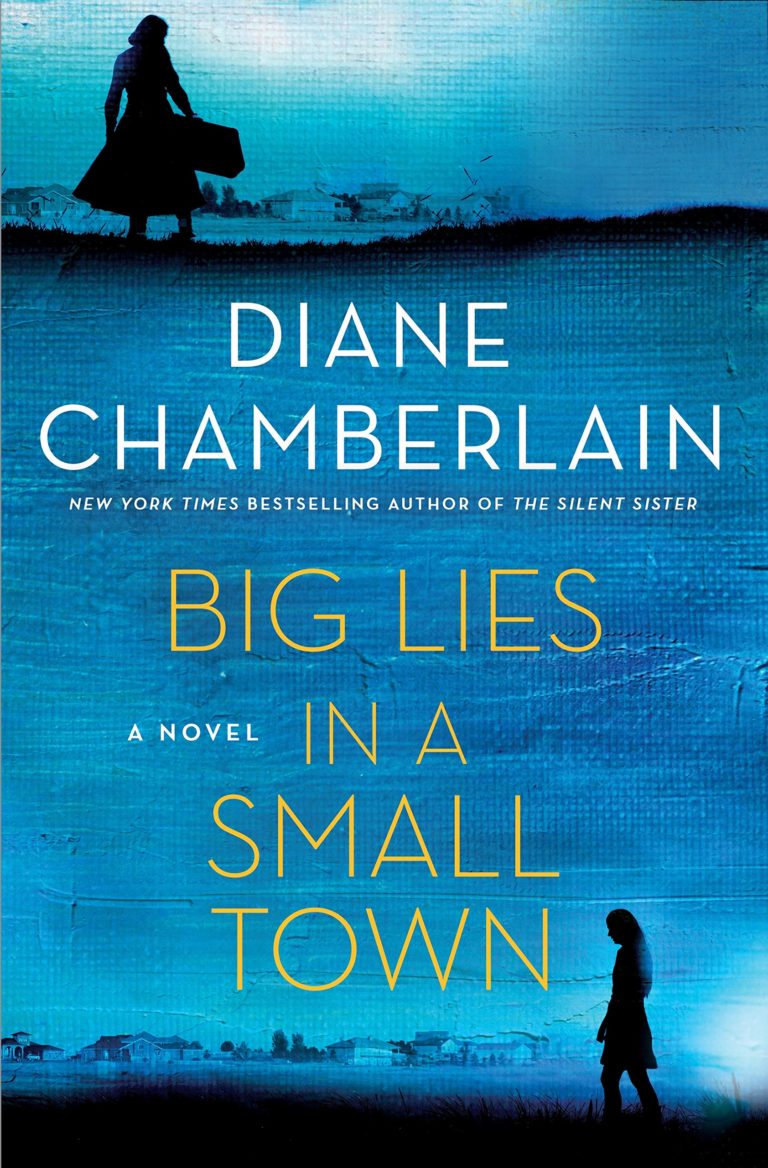

Synopsis:

Synopsis:

North Carolina, 2018: Morgan Christopher’s life derailed. After taking the fall for a crime she did not commit, she’s serving a three-year stint in the North Carolina Women’s Correctional Center. Her dream of a career in art is on hold until two mysterious visitors makes her an offer that is too good to turn down. She will be released immediately if she accepts the assignment: restore an old post office mural in a sleepy southern town. Morgan knows nothing about art restoration, but is desperate to get out of prison, so she accepts. What she finds under the layers of grime is a painting that tells a story of madness, violence, and a conspiracy of small town secrets.

North Carolina, 1940: Anna Dale, an artist from New Jersey, wins a national contest. She is selected to paint a mural that will grace the post office in Edenton, North Carolina. Anna is alone in the world and desperate for work, so she readily accepts the prized assignment. She doesn’t expect to find herself immersed in a small and small-minded town where prejudices run deep, people are hiding secrets, and the price of being different might end in murder.

What happened to Anna Dale? Are the clues to her fate hidden in the decrepit mural Morgan is charged with restoring? Can Morgan overcome her own demons to discover what exists beneath the layers of lies?

Review:

Bestselling author Diane Chamberlain earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work at San Diego State University. She initially worked at youth counseling agencies before embarking on a career in medical social work in San Diego and Washington, D.C. She also had a private psychotherapy practice, specializing in adolescents. But once her first novel, Private Relations, was published in 1989, she chose to focus on writing. She says that the stories she tells “are often filled with twists and surprises and –- I hope -– they also tug at the emotions.” Her settings vary from historical to contemporary, frequently include suspense, and she even ventured into science fiction with The Dream Daughter in which time travel was an intrinsic part of the tale. But all of her books have one thing in common. They “focus on relationships — between men and women, parents and children, sisters and brothers, friends and enemies.” Not surprisingly, considering her education and professional background, Chamberlain “can’t think of anything more fascinating than the way people struggle with life’s trials and tribulations, both together and alone.”

Since making North Carolina her “true home,” she has set several of her novels there, including Big Lies in a Small Town, her twenty-seventh novel. Chamberlain recalls that when she first visited “charming” Edenton, North Carolina, she knew she would set one of her stories there. When she learned about the Treasury Department’s “Special 48-State Mural Competition,” she felt that “Edenton’s history and industry lent itself perfectly to such a mural.” With help from the residents, she researched the history of Edenton and gained an understanding of what the little town of less than 5,000 residents was like during the Great Depression. Sixty percent of the population is African American and Chamberlain was delighted to be invited to attend the Racial Reconciliation Group to observe the way the townspeople strive for positive communication because she envisioned race relations being a dominant theme in Big Lies in a Small Town. Members of that group helped Chamberlain appreciate what life was like in 1940 for an African American teenager growing up in Edenton.

The story opens in June 2018 at the North Carolina Correctional Facility for Women in Raleigh, North Carolina, where Morgan, age twenty-two, has been incarcerated for a year. Via Morgan’s first-person narrative, readers learn that two unexpected visitors dramatically change the trajectory of Morgan’s life on that day. Raised by alcoholic parents who never really wanted her, Morgan also developed a drinking problem which culminated in a catastrophic vehicle accident and Morgan’s conviction for a crime she did not commit, but should have prevented. At the time, she was an art major, but irresponsible and misguided decisions derailed her education and the life she envisioned after graduation.

You have to make peace with the past or you can never move into the future.

Now Morgan is face to face with Lisa, the daughter of famed artist Jesse Jameson Williams, and her attorney. She learns that Jesse died five months earlier at the age of ninety-five. He spent the last twenty-five years of his life helping young artists “he thought had promise but were having a hard time with school or family or maybe just heading down the wrong path.” None of the women know how or why Morgan was on Jesse’s “Good Samaritan radar” — Morgan never met him — but he had decided she would be his “next project.” Now Morgan is being offered an early release from prison and $50,000 if she agrees to restore an old 1940s mural. Among the complications is the fact that Morgan has no expertise in art restoration, she must live in Edenton while performing the work, and the restoration must be completed in time for the opening of the gallery Jesse was building before his death. The restored mural must be hung in the foyer and the gallery must open on August 5th. The mural was supposed to be painted by Anna Dale and hung in the Edenton Post Office, but Anna never completed the painting. Jesse told Lisa that Anna “lost her mind while she was working on it,” but Lisa does not know how Jesse came into possession of the mural. Although Morgan has no idea how she will complete the work on the mural in time, she can’t pass up the “get out of jail free” card being offered to her.

In alternating chapters, Chamberlain employs a third-person narrative to tell the story of Anna Dale, who is notified in December 1939 that she has won the “Special 48-States Mural Competition” and awarded the opportunity to create a mural not for her hometown of Bordentown, New Jersey, but for the Edenton Post Office. Anna has never been to North Carolina and is not prepared for life in a small Southern town. “She’d never had any yearning to travel south of the Mason-Dixon line, and she was glad she’d only be here for a few days. The South seemed so backward to her” with its segregation laws. But the mural must be 12′ by 6′ and completed by June 3, 1940, in order for Anna to claim the prize money that she desperately needs. Initially, Anna plans to visit Edenton for three days in order to learn about the town and create her sketch of the mural which must be approved by the selection committee. She has just buried her mother and is reeling from her death. Soon it becomes clear that she will need to remain in Edenton so she agrees to rent a room from Myrtle Simms, a widow whose daughter, Pauline, has just married and moved out of her mother’s home. Ann brings few belongings to Edenton, but among them is a brown leather journal her mother gifted her shortly before she died, and strikes up a friendship with Pauline.

Chamberlain deftly advances the dual storylines as the two women face the challenges of creating and restoring the mural. Anna has a hard time adjusting to life in Edenton. She is pressured by the male leaders of the community about what scenes should be depicted in the mural. And there is Martin Drapple, the artist who was born and raised in Edenton. Of course, everyone in town knows him and most residents have one of his paintings hanging in their home. Everyone expected him to win the competition — especially Martin. His wife lets her resentment be known, but Martin offers to assist Anna with the mural after she adapts an abandoned warehouse outside of town into her makeshift studio. Does Martin have an ulterior motive? And Anna becomes the subject of gossip and speculation when a high school teacher asks her to let one of her most talented students join two other youngsters who are helping Anna with the mural. He’s failing most of his classes because all he wants to do is draw, and he needs more advanced tutelage than the teacher can give him. The only thing keeping him from dropping out of school is art class, but his future looks grim because his parents need him to remain at home and work alongside them on the family farm. Anna does not understand why the townspeople look down on her being alone with the young African American man in the warehouse as work on the mural proceeds. She is outraged by their blatant bigotry. The young man is indeed talented and Anna wants to guide him toward a future as an artist. He is none other than Jesse Williams, and he and Anna are destined to help each other in ways neither can foresee.

In 2018, Morgan’s work on the mural proceeds slowly as she resides with Lisa in the home Jesse left her. Her stress is exacerbated as she learns more about the strict provisions contained in his will and the penalties for noncompliance. The condition of the unfinished mural makes the restoration more challenging and time-consuming than Morgan anticipated, and the scenes it depicts are mysterious and troubling. Did Anna indeed suffer from mental illness while working on the mural? Morgan seeks answers from Lisa’s family members, but the one who might be able to answer Morgan’s many questions suffers from dementia. As Morgan works on the mural, she finds herself increasingly drawn to Oliver Jones, the gallery’s curator who, like her, is eager to unravel the mysteries of the mural and Anna, whose fate remains unknown. Morgan is hesitant to get involved with Oliver for a number of reasons, including the way her previous relationship ended. She is required to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and meet with her parole agent regularly, and is determined not to squander the chance she has been given to remain free. But she is haunted by memories of the night that ruined her life, as well as that of a young woman named Emily Maxwell. Can she forgive herself? Should she attempt to find Emily in an attempt to make amends?

Chamberlain explores the emotions Morgan and Anna experience during the months they spend in Edenton in a credible, compassionate manner. She gradually reveals details about Anna’s relationship with her mother and her fear that she might be more like her mother than she wants to be. She also believably depicts Anna’s difficulties adjusting to life in Edenton, particularly the misogyny and racism that shock and sadden her. Likewise, Morgan is a sympathetic, fully-developed character — a young woman who had a terrible childhood and must break free of the behavior patterns and beliefs she carried into adulthood that caused her to demonstrate extremely poor judgment. She is earnestly struggling to accept her mistakes and learn to forgive herself so that she can find peace. She develops a deep connection not just to the work she is performing on the mural, but to Anna, becoming extremely protective of her legacy and doggedly searching for clues to her fate. Both narratives move forward at a steady pace, ultimately merging as all of the big secrets and lies that have remained unknown for nearly eighty years are disclosed.

Once again, Chamberlain’s storytelling prowess makes Big Lies in a Small Town engrossing and emotionally resonant. Her characters are flawed, but endearing and empathetic. Chamberlain explores racial injustice, domestic violence, and mental illness and its destructive legacy. Betrayal, retribution, and murder factor into an intriguing mystery. True to her writing style, Chamberlain’s story is, at its core, focused on her characters’ relationships — friendship, loyalty, resilience, and, of course, forgiveness. And she succeeds at doing what she always does: Big Lies in a Small Town tugs at readers’ emotions and Chamberlain provides her memorable characters with a satisfying conclusion to their story.

Excerpt from Big Lies in a Small Town

Prologue

Edenton, North Carolina

March 23, 1940

The children knew it was finally spring, so although the air still held the nip of winter and the grass and weeds crunched beneath their feet, they ran through the field and woods, yipping with the anticipation of warmer weather. The two boys and their little sister headed for the creek, drawn to water, as they always were. The girl, only three and not as sure-footed as her brothers, tripped over something and landed face first in the cold water of the creek. Her big brother picked her up before she could start howling, cuddling her close against his thin jacket, a hand-me-down from one cousin or another. He looked down to see what she’d stumbled over and leaped back, dropping his sister to the earth. Grabbing his younger brother’s arm, he pointed. It was a man, lying there, his rumpled clothes sopping wet and his face as white and waxy as the candles their mama kept around the house for when the electric went out, which was every other day, it seemed.

The younger boy backed away. “He alive?” he whispered.

The little girl got to her feet and started moving toward the man, but her older brother grabbed her arm and held her back.

“Uh uh,” he said. “He dead as a doornail. And look”—he pointed—“his head all caved in.”

“Let’s git outta here!” the younger boy said, turning to run back the way they’d come, and his brother was quick to follow, holding their sister beneath his arm like a football. He knew they wouldn’t tell. Wouldn’t say nothing to their mama or no one. Because though they were young, one thing they’d already learned. Colored boy found with a dead white body? That didn’t never look good to nobody.

Chapter 1

Morgan

North Carolina Correctional Facility for Women

Raleigh, North Carolina

Friday June 8, 2018

This hallway always felt cold to me, no matter the time of year. Cinderblock walls, linoleum floor that squeaked beneath my prison issue shoes. You wouldn’t know what season it was from this hallway. Wouldn’t know it was June outside, that things were blooming and summer was on its way. It was on its way for those outside, anyway. I was facing my second summer inside these cinderblock walls and tried not to think about it.

“Who’s here?” I asked the guard walking by my side. I never had visitors. I’d given up expecting one of my parents to show up, and that was fine with me. My father came once after I’d been here a couple of weeks, but he was already wasted, although it wasn’t yet noon, and all he did was yell. Then he cried those sloppy drunk tears that always embarrassed me. My mother hadn’t come at all. My arrest held a mirror up to their flaws and now they were as finished with me as I was with them.

“Dunno who it is, Blondie,” the guard said. She was new and I didn’t know her name and couldn’t read the name tag hanging around her neck, but she’d obviously already learned my prison nickname. And while she might have been new to the NCCFW, I could tell she wasn’t new to prison work. She moved too easily down this hallway, and the burned out, bored, bitter look in her dark eyes gave her away.

I headed for the door to the visiting room, but the guard grabbed my arm.

“Uh uh,” she said. “Not that way. S’posed to take you in here today.” She turned me in the direction of the private visiting room, and I was instantly on guard. Why the private room? Couldn’t be good news.

I walked into the small room to find two women sitting at one side of a table. Both of them were somewhere between forty and fifty. No prison uniforms. They were dressed for business in suits, one navy the other tan. They looked up at me, unsmiling, their dark-skinned faces unreadable. I kept my gaze on them as I sat down on the other side of the table. Did they see the anxiety in my eyes? I’d learned to trust no one in this place.

“What’s this about?” I asked.

The woman in the tan suit sat forward, manicured hands folded neatly on the table. “My name is Lisa Williams,” she said. She had a pin on her lapel in the shape of a house, and she reminded me a little of Michelle Obama. Shoulder length hair. Perfectly shaped eyebrows. But she didn’t have Michelle Obama’s ready smile. This woman’s expression was somewhere between boredom and apprehension. “And this is Andrea Fuller. She’s an attorney.”

Andrea Fuller nodded at me. She was older than I’d thought. Fifty-something. Maybe even sixty. She wore her hair in a short, no-nonsense afro sprinkled with gray. Her lipstick was a deep red.

I shook my head. “I don’t understand,” I said looking from one woman to the other. “Why did you want to see me?”

“Andrea and I are here to offer you a way out of this place,” the woman named Lisa said. Her gaze darted to my lacy tattoo where it peeked out from beneath the short sleeve of my pale blue prison shirt. I’d designed the intricate tattoo myself–black lace crisscrossed with strings of tiny, three-dimensional pearls and chandelier jewelry. Lisa lifted her gaze to mine again. “As of next week, you’ve served your minimum sentence. One year, right?” she asked.

I half nodded, waiting. Yes, I’d served my one-year minimum, but the maximum was three years and from everything I’d been told, I wasn’t going anywhere for a long time.

“We . . . Andrea and I . . . have been working on getting you released,” Lisa said.

I stared at her blankly. “Why?” I asked. “You don’t even know me.” I knew there was some sort of program where law students tried to free prisoners who had been wrongly imprisoned, but I was the only person who seemed to think my imprisonment had been a mistake.

Andrea Fuller cleared her throat and spoke for the first time. “We’ve made the case that you’re uniquely qualified for some work Lisa would like you to do. Your release depends on your willingness to do that work and—”

“In a timely fashion,” Lisa interrupted.

“Yes, there’s a deadline for the completion of the work,” Andrea said. “And of course you’ll be under the supervision of a parole officer during that time, and you’ll also be paying restitution to the family of the girl you injured—the Maxwell family, and—”

“Wait.” I held up my hand. I was surprised to see that my fingers trembled and I dropped my hand to my lap. “Please slow down,” I said. “I’m not following you at all.” I was overwhelmed by the way the two women hopped around in their conversation. What work was I uniquely qualified to do? I’d worked in the laundry here at the prison, learning to fold sheets into perfect squares, and I’d washed dishes in hot chlorine-scented water until my eyes stung. They were the only unique qualifications I could think of.

Lisa lifted her own hands, palms forward, to stop the conversation. “It’s like this,” she said, her gaze steady on me. “Do you know who Jesse Jameson Williams was?”

Everyone knew who Jesse Jameson Williams was. The name instantly transported me to one of the rooms in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Four years ago now. No, five. I’d been seventeen on a high school trip. My classmates had been ready to leave the museum, but I’d wanted to stay, smitten by the contemporary art, so I hid in the restroom while my class headed out of the building. I didn’t know or care where they were going. I knew I’d get in trouble, but I would deal with that later. So I was alone when I saw my first Jesse Jameson Williams. The painting quite literally stole my breath, and I lowered myself to the sole bench in the gallery to study it. The Look, it was called. It was a tall painting, six feet at least, and quite narrow. A man and woman dressed in black evening clothes stood back to back against a glittery silver background, their bodies so close it was impossible to separate his black jacket from her black dress. They were both brown skinned, though the woman was several shades darker than the man. His eyes were downcast, as if the man was trying to look behind himself at the woman, but her eyes were wide open, looking out at the viewer—at me–as though she wasn’t quite sure she wanted to be in the painting at all. As though she might be saying, help me. When I could breathe again, I searched the walls for more of Jesse Jameson Williams’ work and found several pieces. Then, in the museum shop, I paged through a coffee table book of his paintings, wishing I could afford its seventy-five dollar price tag.

“He’s one of my favorite artists,” I answered Lisa.

“Ah.” For the first time, Lisa smiled, or nearly so, anyway. “That’s very good to hear, because he has a lot to do with my proposal.”

“I don’t understand,” I said again. “He’s dead, isn’t he?” I’d read about his death in the paper in the prison library. He’d been ninety-five and had certainly led a productive life, yet I’d still felt a wave of loss wash over me when I read the news.

“He died in January,” Lisa said, then added, “Jesse Williams was my father.”

“Really!” I sat up straighter.

“For the last twenty-five years of his life, he dedicated himself to helping young artists,” Lisa said.

I nodded. I’d read about his charitable work.

“Artists he thought had promise but were having a hard time with school or family or maybe just heading down the wrong path.”

Was she talking about me? Could Jesse Williams have seen my work someplace and thought there was something promising in it, something that my professors had missed? “I remember reading about some teenaged boy he helped a few years ago,” I said. “I don’t know where I—”

“It could have been any number of boys.” Lisa waved an impatient hand through the air. “He’d focus on one young man—or young woman–at a time. Make sure they had the money and support necessary to get the education they needed. He’d show their work or do whatever he saw fit to give them a boost.” She cocked her head. “He was a very generous man, but also a manipulative one,” she said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Shortly before he died, he became interested in you,” Lisa said. “You were going to be his next project.”

“Me?” I frowned. “I never even met him. And I’m white.” I lifted a strand of my straight, pale blond hair as if to prove my point. “Aren’t all the people he helped African American?”

Lisa shook her head. “Most, but definitely not all,” she said with a shrug. “And to be frank, I have no idea why he zeroed in on you. He often helped North Carolina artists, so that’s one reason—you’re from Cary, right?–but there are plenty of others he could have chosen. Why you were on his Good Samaritan radar is anyone’s guess.”

This made no sense. “Isn’t anything he had planned for me . . . or for anyone . . . didn’t his plans die with him?”

“I wish,” Lisa said. She smoothed a strand of her Michelle Obama hair behind her ear with a tired gesture. “My father’s still controlling things from the grave.” She glanced at Andrea with a shake of her head, while I waited, hands clutched together in my lap, not sure I liked this woman. “I lived with him,” Lisa continued. “I was his main caretaker and he was getting very feeble. He knew he was nearing the end and he met with his lawyer—” she nodded toward Andrea—“and updated his will. He was in the process of building a gallery in Edenton. An art gallery to feature his paintings and those of some other artists as well as some student work.”

“Oh,” I said, still puzzled. “Did he want to put one of my pieces in it?” Maybe that was it. Had he somehow heard about me and wanted to give my career—such as it was–a boost through exposure in his gallery? Ridiculous. How would he have heard about me? I couldn’t picture any of my professors at UNC singing my praises. And what on earth would I put in his gallery? My mind zigzagged through my paintings, all of them at my parents’ house . . . unless my parents had gotten rid of them, which wouldn’t have surprised me.

“Nothing that simple,” Lisa said. “He wanted you to restore an old 1940’s mural, and he stipulated that the gallery can’t be opened until the restored mural is in place in the foyer. And the date of the gallery opening is August fifth.”

This had to be a mistake. They had to be looking for someone else, and I felt my chance at freedom slipping away. Restore a mural? In two months? First, I had no experience in art conservation, and second, I’d worked on exactly one mural in my nearly three years in college and that had been a simple four by eight foot abstract I’d painted with another student my freshman year. “Are you sure he meant me?” I asked.

“Definitely.”

“Why does he . . . why would he think I’m ‘uniquely qualified’ to do this?” I asked, remembering the phrase. “How did he even know I exist?”

“Who knows?” Lisa said, obviously annoyed by her father’s eccentricities. “All I know is you’re now my problem.”

I bristled at her attitude, but kept my mouth shut. If the two of them could actually help me get out of here, I couldn’t afford to alienate them.

“I suppose he thought you were qualified by virtue of your art education,” Andrea said. “You were an art major, correct?”

I nodded. I’d been an art major, yes, but that had nothing to do with restoration. Restoration required an entirely different set of skills from the creation of art. Plus, I hadn’t been the most dedicated student that last year. I’d let myself get sucked in by Trey instead of my studies. He’d absorbed my time and energy. I’d been nauseatingly smitten, drawn in by his attention and the future we were planning together. He’d told me about his late grandmother’s engagement ring, hinting that it would soon be mine. I’d thought he was so wonderful. Pre-law. Sweet. Amazing to look at. I’d been a fool. But I knew better than to say anything about lack of qualifications to these two women when they were talking about getting me out of here.

“So . . . where’s this mural?” I asked.

“In Edenton. You’d have to live in Edenton,” Lisa said. “With me. My house—my father’s house, actually–is big. We won’t be tripping over each other.”

I could barely believe my ears. I’d not only get out of prison but I’d live in Jesse Jameson Williams’ house? I felt the unexpected threat of tears. Oh God, how I needed to get out of here! In the last miserable year, I’d been bruised, cut, and battered. I’d learned to fight back, yes, but that was not who I was. I was no brawler. My fellow inmates mocked me for my youth, my slender build, my platinum hair. I lived in a state of perpetual fear. Even in my cell, I felt unsafe. My cellmate was a woman who didn’t talk. Literally. I’d never heard a word from her mouth, but her expression carried disdain. I barely slept, one eye open, expecting to have my throat slit with a stolen knife sometime during the night.

And then there were the nightmares about Emily Maxwell, but I supposed I would bring them with me no matter where I went.

“You’ll work on the mural in the gallery, which is only partially built at this point,” Lisa interrupted my thoughts. “There’s plenty of room in the foyer. That’s where my father wanted it displayed.”

“It’s not painted on a wall?”

“No, it’s on canvas and it was never . . . hung, or whatever you call it.”

“Installed,” Andrea said.

“Right,” Lisa said. “It was never installed.”

“Who painted it?”

“A woman named Anna Dale,” Lisa said. “It’s one of those depression era murals. You know how, during the depression, the government hired artists to paint murals for public buildings?”

I nodded, though my memory of those WPA-type programs was sketchy at best.

“This mural was supposed to be for the Edenton Post Office. But Anna Dale went crazy or something—I can’t remember exactly what my father told me—she lost her mind while she was working on it, thus the finished product was never installed. My father’s owned it for decades and he wants—wanted–to hang it in the foyer of the gallery. And he said it has to be in place by the date the gallery opens.”

“August fifth,” Andrea said in case I hadn’t heard the date the first time. I most definitely had.

“That’s not even two months from now,” I said.

Lisa let out a long, anxious sounding breath. “Exactly,” she said. “Which is why you need to start on it immediately.”

“What kind of shape is it in?” I asked

.

Lisa shrugged. “I haven’t actually seen it. It’s been rolled up in a corner of my father’s studio closet all these years—it’s a massive thing–and I don’t know what condition it’s in. It must be salvageable, though, if he expected you to fix it.”

I tried to imagine what nearly seventy years would do to a huge canvas stuffed in a closet. What Lisa needed was a professional restoration company, not a novice artist. But what I needed was my freedom.

“Would I be paid?” I looked at Andrea. “If I have to pay restitution to –”

“My grandfather left fifty thousand for the project,” Lisa interrupted.

“For the whole gallery?”

“No.” Lisa said. “For you. For you to restore the mural. Fifty K, plus another several thousand for any supplies you need.”

Fifty thousand dollars? Incredible. Even if I’d gotten my degree, I doubted I could have found a job that would pay me that much in a year’s time, much less for two months’ work. Two months’ work I had no idea how to do. I tried to keep my self doubt from showing on my face. Uniquely qualified? Not hardly.

“This is your get out of jail free card, Morgan.” Andrea leaned forward, her red lips forming the words slowly and clearly. “If you hold up your end of the bargain—finishing your work–quality work–on the mural by the fifth of August—you’ll be out on parole and will never have to set foot in this place again. If I were you, I’d start reading up on restoration.”

I looked toward the doorway of the small room. I imagined walking through it and down the hallway to the front entrance and freedom. I imagined twirling in circles outside, my arms stretched wide to take in the fresh air. I didn’t think I’d ever be completely free of this place, though. I’d always carry my prison with me. I felt that imaginary prison closing around me even as I sat there, even as I imagined walking out the front door.

Still, I would rather an imaginary prison than this hideous real one.

“I’ll do it,” I said finally, sitting back.

How I would do it, I had no idea.

Chapter 2

Anna

December 4, 1939

Edenton, North Carolina

From the United States Treasury Department, Section of Fine Arts

Special 48-States Mural Competition

Dear Miss Anna Dale,

The Section of Fine Arts is pleased to inform you that you are one of the winning artists in the 48-States Mural Competition. Your sketch for the proposed mural to adorn the Bordentown, New Jersey Post Office received many positive comments from the judges. Unfortunately, a different artist has been awarded the Bordentown post office, but the judges were sufficiently impressed with your work that they would like you to undertake the creation of the mural for the post office in Edenton, North Carolina. This will require that you send us a sketch for the Edenton assignment as soon as possible. Once you receive the Section’s approval on the sketch, you can begin the actual work on the (full size) cartoon and finally, the mural itself. The size of the Edenton mural will be 12’ by 6’. The project is to be completed by June 3, 1940.

It is suggested that artists become familiar with the geographic area of the post office for which they’re painting and make a special effort to select appropriate subject matter. The following subjects are suggested: Local History, Local Industries, Local Flora and Fauna, and Local Pursuits. Since the location of Edenton, North Carolina was not your first choice and you are therefore most likely not familiar with the town, it is strongly suggested you make a visit there as soon as possible.

The payment for the mural will be $720, one third payable on the approval of your sketch, one third payable on the approval of your cartoon, one third payable upon installation of the final mural. Out of this amount, you will pay for your supplies, models if needed, any travel, and all costs related to the installation of the mural.

Sincerely, Edward Rowan, Art Administrator, Section of Fine Arts

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anna arrived in Edenton for her planned three-day visit late on the afternoon of December fourth. She could have taken the overnight train, but at the last minute she decided to drive. The ’32 navy blue Ford V8 still held her mother’s scent—the spicy patchouli fragrance of the Tabu perfume she’d loved–and Anna needed that comfort as she set out on this new, very adult venture. Her first paying job. Her first time away from home. Her first everything, really.

The car skidded on a patch of ice as she turned onto Broad Street in the fading sunlight, and for a moment she was certain her introduction to the town would consist of slamming into a row of parked cars, but she managed to get the Ford under control. As soon as she did, she found herself behind a cart drawn by a horse, or perhaps a mule. She couldn’t get a good look at the animal and wasn’t sure she’d know one from the other anyway. She didn’t see many of either in her hometown of Plainfield, New Jersey.

She slowed down, thinking she should get a good look at the little town that would be the subject of her mural. When she’d viewed Edenton in the atlas, it had been a watery looking place, nothing more than a speck surrounded by a bay and a river. Even on the map, it had looked strangely foreign to her, and she’d closed the atlas with a worried sigh.

She hadn’t expected to win the competition, and the timing could not have been worse. She’d just buried her mother. Her best friend. The one person in the world whose love and nurturing Anna could always count on. But she couldn’t turn down work, not with jobs so impossible to find. Not when her mother was no longer around to bring in the sewing money that had paid for their food and expenses. No, she needed to be grateful for this opportunity, even if it meant she had to travel more than four hundred miles to ‘become familiar with the geographic area’ she was to immortalize in the mural.

She’d never had any yearning to travel south of the Mason-Dixon line, and she was glad she’d only be here for a few days. The South seemed so backwards to her. Segregated schools and ridiculous laws about keeping colored and white apart on buses and at water fountains and in restrooms. She’d had a few colored classmates at Plainfield High School and she’d counted a couple of the girls as friends. They’d been on the basketball team and in glee club together.

“You’re looking at Plainfield through rose-colored glasses,” her mother would have said. Even in Plainfield, those colored girls Anna thought of as her friends couldn’t go into certain shops or restaurants with her, and one of them told her she had to sit in the balcony at the Paramount Theater. The roller rink had a ‘colored night’ set aside for them each week and they—as well as Anna’s Jewish friends–were unwelcome at the Country Club. But still, everyone knew it was worse in the south. They actually lynched Negroes in the south.

She’d considered simply doing her research for the mural in the Plainfield Public Library, knowing the drive to Edenton would take her two full days, but she’d read and reread the letter from the Section of Fine Arts that advised her to visit the little town. Her mother would have told her to do the job properly. Anna imagined her saying “be grateful for the work, sweetheart, and embrace the challenge.” Her friends who recently graduated with her from the Van Emburgh School of Art in Plainfield were still hunting for jobs that simply didn’t exist, with the economy the way it was. Many of them had also tried to win the Section of Fine Arts competition and Anna knew how lucky she was to have been given the honor. She would do everything she could to make the Section glad they put their trust in her.

A few days before she died, her mother had given Anna a journal. The book of blank pages was bound in velvety soft brown leather, the cover fastened together with a simple gold lock and key. So beautiful. Her mother had known then that it would be the last gift she would ever give her daughter, but Anna hadn’t known. She’d thought it was a graduation present, not a goodbye gift. It angered her when she realized the truth, and she didn’t want to feel that emotion toward her mother. In a fit of rage, she’d tossed the journal in the kitchen trashcan, but she dug it out again, cleaned it off, and now it was packed it in her suitcase. She wouldn’t throw away anything connected to her mother again. She needed to hold on to it all.

She also had her mother’s camera with her. Anna had choked up as she sat at the kitchen table winding a new roll of film into the Kodak Retina. She pictured her mother’s hands doing the same task over the years . . . although when Anna thought about it, she realized many months had passed since her mother had picked up the camera. Photography had been her passion. It brought in no money, but had given her great pleasure during her “lively spells.” The doctor called them “manic episodes” but Anna preferred her own term. The lively spells were always a relief to Anna when they followed the days—sometimes the weeks–when her mother could barely get out of bed. The lively spells came without warning, often with behavior that was impossible to predict. She’d awaken Anna early to inform her she was skipping school, and they’d take the bus to New York where they’d race through museum after museum or roller skate through Central Park. One time, when Anna was about twelve, they slipped in the rear door of Carnegie Hall, found a couple of empty box seats, and watched an orchestra perform. It wasn’t the music Anna remembered from that day. It was the sheer joy of sitting next to her mother, leaning her head against her shoulder, feeling her wired energy. Knowing that, for as long as the lively spell lasted, their days would be joy-filled.

When the good spells came during the spring, as they often did, one of her mother’s favorite activities was to walk at a brisk clip through Plainfield’s neighborhoods, carrying her camera, snapping pictures of people’s gardens. She adored flowers and she’d walk up the driveways of strangers to reach window boxes overflowing with geraniums, even ducking behind the houses to capture backyard gardens filled with roses and hydrangeas and peach-colored day lilies. As far as Anna knew, no one every badgered her mother about the intrusion. Maybe people had thought of her as a bit of a kook. Or perhaps they’d felt sorry for her, a woman widowed young with a daughter to raise. Or maybe they knew the truth–Mrs. Dale was not a well woman—and they kindly let her be.

Anna fended for herself when her mother’s spirits were low. She’d cook for both of them, although her mother ate almost nothing during those times. She’d clean the house and do the laundry. She did it all with patience, with love, waiting out the melancholia. There was one terrible time when Aunt Alice dragged Anna’s mother to a psychiatrist who insisted she be hospitalized. For two long months, Anna, then fourteen, lived with her aunt and uncle, angry at them both for putting her mother in that terrible place. When her mother was finally released, there were gaps in her memory, precious moments the hospital seemed to have stolen from her, and Anna vowed she would never let anyone lock her away again. She tried to keep her mother’s low moods a secret from her aunt after that, making light of them, riding them out. Perhaps, though, she’d made a mistake this last time. Perhaps this last time, her mother had needed more help than Anna had been able to give her. She tried not to think about that. She’d simply been waiting for the lively spell to return. She’d lived with her mother long enough to know that, in time, the smiling, happy mother she adored would come back, full of crazy ideas that would leave both of them giggling with wonder.

“Never be afraid to try something new, Anna,” her mother would say.

That’s what Anna was doing now, wasn’t it? Driving for two whole days through unfamiliar territory, landing in a tiny town where she didn’t know a soul? From somewhere in the heavens, her mother was applauding.

The letter from the Section of Fine Arts had arrived with a list of the winners of all forty-eight states. Anna had felt embarrassed and intimidated when she looked at that list. The contest had been anonymous, which she assumed was the only reason she’d been able to win. Still, many of the other winners were famous artists. There was So and So, from New York City, president of the League of Artists, studied in Europe, experienced muralist, had one man exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles, and on and on. Winner after winner had accolade after accolade. And then there was Anna: Anna Dale. Plainfield, New Jersey. Born 1918. Graduate of Van Emburgh School of Art. And that was it. She thought the panel of judges must have been stunned into silence when they opened her envelope to discover the inexperienced girl they’d selected. She had to keep reminding herself that they’d legitimately picked her, fair and square, and she remembered what Mrs. Van Emburgh had whispered in her ear when she handed Anna her graduation certificate: “You are a standout, Anna,” she’d said. “You have a future in the art world.” Her words still sent a shiver up Anna’s spine. She’d told no one about them, not wanting to appear conceited, but she clung tight to the compliment now that she’d won the competition. Now that she was, so completely, on her own.

She had to come up with a whole new idea for a sketch very quickly, and the thought overwhelmed her. The concept for her Bordentown sketch had come to her easily. Clara Barton had founded the first free public school in Bordentown, so Anna had painted her ringing the school bell outside a little red brick schoolhouse with lines of children walking and skipping to the school. She was proud of the way she captured the swish of the girls’ skirts and the energy of the boys. Too bad she wouldn’t be able to paint that mural now. The memory of her eager, happy production of that sketch, before everything changed, seemed to be from another lifetime.

She did have an idea for the Edenton mural, though. In the Plainfield library, the librarian pointed her toward the American Guide Series’ book on North Carolina. In it, she read about the ‘Edenton Tea Party’, an eighteenth century women’s movement in which fifty-one women signed a petition to boycott all English products. She thought that might make an intriguing mural and wouldn’t be too challenging to paint. The idea seemed so simple to her at first that she thought she might not even have to travel to Edenton to do her research, but then she realized she actually wanted this trip. She needed to get away for a few days. She needed an escape from the sadness in the little house where she expected to see her mother every time she walked into another room.

King Street. She spotted the sign and turned left to see a big brick block of a building. The Hotel Joseph Hewes. It would be her home while she was in this town she knew as well as she knew Jupiter or Saturn. She drove into the parking lot, heart pounding, hands sticky on the steering wheel, wondering what the next few days would hold.

Comments are closed.