apartment building. Hannah checked out the three-story building and let out a sigh of relief. She’d expected a dump. When you book the very last rental available the week before classes start, that’s almost what you deserve. But so far, so good. According to her maps app, the building was only a five-minute walk from the law school, as promised. The paint was clean and bright. There was even a little yard out front, pretty and well-maintained. Hannah made for the entrance and pressed the buzzer for apartment 5B. A few moments later a slightly distorted voice came through the speaker.

“Yes?”

“Yes, hi. I’m Hannah Rokeby. I’m looking for David Lee?”

There was a moment’s silence. “Uh . . . yeah? This is David.”

“I’m subletting Prisha Laghari’s place this semester. She said you’d have the keys.”

“Oh yeah, right. Sorry. I’ll be right down. Just two minutes.”

It was closer to seven minutes before David appeared. He was a good-looking guy, sloppily dressed in jeans and an oversize T-shirt. He pulled the front door open and gestured for Hannah to come inside. He had the smudged remains of eyeliner around his eyes.

“Sorry,” he said. “It took me a minute to find them.” He held up a key ring, a stainless-steel dolphin with two keys and a swipe card attached. “Prisha’s place is on the third floor. I’ll show you.” He led the way toward the elevator. Hannah followed. She had her backpack on her back, her shoulder bag dangling from her right hand.

“You travel light,” David said. “You should have seen me yesterday. My parents took my Mom’s minivan, and I drove my car and we could barely fit in all my stuff. But I play keyboard, you know, and guitar. With my amps too it takes up a lot of space.”

“Right,” Hannah said.

“I’m in a band.” He looked at Hannah with an air of expectation. It was clear that he wanted her to ask him about his music, his gigs; maybe even ask him for coffee to talk about it. Hannah stared back at him blankly. She wasn’t there to make friends. They rode up in the elevator in an awkward silence, arrived on the fifth floor, and he led the way down the corridor. Inside, the building was bright and modern, the carpet very clean and the paintwork fresh.

David stopped outside apartment 5B and held out the keys.

“This is you,” he said. “See you around.”

“Thanks.”

He left, and Hannah turned and unlocked the door to 5B. She walked inside, dropped her bag on the ground, and shut the door behind her. The apartment was . . . great. It was a studio. It had high ceilings and two large windows that let in a lot of light. There were bookshelves, still half-full, and a kitchenette built against the wall to the left. There was a double bed against one wall, its mattress bare. Suddenly everything felt strikingly unreal. Like she’d just taken a step into someone else’s life. Hannah crossed the room and sat on the bed, then sank back, pulled a pillow toward her and pressed it to her face. What was she doing? Was this crazy?

Ever since she had stumbled across the Vanity Fair article two weeks ago and found out exactly what was happening at the University of Virginia, she’d been too caught up in the frantic forward momentum of her plan to have time to think. Except, no . . . that was bullshit. She’d had plenty of time to think, she just hadn’t allowed herself to. And now she was in Charlottesville, at the point of no return. It wasn’t too late. She could still leave, take her bags, head back to Maine. Except . . . she’d be going back to what? More of the same? No chance for change, for things to really, truly, get better?

No. No way. She was here for a reason and no way was she going to chicken out before she’d even gotten started.

Hannah

Two

Sunday, August 25, 2019

Hannah unpacked, showered, dressed, then grabbed her jacket and decided to explore the campus. The law school offices probably wouldn’t be open, but she could figure out where everything was, save time later. And it was a beautiful day, better to be outside. The sun was shining and the sidewalks were busy with students. Classes started tomorrow, and most students had already moved in, but a few stragglers were still arriving. There were students out jogging, others lugging mattresses into apartment buildings, and more just walking with friends, coffee cups in hand. Hannah yawned widely. Coffee. That was an idea. She bought a cappuccino from a friendly girl at a café where the speakers played Tracy Chapman, and fought the urge to sit there for the day.

The offices of the Innocence Project were in the law school building, which was a five-minute walk from the apartment. The law school was set among trees, with a beautifully manicured lawn in the front. The building itself—built in redbrick and perfectly symmetrical—was modern and attractive and could not have been more different from the law school building at the University of Maine, which had been designed in the brutalist style, and had the dubious distinction of making an Architectural Digest list of the eight ugliest buildings in the United States. Hannah climbed the steps to the entrance hall and pushed open heavy double doors. She expected to find a security desk, an ID check at least, but there was nothing. Just a large, empty hall and wide corridors leading to the left and right. Hannah followed the sign that told her student services and clinics could be found in Slaughter Hall. This part of the building was older, a little more worn, a little more functional than the grand entrance hall.

She found the offices on the first floor after wandering for ten minutes. A simple door, with the words Innocence Project—Prof. R. Parekh stenciled on the glass. It was Sunday. The place was likely empty, the office locked up. Still, Hannah put her hand on the door and pushed gently. It opened. She stepped inside. The office was unremarkable, and Hannah let out a breath, feeling something between disappointment and relief. What had she been expecting, exactly? It looked just like any other midlevel corporate office. A large, open-plan space with a reception desk and behind that, multiple coworking desks and cubicles. There were three doors against the wall to the right that presumably led to other offices or meeting rooms. The place seemed deserted, except that the door to one of the private offices was open, and there was a light on inside.

“Hello?” Hannah said. A man emerged from the open office door. He was lean and handsome and she recognized him from the Vanity Fair article. Robert Parekh, Professor.

“Can I help you?” he said.

“I’m Hannah. Hannah Rokeby. You said to come and see you when I arrived on campus. I can come back tomorrow . . .”

“Grounds,” he said.

“Sorry?”

“We call it grounds, here. Not campus.” He shook his head. “It’s not important. Come in, come in.” He stepped forward and opened the little half-gate to the left of reception, ushering her inside. “I wasn’t expecting to see you today, but actually, your timing is quite good.” She followed him through to his office. His accent was British and very clipped. He sounded like one of the royal princes, which made sense, given his background.

The article in Vanity Fair had sold itself like a social justice piece, with multiple references to the Project’s work on behalf of death row prisoners, but the article—which was four pages long—had included a full-page photograph of Parekh. He’d worn a navy silk shirt with the top two buttons undone and had stared straight into the camera with a look that suggested both deep thinking and a hint of impatience. The headline had read Robert Parekh: The Next Caped Crusader? Parekh was a very good-looking man. The journalist who’d interviewed him had clearly been impressed—the tone of the piece had been almost fawning and the article had included lots of unnecessary detail about Parekh’s wealthy family, his years at Eton playing polo with royalty, and his relationships with beautiful, high-profile women.

Parekh took his seat behind his desk and Hannah sat too, folding her hands in her lap. For a long, disconcerting moment, he just looked at her. Hannah’s stomach tightened. She tried to read his expression. Given the way he’d responded to her email, she’d assumed this meeting would start with tension and excuses or denial and recrimination. But he was so calm, so in control that it was hard to imagine that he was in any way worried about her not very veiled threat to share what she knew about his relationship with his former student Annabel Bancroft.

Annabel was a law student, a part-time model, and a friend of Hannah’s friend Millie. Hannah and Millie had been undergrads together in Maine. When Hannah had called Millie—who had just graduated from UVA law—to ask a few discreet questions about Parekh, Millie had been happy to share the gossip about Annabel. That she’d had a short-lived, wildly passionate affair with Parekh. Which meant a potential scandal, something that could be used, maybe. But Hannah didn’t know Annabel personally, had never spoken to her, and Millie had said that the relationship was over and that Annabel only had good things to say about her ex. And now Parekh was so calm, so unbothered by Hannah’s presence, so it looked like he wasn’t worried. If that was the case, why had he agreed to see her? Maybe this wasn’t an interview. Maybe he was about to give her a verbal kicking and throw her out of his office. Hannah clenched her fists. That absolutely couldn’t happen.

Parekh picked up a thin file from his desk, opened it, and sorted through the papers within. “Yes. Here you are. Hannah Rokeby. University of Maine for undergraduate and law school. I assume that choice was driven by personal circumstances. Your transcript suggests you were capable of better.”

His snobbery irritated her but she didn’t allow it to show. “My mother needed me. It made sense for me to live at home while going to school.”

He nodded, but waited, eyebrows raised, as if her answer had been incomplete.

“My mother has cancer. She’s taking part in a clinical trial at University Hospital here in Charlottesville for the next three months. She’s staying in special housing close to the hospital, so I can’t live with her, but I thought coming to UVA for a semester would be a good way to stay close enough that she can call on me if she needs me. I can more easily spend weekends with her.”

“Yes,” he said. “That was in your email. And of course, it’s an opportunity for you too. To get a taste of the kind of education that perhaps you should have had.”

His eyes were sharp. Hannah suppressed the urge to defend her school and her professors.

“That’s true.” She cleared her throat, pressed forward. “I have excellent research skills. During my summers I volunteered at the Maine State Free Legal Advice Clinics, so I have experience working directly with clients. The clinics were very busy, so I got a lot of hands-on experience.”

Parekh looked bored. His eyes dropped again to the application form. Hannah spoke more quickly, injected a bit more enthusiasm into her voice.

“A large part of the appeal in transferring here to the University of Virginia was the prospect of working for the Innocence Project. I’ve been reading all about your work with Michael Dandridge, and the approach you’ve taken with the case is really inspiring.”

No reaction. Hannah hurried on. “I’ve been working on an accelerated timetable in Maine, so I’m ahead of where I need to be. I thought I might be helpful if some of your more experienced students are struggling with heavy class loads. I could pick up some of the slack.”

“What about your mother?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Don’t you have to spend time with your mother? Given her illness?”

“Mom’s doing much better now. She’s very independent.” Hannah’s throat tightened at the lie. “I’ll need to see her at weekends for a few hours. To catch up. Otherwise I’ll be free.”

Her words appeared to be having little impact. His eyes were on the papers in front of him.

“Hannah. All of the kids here are bright, they’re all hard workers, and they’re all motivated. I’m looking for something more. Your email made me think you might have it.”

Comments are closed.