Synopsis:

Synopsis:

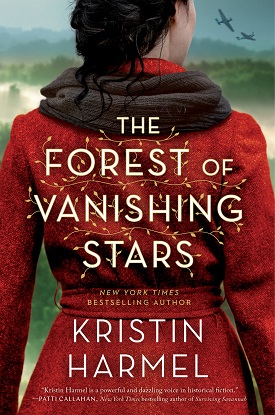

After being stolen from her wealthy German parents and raised in the unforgiving wilderness of eastern Europe, a young woman finds herself alone in 1942 after her kidnapper dies. Her solitary existence is interrupted, however, when she happens upon a group of Jews fleeing the Nazis. Stunned to learn what’s happening in the outside world, she vows to teach the group all she can about surviving in the forest. In turn, they teach her some surprising lessons about opening her heart after years of isolation.

But when she is betrayed and escapes into a German-occupied village, her past and present come together in a shocking collision that could change everything.

The Forest of Vanishing Stars was inspired by incredible true stories of survival against staggering, seemingly insurmountable odds.

Review:

Kristin Harmel is the bestselling author of fourteen prior novels, including The Book of Lost Names and The Winemaker’s Wife. She began her writing career at the age of sixteen as a sportswriter in Tampa Bay, Florida. She covered baseball and hockey before segueing into reporting on health and lifestyles. She earned a degree in journalism from the University of Florida and served for more than a decade as a reporter for People magazine, covering a wide variety of topics. Her favorite articles were the “Heroes Among Us” features spotlighting ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Her writing was also published in numerous other magazines and she contributed to The Daily Buzz, a morning television show. After stints residing in Paris and Los Angeles, she now lives in Orlando, Florida, and is a co-founder and co-host of the weekly web show and podcast Friends & Fiction.

Harmel can’t say exactly what led her to pen the The Forest of Vanishing Stars, although she had heard vaguely about Jewish refugees who survived World War II by hiding in the forests of Eastern Europe. She conducted extensive research and had begun writing the book when her brother sent her a link to a family tree revealing that some of her family members were from an area not far from where she sets the story. “It touched something so deep in me,” she relates. Her great-great-grandparents arrived in America in 1888, and she learned that her great-great-grandmother, Rose, returned to Poland for a visit in 1933 for a visit, six years before the Nazis invaded Poland. Harmel pondered what Rose must have felt knowing that loved ones she had just visited a few years earlier “were probably meeting an unspeakable fate.” She adds, “I don’t know if I’m a big believer that stories live in our blood . . . but what other explanation is there than there was something a little bit beyond my grasp taking place that led me here at this time to tell this story?”

The Forest of Vanishing Stars is an engrossing fictional account of a young woman who helps Jews live in the forest and escape apprehension. Although none of her characters are based on real people, one resource was the story of Aron Bielski, a member of the only Jewish family in the little village of Stankiewicze, Poland, where they owned and operated a mill. The youngest of twelve children, the Germans had been searching for his older brothers for months. In fact, they captured Aron and tried to coerce him to reveal his brothers’ whereabouts by ordering him to dig his own grave and lie in it with a pistol pointed at him. So when he spotted a police vehicle on December 5, 1941, he hid in the barn. His parents were arrested and killed, along with four thousand other Jews, including two of his sisters-in-law and his infant niece. He fled into the forest where he was reunited with two of his brothers, and they joined a group of other Jews that eventually numbered twelve hundred. They became a self-sufficient community that existed hidden away until the war ended and it was safe to emerge because they “found trust, life, and hope in the darkness.” But survivor’s guilt became Aron’s constant companion. He told Harmel, “Sorrow teaches a person how to live, how to survive, what to do next.”

In Harmel’s story, an old mystic woman, Jerusza, who had “always known things other people didn’t,” knows that a child born to wealthy and influential German parents must not remain with and be raised by them. Her destiny lies elsewhere. So she watches and waits, and when the little girl, Inge Jüttner, is two years old, she kidnaps her. The child looks up at her and says “It is you” in Yiddish, a language she has not been taught. As they are escaping, Jerusza hears “a voice from the sky, sharp and clear. One day, the voice said, if she is not careful, her past will return — and it will cost her everything. The only safe place is the forest.” So Jerusza takes her to the Nalibocka forest, changes her name to Yona and, although she never wanted a child of her own, raises her.

As the years pass, Jerusza teaches Yons how to exist concealed from society and dependent only on what the earth provides . . . along with the things Jerusza steals when they stealthily sneak into villages. And how to take another’s life should it become necessary, telling her, “There are hundreds of ways to take a life. And you must know them all.” As Yona grows and asks all sorts of questions, Jerusza teaches her languages, science, world religions, and how to steal books. In fact, by the team Yona is fourteen years old, the “bright, sensitive, intuitive” girl’s education rivals that of any university graduate. But most importantly, Yona masters “the mysteries of the forest, all the ways to survive.” Jerusza also shows her “the perils of the outside world, and reminds her that no one could be trusted.” Once, Yona defies Jerusza’s rules, delighted when she encounters a boy in the forest. But, of course, Jerusza knows about the young man Yona believes wants to be her friend, and insists that they gather their things and move to another area of the woods. They move about once every month, leaving no trace of their existence behind.

But by the time Yona is twenty years old, the world beyond the forest has changed. They hear airplanes, explosions, and gunshots, but Jerusza refuses to answer Yona’s queries about what is happening, saying only that “God is angry. We are being tested,” and reminding her that she will always be protected by the forest. There are more people in the forest — “Bad men. The horror has just begun,” Jaresza cautions — and they keep moving east. By the summer of 1941, Jerusza tells Yona that the Germans are bombing Poland and they must steer clear of Russian deserters.” But Yona is only confused by Jerusza’s statement.

At the age of 102, Jerusza dies in 1942, leaving twenty-two-year-old Yona on her own for the first time in her life. Yona had fleeting dreams about her first two years of life, but as she is dying, Jerusza confesses that she didn’t save Yona after she was abandoned by heartless parents. “I stole you. I had not choice, you see,” she admits.

In the times of greatest darkness, the light always shines through, because there are people who stand up to do brave, decent things,” says one of the men Yona meets in the forest. “In moments like this, it doesn’t matter what you were born to be. It matters what you choose to become.”

After Jerusza dies, Yona wanders the forest alone until she discovers and helps a little Jewish girl who tells her, “I was running from the . . . the people who want to kill us. Because I am Jewish. they are trying to kill us all.” Yona is stunned, unable to comprehend that anyone would capable of such a heinous act. Not long after, following a shattering tragedy, Yona finds a man attempting to catch a fish with his bare hands, and soon another man appears. Yona debates whether to help them. But the compulsion to intercede is irresistible, and she is convinced it is the right thing to do because it is part of a greater plan she does not yet understand. And the focus of Harmel’s story transitions from Jerusza’s efforts to prepare Yona for what she knows the young woman will have to face to Yona’s coming-of-age and fulfillment of her destiny.

Yona has no idea how to interact with other people, live in society, or love anyone other than in the limited ways she cared for Jerusza. But she becomes a teacher and leader when she realizes that the two men are part of a larger group. She joins them and shows them how to evade the Nazis in order to survive, especially during the rapidly approaching harsh winter. She learns difficult lessons about love, and a stinging betrayal compels her to return to the world from which she was ripped as a toddler. But there are more harsh lessons to be learned there about war, sacrifice, and the atrocities of which people are capable when committed to a cause.

Through Yona, Harmel explores the question of how much power individuals have to change their own destinies. In her skillful depiction of Yona’s struggle, the young woman comes face to face with her past and the life she could have led if Jerusza had not kidnapped her. She confronts the extent, if any, to which she is culpable, because she was born to German parents, for the suffering and loss of so many. One character pointedly challenges Yona, “You think you can escape who you were born to? None of us can. Can’t you see that?” Yet another character assures her, “We all come into this world with our fate unwritten. Your identity isn’t determined by your birth. All that matters is what we make ourselves into, what we choose to do with our lives.” Yona must make the most important decision of her life: which philosophy will she embrace? Who will she become? And as she does, with everything at stake, Harmel deftly ramps up the dramatic tension to a harrowing climax.

In Yona, Harmel has crafted an endearing and empathetic character. The elements of magical realism she injects into the tale are extremely effective at emphasizing the book’s themes. Her prose is descriptive and vibrant, with just the right level of detail to keep readers engaged during the first part of the book as Harmel sets the stage for the wrenching, heartbreaking events that occur later in the story when Yona matures and discovers her true purpose in life. Along the way, Jerusza’s beliefs and predictions serve as reminders that immortal forces have always been and continue to be at work in Yona’s life. But that Yona will, ultimately, be the person she chooses to be.

Harmel says she is drawn back to writing historical fiction set in the World War II-era because there are so many fascinating stories to tell and those stories remain relevant eight decades later. It was a dark period in history, but many of the tales serve as reminders that light always prevails. Indeed, light plays an important role in The Forest of Vanishing Stars in which the forest itself serves as a fundamental character. Yona moves in and out of the light the forest provides, hiding herself and others in darkness, emerging back into the light cautiously when it is safe to do so. As she is growing up, Yona and Jerusza sleep in the forest under a bright canopy of the same stars that the refugees wish upon as they wait for the war to end. Those stars sometimes remain unseen for months on end as winter descends, making it easier for Yona and the refugees to conceal themselves from their would-be captors. “You can hardly see them above the trees. They disappear deep in the forest, don’t they?” one of the refugees observes. “By the grace of God, may we all be vanishing stars.” As the refugees cautiously light the candles in the menorah Yona makes for them, they experience “light in the darkness. The hope of a miracle.”

Just as the refugees who survive declare that they must live in order to honor their dead, Harmel is committed to honoring those who were impacted by World War II with her fictional tales. With The Forest of Vanishing Stars she has excelled at honoring those who escaped to the forest in order to survive, as well as those who rendered them aid. It is an exquisite, compassionately crafted, and memorable story. A must-read for all fans of World War II-era historical fiction.

Excerpt from The Forest of Vanishing Stars

Chapter One

1922

The old woman watched from the shadows outside Behaimstrasse 72, waiting for the lights inside to blink out. The apartment’s balcony dripped with crimson roses, and ivy climbed the iron rails, but the young couple who lived there—the power-hungry Siegfried Jüttner and his aloof wife, Alwine — weren’t the ones who tended the plants. That was left to their maid, for the nurturing of life was something only those with some goodness could do.

The old woman had been watching the Jüttners for nearly two years now, and she knew things about them, things that were important to the task she was about to undertake.

She knew, for example, that Herr Jüttner had been one of the first men in Berlin to join the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, a new political movement that was slowly gaining a foothold in the war-shattered country. She knew he’d been inspired to do so while on holiday in Munich nearly three years earlier, after seeing an angry young man named Adolf Hitler give a rousing speech in the Hofbräukeller. She knew that after hearing that speech, Herr Jüttner had walked twenty minutes back to the elegant Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten, had awoken his sleeping young wife, and had lain with her, though at first she had objected, for she had been dreaming of a young man she had once loved, a man who had died in the Great War.

The old woman knew, too, that the baby conceived on that autumn-scented Bavarian night, a girl the Jüttners had named Inge, had a birthmark in the shape of a dove on the inside of her left wrist.

She also knew that the girl’s second birthday was the following day, the sixth of July, 1922. And she knew, as surely as she knew that the bell-shaped buds of lily of the valley and the twilight petals of aconite could kill a man, that the girl must not be allowed to remain with the Jüttners.

That was why she had come.

The old woman, who was called Jerusza, had always known things other people didn’t. For example, she had known it the moment Frédéric Chopin had died in 1849, for she had awoken from a deep slumber, the notes of his “Revolutionary Étude” marching through her head in an aggrieved parade. She had felt the earth tremble upon the births of Marie Curie in 1867 and Albert Einstein in 1879. And on a sweltering late June day in 1914, two months after she had turned seventy-four, she had felt it deep in her jugular vein, weeks before the news reached her, that the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne had been felled by an assassin’s bullet, cracking the fragile balance of the world. She had known then that war was brewing, just as she knew it now. She could see it in the dark clouds that hulked on the horizon.

Jerusza’s mother, who had killed herself with a brew of poisons in 1860, used to tell her that the knowing of impossible things was a gift from God, passed down through maternal blood of only the most fortunate Jewish women. Jerusza, the last of a bloodline that had stretched for centuries, was certain at times that it was a curse instead, but whatever it was, it had been her burden all her life to follow the voices that echoed through the forests. The leaves whispered in the trees; the flowers told tales as old as time; the rivers rushed with news of places far away. If one listened closely enough, nature always spilled her secrets, which were, of course, the secrets of God. And now, it was God who had brought Jerusza here, to a fog-cloaked Berlin street corner, where she would be responsible for changing the fate of a child, and perhaps a piece of the world, too.

Jerusza had been alive for eighty-two years, nearly twice as long as the typical German lived. When people looked at her — if they bothered to look at all — they were visibly startled by her wizened features, her hands gnarled by decades of hard living. Most of the time, though, strangers simply ignored her, just as Siegfried and Alwine Jüttner had done each of the hundreds of times they had passed her on the street. Her age made her particularly invisible to those who cared most about appearance and power; they assumed she was useless to them, a waste of time, a waste of space. After all, surely a woman as old as she would be dead soon. But Jerusza, who had spent her whole life sustained by the plants and herbs in the darkest spots of the deepest forests, knew that she would live nearly twenty years more, to the age of 102, and that she would die on a spring Tuesday just after the last thaw of 1942.

The Jüttners’ maid, the timid daughter of a dead sailor, had gone home two hours before, and it was a few minutes past ten o’clock when the Jüttners finally turned off their lights. Jerusza exhaled. Darkness was her shield; it always had been. She squinted at the closed windows and could just make out the shape of the little girl’s infant bed in the room to the right, beyond pale custard curtains. She knew exactly where it was, had been into the room many times when the family wasn’t there. She had run her fingers along the pine rails, had felt the power splintering from the curves. Wood had memory, of course, and the first time Jerusza had touched the bed where the baby slept, she had been nearly overcome by a warm, white wash of light.

It was the same light that had brought her here from the forest two years earlier. She had first seen it in June 1920, shining above the treetops like a personal aurora borealis, beckoning her north. She hated the city, abhorred being in a place built by man rather than God, but she knew she had no choice. Her feet had carried her straight to Behaimstrasse 72, to bear witness as the raven-haired Frau Jüttner nursed the baby for the first time. Jerusza had seen the baby glowing, even then, a light in the darkness no one knew was coming.

She didn’t want a child; she never had. Perhaps that was why it had taken her so long to act. But nature makes no mistakes, and now, as the sky filled with a cloud of silent blackbirds over the twinkling city, she knew the time had come.

It was easy to climb up the ladder of the modern building’s fire escape, easier still to push open the Jüttners’ unlatched window and slip quietly inside. The child was awake, silently watching, her extraordinary eyes—one twilight blue and one forest green—glimmering in the darkness. Her hair was black as night, her lips the startling red of corn poppies.

“Ikh bin gekimen dir tzu nemen,” Jerusza whispered in Yiddish, a language the girl would not yet know. I have come for you. She was startled to realize that her heart was racing.

She didn’t expect a reply, but the child’s lips parted, and she reached out her left hand, palm upturned, the dove-shaped birthmark shimmering in the darkness. She said something soft, something that a lesser person would have dismissed as the meaningless babble of a little girl, but to Jerusza, it was unmistakable. “Dus zent ir,” said the girl in Yiddish. It is you.

“Yo, dus bin ikh,” Jerusza agreed. And with that, she picked up the baby, who didn’t cry out, and, tucking her close against the brittle curves of her body, climbed out the window and shimmied down the iron rail, her feet hitting the sidewalk without a sound.

From the folds of Jerusza’s cloak, the baby watched soundlessly, her mismatched ocean eyes round, as Berlin vanished behind them and the forest to the north swallowed them whole.

Chapter Two

1928

The girl from Berlin was eight years old when Jerusza first taught her how to kill a man.

Of course Jerusza had discarded the child’s given name as soon as they’d reached the crisp edge of the woods six years earlier. Inge meant “the daughter of a heroic father,” and that was a lie. The child had no parent now but the forest itself.

Furthermore, Jerusza had known, from the moment she first saw the light over Berlin, that the child was to be called Yona, which meant “dove” in Hebrew. She had known it even before she saw the girl’s birthmark, which hadn’t faded with time but had grown stronger, darker, a sign that this child was special, that she was fated for something great.

The right name was vital, and the old woman couldn’t call Yona anything other than what she was. She expected the same in return, of course, a respect for one’s true identity. Jerusza meant “owned inheritance”—a reference to the magic she had received from her own bloodline, and a tribute to being owned by the forest itself—and it was the only thing she allowed Yona to call her. “Mother” meant something different, something that Jerusza never would be, never wanted to be.

“There are hundreds of ways to take a life,” Jerusza told the girl on a fading July afternoon soon after the child’s eighth birthday. “And you must know them all.”

Yona looked up from whittling a tiny wren from a piece of wood. She had taken to carving creatures for company, which Jerusza did not understand, for she herself valued solitude above all else, but it seemed a harmless enough pursuit. Yona’s hair, the color of the deepest starless night, tumbled down her back, rolling over birdlike shoulders. Her eyes—endless and unsettling— were misty with confusion. The sun was low in the sky, and her shadow stretched behind her all the way to the edge of the clearing, as if trying to escape into the trees. “But you’ve always told me that life is precious, that it is God’s gift to man, that it must be protected,” the girl said.

“Yes. But the most important life to protect is your own.” Jerusza f lattened her palm and placed the edge of her hand across her own windpipe. “If someone comes for you, a hard blow here, if delivered correctly, can be fatal.”

Yona blinked a few times, her long lashes dusting her cheeks, which were preternaturally pale, always pale, though the sun beat down on them relentlessly. As she set the wooden wren on the ground beside her, her hands shook. “But who would come for me?”

Jerusza stared at the child with disgust. Her head was in the clouds, despite Jerusza’s teachings. “You foolish child!” she snapped. The girl shrank away from her. It was good that the girl was afraid; terrible things were coming. “Your question is the wrong one, as usual. There will come a day when you’ll be glad I have taught you what I know.”

It wasn’t an answer, but the girl wouldn’t cross her. Jerusza was strong as a mountain chamois, clever as a hooded crow, vindictive as a magpie. She had been on the earth for nearly nine decades now, and she knew the girl was frightened by her age and her wisdom. Jerusza liked it that way; the child should be clear that Jerusza was not a mother. She was a teacher, nothing more.

“But, Jerusza, I don’t know if I could take a life,” Yona said at last, her voice small. “How would I live with myself?”

Jerusza snorted. It was hard to believe the girl could still be so naive. “I’ve killed four men and a woman, child. And I live with myself just fine.”

Yona’s eyes widened, but she didn’t speak again until the light had faded from the sky and the day’s lessons had ended. “Who did you kill, Jerusza?” she whispered in the darkness as they lay on their backs on the forest f loor beneath a roof of spruce bark they’d built themselves just the week before. They moved every month or two, building a new hut from the gifts the forest gave them, always leaving a crack in their hastily hewn bark ceilings to see the stars when there was no threat of rain. Tonight, the heavens were clear, and Jerusza could see the Little Dipper, the Big Dipper, and Draco, the dragon, crawling across the sky. Life changed all the time, but the stars were ever constant.

“A farmer, two soldiers, a blacksmith, and the woman who murdered my father,” Jerusza replied without looking at Yona. “All would have killed me themselves if I’d given them a chance. You must never give someone that opportunity, Yona. Forget that lesson, and you will die. Now get some rest.”

By the next full moon, Yona knew that a kick just to the right of the base of the spine could puncture a kidney. A horizontal blow with the edge of the hand to the bridge of the nose could crush the facial bones deep into the skull, causing a brain hemorrhage. A hard toe kick to the temple, once a man was down, could swiftly end a life. A quick headlock behind a seated man, combined with a sharp backward jerk, could snap a neck. A knife sliced upward, from wrist to inner elbow along the radial artery, could drain a man of his blood in minutes.

But the universe was about balance, and so for each method of death, Yona taught the girl a way to dispense healing, too. Bilberries could restore circulation to a failing heart or resuscitate a dying kidney. Catswort, when ground into a paste, could stop bleeding. Burdock root could remove poison from the bloodstream. Crushed elderberries could bring down a deadly fever.

Life and death. Death and life. Two things that mattered little, for in the end, souls outlived the body and became one with an infinite God. But Yona didn’t understand that, not yet. She didn’t yet know that she had been born for the sake of repairing the world, for the sake of tikkun olam, and that each mitzvah she was called to perform would lift up divine sparks of light.

If only the forest alone could sustain them, but as the girl grew, she needed clothing, milk to strengthen her bones, shoes so her feet weren’t shredded by the forest floor in the summer or frozen to ice in the winter. When Yona was young, Jerusza sometimes left her alone in the woods for a day and a night, scaring her into staying put with tales of werewolves that ate little girls, while she ventured alone into nearby towns to take the things they needed. But as the girl began to ask more questions, there was no choice but to begin taking her along, to show her the perils of the outside world, to remind her that no one could be trusted.

It was a cold winter’s night in 1931, snow drifting down from a black sky, when Jerusza pulled the wide-eyed child into a town called Grajewo in northeastern Poland. And though Jerusza had explicitly told her to remain silent, Yona couldn’t seem to keep her words in. As they crept through the darkness toward a farmhouse, the girl peppered her with questions: What is that roof made of? Why do the horses sleep in a barn and not in a field? How did they make these roads? What is that on the flag?

Finally, Jerusza whirled on her. “Enough, child! There is nothing here for you, nothing but despair and danger! Yearning for a life you don’t understand is like staring at the sun; your foolishness will destroy you.”

Yona was startled into silence for a time, but after Jerusza had slipped through the back door of the house and reemerged carrying a pair of boots, trousers, and a wool coat that would see Yona through at least a few winters, Yona refused to follow when Jerusza beckoned.

“What is it now?” Jerusza demanded, irritated.

“What are they doing?” Yona pointed through the window of the farmhouse, to where the family was gathered around a table. It was the first night of Hanukkah, and this family was Jewish; it was why Jerusza had chosen this house, for she knew they would be occupied while she took their things. Now the father of the family stood, his face illuminated by the candle burning on the family’s menorah, and though his voice was inaudible, it was clear he was singing, his eyes closed. Jerusza didn’t like Yona’s ex- pression as she watched; it was one of longing and enchantment, and those types of feelings led only to ill-conceived ideas of flight.

“The practice of dullards,” she said finally. “Nothing there for you. Come now.”

Yona still wouldn’t budge. “But they look happy. They are celebrating Hanukkah?”

Of course the girl already knew they were. Jerusza carved a menorah each year from wood, simply because her mother had commanded it years before. Hanukkah wasn’t among the most important Jewish holidays, but it celebrated survival, and that was something anyone who lived in the woods could respect. Still, the girl was being foolish. Jerusza narrowed her eyes. “They are repeating words that have likely lost all meaning for them, Yona. Repetition is for people who don’t want to think for themselves, people who have no imagination. How can you find God in moments that have become rote?”

Neither of them said anything for a moment as they continued to watch the family. “But what if in the repetition they find comfort?” Yona eventually asked, her voice small. “What if they find magic?”

“How on earth would repetition be magic?” They still needed to procure a few jugs of milk from the barn, and Jerusza was losing patience.

“Well, God makes the same trees come alive each year, doesn’t he?” Yona said slowly. “He makes the same seasons come and go, the same f lowers bloom, the same birds call. And there’s magic in that, isn’t there?”

Jerusza was stunned into silence. The girl had not bested her at her own game before. “Never question me,” she snapped at last. “Now shut up and come along.”

It was inevitable that Yona would begin wondering about the world outside the woods. Jerusza had always known the time would come, and now it was heavy upon her to ensure that when the girl thought of civilization, she regarded it with the proper fear.

Jerusza had been teaching Yona all the languages she knew since she had taken her, and the child could speak f luent Yiddish, Polish, Belorussian, Russian, and German, as well as snippets of French and English. One must know the words of one’s enemies, Jerusza always told her, and she was gratified by the fear she could see in Yona’s eyes.

But she had more to teach, so on their forays into towns, she began to steal books, too. She taught the child to read, to understand science, to work with numbers. She insisted that Yona know the Torah and the Talmud, but she also brought her the Christian Bible and even the Muslim Quran, for God was everywhere, and the search for him was endless. It had consumed Jerusza’s whole life, and it had brought her to that dark street corner in Berlin in the summer of 1922, where she’d been compelled to steal this child, who had become such a thorn in her side.

And though Yona irritated her more often than not, even Jerusza had to admit that the girl was bright, sensitive, intuitive. She drank the books down like cool water and listened with rapt attention whenever Jerusza deigned to impart her secrets. By the time Yona was fourteen, she knew more about the world than most men who’d been educated in universities. More important, she knew the mysteries of the forest, all the ways to survive.

As the girl’s eyes opened to the world, Jerusza insisted upon only two things: One, Yona must always obey her. And two, she must always stay hidden in the forest, away from those who might hurt her.

Sometimes Yona asked why. Who would want to hurt her? What would they try to do?

But Jerusza never answered, for the truth was, she wasn’t sure. She knew only that in the early-morning hours of July 6, 1922, as she hurried with a two-year-old child into the forest, she heard a voice from the sky, sharp and clear. One day, the voice said, her past will return—and it will alter the course of many lives, perhaps even taking hers. The only safe place is the forest.

It was the same voice that had told her to take the girl in the first place, the voice that had always whispered to Jerusza in the trees. Jerusza had spent most of her life thinking the voice belonged to God. But now, in the twilight of her life, she was no longer sure. What if the voice in her head belonged to her alone? What if it was the legacy of her mother’s madness, a spark of insanity rather than a higher calling?

But each time those questions bubbled to the surface, Jerusza pushed them away. The voice from above had spoken, and who knew what fate awaited her if she failed to listen?

Comments are closed.