Synopsis:

Synopsis:

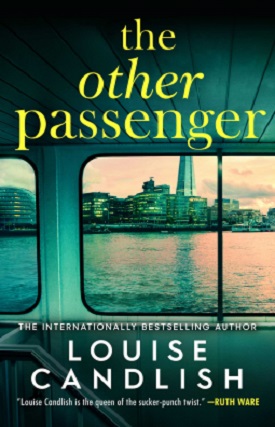

The Other Passenger focuses on Jamie Buckby, a commuter who becomes a suspect in his friend’s mysterious disappearance.

It all happens so quickly. One day you’re living the dream, commuting to work by ferry with your charismatic neighbor, Kit, in the seat beside you. The next, Kit hasn’t turned up for the boat ride to work and his wife, Melia, has reported him missing.

When you get off at your stop, the police are waiting. It seems another passenger saw you and Kit arguing on the boat ride home the previous night. And the police believe you had a reason to want him dead.

You protest. You and Kit are friends — ask Melia. She’ll vouch for you. And who exactly is the other passenger pointing the finger at you? What do they know about your lives?

No, whatever danger followed you home last night, you are innocent. Totally innocent.

Aren’t you?

Review:

Author Louise Candlish was born in Northumberland and grew up in the Midlands town of Northampton. She studied English at University College London where she continues to reside with her husband and daughter. She has penned fourteen novels, including Our House, which won the 2019 British Book Award for Crime & Thriller Book of the Year and was shortlisted for several other awards, and adapted into a four-part miniseries and Those People.

Candlish says that of all her novels, The Other Passenger was the “most enjoyable” to write because of the varied influences she was “bursting to explore,” including the 1944 classic film “Double Indemnity” starring Barbara Stanwyck. Candlish modeled the character of Melia after the femme fatale portrayed to perfection by Stanwyck. Melia is, like Stanwyck’s character, the type of “empty-hearted” woman who “effortlessly lure[s] men into their criminal plots. They look good, yes, but sex appeal isn’t enough in itself and these women also have a vulnerability that stirs a kind of warped chivalry in the men they target.” In The Other Passenger, Candlish doesn’t immediately reveal those aspects of Melia’s character . . . or the identity of her target.

She also wanted to incorporate generational conflict and credibly portrays the contrast of values between two generations, illustrating the disparities that are perceived by the characters as injustices. The disparity in her characters’ socioeconomic standing and their attitudes about their circumstances create conflict and provide motivation for the lengths to which they will go to achieve their personal goals. While some of the characters in The Other Passenger are “hurling toward fifty,” hard-working, ethical, and approach their stewardship of assets earnestly, the younger characters have a sense of entitlement and lack of morality that are shocking, especially when invoked to justify their behavior. It’s what Candlish describes as a clash between Millennials and members of Generation X.

There is responsibility and there is reward.

Candlish says she loves thrillers set on modes of transportation, especially boats, and is “particularly fascinated by commuter culture, the casual friendships that spring up between people catching the same service every day.” This aspect of The Other Passenger makes it particularly unique because the Thames Clipper (catamarans used to commute by river from East and West London into the city’s center) is a mode of transportation with which readers in other parts of the world, including the United States, are likely not familiar. It is during the commute that Kit Roper and Jamie bond after Clair and Melia bring the two couples together and the four begin socializing. The catamaran provides dramatic tension, both because other members of the public are present, passengers’ interactions are plainly visible to their fellow commuters and people on the shores who see them passing by, and a failure to board leads to questions about characters’ whereabouts and activities. Music also figures into the story, with the lyrics of songs mentioned providing clues to her characters’ “cruel intentions. . . if only the other characters will listen!” Candlish emphasizes.

As in Our House and Those People, Candlish incorporates a family home — a valuable Georgian town house by the river in which Jamie and Clare reside — which stands in stark contrast to the apartment in a rundown area for which Kit and Melia struggle to pay the monthly rent and helps to emphasize the economic disparity between the couples. Candlish explains that real estate ownership is “a crisis and an obsession that pervades every Londoner’s life.” Hence, Kit and Melia “will do anything to raise their status.”

Incorporating those elements, Candlish has crafted a clever, suspenseful, and atmospheric thriller reminiscent of not just “Double Indemnity,” but also “Body Heat,” the 1981 film starring Kathleen Turner and William Hurt. She employs a first-person narrative by Jamie that begins with an interrogation at the pier on a December morning as he attempts to board the river bus and begin his commute to his job as a barista. Kit has not shown up for the morning commute — he has gone missing, and it quickly becomes clear that Jamie has come under suspicion. They were seen fighting the previous night, and Jamie has to ensure that the bruises on his collarbone remain concealed by his sweatshirt. The detectives suggest that it was an unidentified passenger who observed Jamie engaging in suspicious behavior and reported it. But Jamie has no idea who that passenger could be. Or if the informant could be someone related to an earlier event in his life who has been stalking him.

From there, Jamie describes the events of the prior eleven months, beginning with Clare announcing that Melia has begun working at the real estate firm where Clare serves as a rental agent. Jamie and Clare’s relationship is strained because Jamie’s career imploded after what he describes as a “mental health episode suffered a year and a half ago among total strangers” and he has not made satisfactory efforts to resurrect it, in Clare’s estimation. They live in that aforementioned Georgian town house that actually belongs to her parents — they bought it in the 1980’s before gentrification made it a sought-after location. Kit and Melia are would-be actors struggling to pay the bills with Kit toiling at an insurance brokerage. They have unpaid student loans, have defaulted on credit card payments, overdrawn their bank accounts, been evicted, and owe overdue rent for their new residence. “Their salaries barely touch the sides of the money pit.”

Candlish deftly reveals the conflicts in the four characters’ relationships that develop over time. Clare wants Jamie to take advantage of the opportunities she has afforded him to get his life back on track, utterly unable to understand why the former marketing executive seems content working a dead-end job far below the professional standing he previously enjoyed. She is anxious for him to become her equal in every way. Jamie is happy to reap the rewards of Clare’s privilege (they live in that beautiful home rent-free), but emasculated by his understanding that he must sufficiently placate Clare to avoid becoming homeless. “The truth was that by leaving my white-collar career I’d rendered myself as economically helpless as the Ropers.” He is gradually unmasked as a man who is not as principled as he initially seems — a liar who deceives Clare in order to maintain the status quo, justifying his mistakes because he has “to grovel.” Candlish injects jaw-dropping revelations at expertly-timed junctures, compelling the story forward at a steady pace.

Envy plays heavily into the plot as Melia and Kit openly long for and not-so-secretly resent the lifestyle Clare and Jamie enjoy. Jamie, Kit, and Melia characters are, in varying degrees, duplicitous and willing to form alliances and double-cross each other to attain the standard of living to which they aspire without having to earn it. One character is particularly hapless and gullible, failing to observe and heed the clues that Candlish simultaneously presents to him and readers, at his own peril. As the story progresses, allegiances shift, secrets are disclosed, theories proffered and discarded, and those generational divides, coupled with old-fashioned morality, prove to be impactful. Candlish incorporates astute observations about the difficulty young adults face as they emerge from college burdened by student loan debt and find home ownership an elusive dream.

The Other Passenger is a tautly-crafted, character-driven thriller. Replete with with surprising plot twists, the contemporary setting and relatable struggles Candlish’s characters confront enhance its believability, making it thoroughly entertaining.

Excerpt from The Other Passenger

Chapter 1

December 27, 2019

Like all commuter horror stories, mine begins in the mean light of early morning — or, at least, officially it does.

Kit isn’t there when I get to St Mary’s Pier for the 7:20 river bus to Waterloo, but that’s not unusual; he’s had his fair share of self-inflicted sick days this festive season. An early morning sailing calls for a strong stomach at the best of times, but for the mortally hungover it’s literally water torture (trust me, I know). In any case, he always arrives after me. Though we live just five minutes apart and he passes right by Prospect Square to get to the pier, we gave up walking down together after the first week, when his spectacularly poor timekeeping — and my neurotic punctuality — became apparent.

No, Kit prefers to stroll on just before they close the gangway, raising his hand in greeting, confident I’ve secured our preferred seats, the portside set of four by the bar. At St Mary’s, boarding is at the front of the boat and so I’ll watch him as he moves down the aisle, hands glancing off the metal poles—as much for style as balance—before sliding in next to me with an easy grin. Even if he’s been up late partying, he always smells great, like an artisan loaf baked with walnuts and figs (“Kit smells so millennial,” Clare said once, which was almost certainly a criticism of me and my Gen X smell of, I don’t know, stale dog biscuits).

Get us, he’ll say, idly scanning the other passengers, snug in their cream leather seats. It’s one of his catchphrases: Get us. Pity the poor saps crushed on the overland train or suffocating on the Tube—we’re commuting by catamaran. Out there, there are seagulls.

Also, sewage, I’ll reply, because we’ve got a nice sardonic banter going, Kit and me.

Well, we used to.

I clear the lump in my throat just as the boat gives a sudden diesel rumble, as if the two acts are connected. On departure, information streams briskly across the overhead screens — Calling at Woolwich, North Greenwich, Greenwich, Surrey Quays — though by now the route is so imprinted I pay little attention. Through the silver sails of the Thames Barrier and past the old aggregate works and industrial depots of the early stretch; then you’re at the yacht club and into the dinghy-strewn first loop, the residential towers of the peninsula on your left as you head towards the immense whitehead of the O2 Arena. Strung high above the river is the cable car that links the peninsula to the Royal Docks, but I won’t allow myself to think about my only trip to date on that. What was done that night. What was said.

Well, maybe just briefly.

I turn my face from the empty seat beside me, as if Kit is there after all, reading my mind with its secret, unclean thoughts.

“Back again on Friday,” he grumbled on the boat on Monday night, bemoaning his firm’s insistence on normal working hours for this orphan weekday between Boxing Day and the weekend. “Cheapskates.” Normally, if he misses the boat, I’ll text him a word or two of solidarity: Heavy night? Maybe some beer emojis or, if I was involved in the session, a nauseated face. But I don’t do that today. I’ve hardly used my phone since before Christmas and I admit I’ve enjoyed the break. That old-school nineties feeling of being incommunicado.

We’re motoring now past the glass steeples of Canary Wharf towards Greenwich, the only approach that still has the power to rouse my London pride: those twin domes of the Old Royal Naval College, the emerald park beyond. I watch the bar staff serve iced snowflake cookies with the teas and coffees—it’s surprising how many people want to eat this stuff first thing in the morning, especially my age group, neither young enough to care about their silhouette (such a Melia kind of word) nor close enough to the end to give a damn about health warnings. Caffeine and sugar, caffeine and sugar: on it goes until the sun is over the yardarm and then, well, we’re all sailors in this country, aren’t we? We’re all boozers.

Only when we dock in front of the Cutty Sark do I finally reach for my phone, reacquaint myself with my communications of Monday night and the aftermath of the water rats’ Christmas drinks. I scan my inbox for Kit’s name. My last text to him was spur-of-the-moment and tellingly free of emojis:

Just YOU wait.

Sent at 11:38 p.m. on Monday, it’s double-ticked as read, but there has been no reply. There have been, however, five missed calls from Melia, as well as three voicemails. I really should listen to them. But, instead, I hear Clare’s voice from yesterday morning, the “proper” talk we had under a gunmetal northern sky four hundred miles from here:

You need to cut ties.

Not just him, Jamie. Her, as well.

There’s something not right about those two.

Now she tells me. And I slip the phone back in my pocket, buying myself a few extra minutes of innocence.

At Surrey Quays, Gretchen gets on. The only female water rat, she’s prim in her narrow, petrol-blue wool coat, carrying one of those squat bamboo cups for her flat white. Though I’m in our usual spot, she settles in the central section several rows ahead. Weird. I move up the aisle and drop into the seat next to her. You can’t usually take your pick so easily on the 7:20, but the boat is half empty—even excusing the lucky bastards who don’t have to return to work till the New Year, I have to admit the river’s no place to be in these temperatures. It’s one of the coldest days of the year, breath visible from people’s mouths on the quayside and from the heating systems of the buildings.

“Jamie, hi,” she says, not quite turning, not quite smiling. Her lashes are navy spider’s legs and there’s a feathering of pink in the whites of her eyes.

“Thought you were blanking me there,” I say, cheerfully. “Good Christmas with your family?” She’s been somewhere like Norwich, if I remember. There are healthy, uncomplicated parents, a brother and a sister, a brace of nieces and nephews.

She shrugs, sips her coffee. “It’s all about the kids, isn’t it? And I haven’t got any.”

There’s really no need for her to spell this out: we’re connected, our little group, by our childlessness, our freedom to put ourselves before everyone else. To self-indulge, take risks. No parent would do what I’ve done this last year, or at least not so readily, so heedlessly.

“What about yesterday? Do any sales shopping?”

Gretchen blinks, surprised, like I’ve suggested she rode a unicorn naked down the middle of Regent Street. She’s clear-skinned, delicately feminine, though in temperament a woman who likes to be one of the boys, who laments the complexities of her own gender and thinks men simpler allies (a dangerous generalization, in my opinion).

“You all right, Gretch?”

“Yeah, just a bit tired.”

“I don’t know where Kit is this morning. I’m sure he said he was working today. Did he say anything to you?”

“Nope.” There’s an edge to her tone I’m familiar with, a peculiarly female strain of pique. I’ve wondered now and then if there might be something between Kit and her. Maybe there was some indiscretion on Monday night, maybe she worries what I saw. Did I say something I shouldn’t have? God, the “shouldn’t haves” are really building: shouldn’t have got so drunk, shouldn’t have let him goad me.

Shouldn’t have sent him that last text.

“What happened there?” she asks, noticing my bandaged right hand.

“Oh, nothing major. I burned my thumb at work. Didn’t I show you on Monday?”

“I don’t think so.” Noticing the music piping through the PA—the same loop of festive tunes we’ve been subjected to since early December—Gretchen groans. “I can’t take any more of this ‘happy holidays’ crap, it’s so fake. You know what? I think I might just book a trip somewhere sunny. Call in sick for a few days and get out of here.”

“Could be expensive over New Year.”

“Not if I go somewhere the Foreign Office says is a terrorist risk.”

I raise an eyebrow.

“Anyway,” she adds, “what’s another grand or two when you’re already in the red?”

“True.” But I don’t want to talk about money. Lately, it’s the only thing I hear about. We pass the police HQ in Wapping, close to the zone change at which the westbound boats are required to reduce speed precisely as passenger impatience starts to build. We’re entering the London the world recognizes—Tower Bridge, the Tower of London, the Shard—and as the landmarks rise, Gretchen and Kit and their troubles sink queasily from my mind.

“Enjoy Afghanistan, if you go,” I say, when she prepares to disembark at Blackfriars for her office near St Paul’s.

She smiles. “I was thinking more like Morocco.”

“Much better. Let us know.” My joker’s grin shrinks the moment the doors close behind her and I rest my cheek on the headrest, stare out of the window. Seven fifty in the morning and I’m already done in. The water is high as we sail towards Waterloo, sucking at the walls with its grimy brown gums, and the waterside wonderland of lights that glows so magically after dark is exposed for the fraudulent web of cables that it is. It’s as quick to get off at Westminster Pier and walk across the bridge as it is to wait for the boat to make a U-turn and dock at the Eye, but I choose to sit it out. I hardly register the pitch and roll that once threw me into alarm or, for that matter, the great wheel itself, its once miraculous-seeming physics. Disembarking, I ignore the waiting ticket holders and stroll up the causeway with sudden sadness for how quickly the brain turns the wondrous into the routine: work, love, friendship, traveling to work by catamaran. Or is it just me?

It’s at precisely that moment, that thought—right on the beat of me—that a man steps towards me and flashes some sort of ID.

“James Buckby?”

“Yes.” I stop and look at him. Tall, late twenties, mixed race. Business-casual dress, sensitive complexion, truthful eyes.

“Detective Constable Ian Parry, Metropolitan Police.” He presses the ID closer to my face so I can see the distinctive blue banner, the white lettering, and straightaway my heart pulses with a horrible suction, as if it’s constructed of tentacles, not chambers.

“Is something wrong?”

“We think there might be, yes. Christopher Roper has been reported missing. He’s a good friend of yours, I gather?”

“Christopher?” It takes a moment to connect the name to Kit. “What d’you mean, missing?” I’m starting to tremble now. “I mean, I noticed he wasn’t on the boat, but I just thought…” I falter. In my mind I see my phone screen, alerts for those missed calls from Melia. Her heart-shaped face, her murmured voice humid in my ear.

We’re different, Jamie. We’re special.

The guy gestures to the river wall to my left, where a male colleague stands apart from the tourists, watching us. Plainclothes, which means CID, a criminal investigation. I read somewhere that police only go in twos if they think there’s a risk to their safety; is that what they judge me to be?

“Melia gave you my name, I suppose?”

Not commenting, my ambusher concentrates on separating me from the groups gathering and dispersing at the pier’s entrance, owners of a hundred purposes preferable to my own. “So, if we can trouble you for a minute, Mr. Buckby?”

“Of course.” As I allow myself to be led towards his colleague, it’s the coy, old-style phrasing I get stuck on. Trouble you for a minute, like trouble is a passing trifle of an idea, a little Monday-morning fun.

Well, as it transpires, it’s neither.

Comments are closed.