Synopsis

Synopsis

“My land tells its story if you listen. The story of our family.”

Texas, 1921. It’s a time of abundance. The Great War is over, the bounty of the land is plentiful, and America is on the brink of a new and optimistic era.

But Elsa Wolcott is deemed by her family to be too plain and too old to marry. And marriage is a woman’s only option. So her future looks bleak. Until the night she meets Rafe Martinelli and decides to change her destiny. Soon her reputation is ruined and but one respectable choice remains: estrangement from her family and marriage to a man she barely knows.

By 1934, the world has changed. Millions of Americans are out of work and standing in bread lines for food. Drought has devastated the Great Plains. Farmers are fighting to keep their land and their livelihoods, but crops fail, and water dries up, causing the earth to crack open. Dust storms roll relentlessly across the plains. The country is in crisis and the land itself seems to have turned against its citizens.

Everything on the Martinelli farm is dying, including Elsa’s tenuous marriage. Each day is a desperate battle against nature and a relentless fight to keep her children alive.

The uncertain, perilous times, and the well-being of her precious children force Elsa, like so many others, to make an agonizing choice. She can stay in Texas and fight for the land she has come to love . . . or leave it behind and go west to California in search of a better life for her family.

In The Four Winds, bestselling author Kristin Hannah paints an unforgettable portrait of America during the Great Depression and the American dream as seen through the eyes of Elsa, an indomitable woman whose courage and sacrifice will define a generation.

Review:

Growing up, I heard the story primarily from my mother. It unfolded on a farm just outside Kidder, South Dakota, a tiny town that ceased to exist altogether sometime in the 1960’s.

When my great-grandfather homesteaded in Dakota Territory in 1882, leaving his wife and my one-year-old grandmother back in Norway until he could save enough money to bring them to America, the farm consisted of 160 acres. At some point, the United States government took back three acres through the process of eminent domain. From then on, the railroad tracks traversed part of those three acres and from time to time, my grandmother fed a hobo or two who hopped off a passing train and showed up at the front door. At least one stayed for a time, bunking in the barn, and helping work the land before deciding it was time to move on. I’ve forgotten the name of the one who stayed the longest and became like part of the family for awhile. No one knew where he ended up or what became of him.

My mother talked about going into town with my grandmother to sell eggs and use the money to buy other groceries. My grandfather grew wheat, but never owned a tractor, much less a combine. He loved his horses — the faster they ran, the better — and enlisted my mother to go with him to his brother’s house to cap the bottles of beer they brewed there. Sometimes he went to Uncle Louie’s house alone, imbibed too much, and it fell to her and Grandma to get him into bed to sober up, while her two older brothers took care of the horses. The stress of trying to survive in the Dust Bowl was surely too much for a proud, hard-working man who teetered on the verge of losing the family farm.

But my grandparents did manage to hold on to the farm. Just barely. Many of their friends and neighbors were not so fortunate. And the memories of those nights ensured my mother would never be a drinker . . . or marry one.

I also heard about the evenings when supper consisted only of “milk soup” — warm bowls of milk and bread. They made bread using the wheat they grew, and the cows provided milk. So they didn’t starve. But there was no plumbing or electricity in that two-story wooden farmhouse that was originally a sod hut.

Nor was it insulated. And when the dust storms came, they were fierce. The dust blew right into the house, coating everything in its path. My mother described waking up covered in it and looking down at a white outline of her head on the fabric of her pillowcase — the only clean area of the cloth. She also recalled how the scorching sun beat down on her as she sat on the fence by the railroad tracks after herding the cattle toward any grass she could find for them to graze on, praying for rain.

A brilliant woman, she graduated from high school in 1934 with dreams of going to college. She tried everything she could think of to secure the required funds, but there simply wasn’t any money to be had or borrowed. Instead, she worked as a combination housekeeper, cook, and babysitter for a local family for which she earned two dollars per week.

Her cousin introduced her to my father. He grew up in the nearby little town of Newark that disappeared from the landscape well before Kidder. He graduated from the eighth grade and then, one of eight children, had to drop out of school and go to work because his parents did not have the means to support the whole family. He worked wherever he could, at one point hitchhiking with a friend to Los Angeles where he spent several months trimming trees before heading back to South Dakota and resuming work as a farmhand.

So the subject matter addressed in The Four Winds immediately intrigued me. And author Kristin Hannah drew me right into the story with a Prologue that could easily have been penned by and about the women in my own family: “The land we loved turned on us, broke us all, even the stubborn old men who used to talk about the weather and congratulate each other on the season’s bumper wheat crop. A man’s got to fight out here to make a living, they’d say to each other. A man. It was always about the men. They seemed to think it meant nothing to cook and clean and bear children and tend gardens. But we women of the Great Plains worked from sunup to sundown, too, toiled on wheat farms until we were as dry and baked as the land we loved. If I close my eyes sometimes, I swear I can still taste the dust . . . ” Those words are eerily akin to those I heard my mother voice in an effort to make me understand how privileged, in comparison to hers, my upbringing was.

Like me, Hannah was an attorney before she turned to writing fiction. In fact, it was her mother who told her not to worry about her classes because “you’re going to be a writer anyway.” She says there are many stories about men heroically overcoming adversity, but finds it important “to put women back into that landscape.”

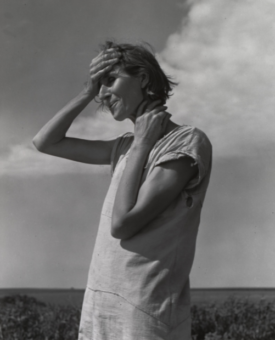

She was inspired to craft The Four Winds by the work of Dorothea Lange, an American documentary photographer and photojournalist, particularly her portrait “Woman of the High Plains.” Hannah says that in the photo she could see the woman’s desperation and fear, but “there was this strength in her that spoke to me.”

The story opens in 1921 in Dahlhart, Texas, on the eve of Elsa Woolcott’s twenty-fifth birthday. She has spent “years in enforced solitude, reading fictional adventures and imagining other lives.” She knows she has “always been an outsider in her own family,” even though they blame her circumstances on the childhood illness she survived. She also knows — and they have reinforced — that she is not pretty. She is tall, pale, thin, and lacking self-confidence, but determined to have a meaningful life, rather than merely exist. And she naively believes she might be able to fulfill that dream when she meets Rafe Martinelli, a young man from a proud Italian family who is bound for college and engaged to another young woman. Elsa believes she has found love, but soon discovers how little she knows about life and the world. When her relationship with Rafe can no longer remain hidden, she is disowned and abandoned by her own family, and Rafe’s college plans are scuttled. But before they marry, Elsa asks if Rafe’s parents, Rose and Tony, will love her child. When Rose declares, “The baby, I will love. My first grandchild,” Elsa knows that for the sake of her child, she will become part of a disappointed family that doesn’t want her.

Rose and Tony gradually take Elsa, along with her daughter, Loreda, and son, Anthony (“Ant”), into their hearts. Rose teaches Elsa how to cook and tend to a home, and Elsa tries to hold her marriage together as her love for her in-laws, the land, and the true home she has come to know, grows.

But by 1934, the family has endured four years of drought. Coupled with the stock market crash in 1929 and ensuing Depression, they are barely surviving. Their wheat crops have failed, the well is drying up, and Rafe is increasingly miserable . . . and drinking. The dust storms begin, obliterating everything in their path, including the vegetables they have managed to grow in their garden. They console themselves with the belief that so long as cows and chickens thrive, they can get by selling milk and eggs.

The four winds have blown us here, people from all across the country, to the very edge of this great land, and now, at last, we make our stand, fight for what we know to be right. We fight for our American dream, that it will be possible again. ~~ Elsa

Hannah compellingly and unsparingly relates the family’s increasingly dire circumstances. Her descriptions of the brutal dust storms are realistic and terrifying. She convincingly depicts teen Loreda’s growing anger and resentfulness, as well as the desperation that inevitably overtakes Elsa, Tony, and Rose. They watch as their neighbors begin losing their land via foreclosure or selling it off for any price, along with their possessions, and leaving their Texas homes in search of better living conditions. Many head to California, some to Oregon.

But the Martinellis remain convinced that they can, quite literally, weather the storms and rain will come, bringing solutions to their problems. It doesn’t. Things continually get worse until there is no choice to be made. Silicosis — dust pneumonia — threatens Ant’s life. The doctor explains, “Prairie dust is full of silica. It builds up in the lungs and tears away the air sacs. He’s breathing in dirt and swallowing it. Filling up with it.” The boy literally cannot breathe. “Dust pneumonia. That was what they called it, but it was really loss and poverty and man’s mistakes,” Hannah writes.

Hannah’s portrayal of Elsa’s dangerous journey west to California, where she believes she will be able to make a decent home for herself and her children, is gut-wrenching, suspenseful, and heartbreaking. Elsa’s grit and focus compel her as she navigates the dangerous route with her children in tow. The harrowingly disappointing realities she confronts when they arrive in the Golden State are even more devastating. It is far from the “land of milk and honey” promised in the flyer a neighbor pressed into Rafe’s hand, declaring, “Jobs for everyone! Land of opportunity! Go West to California!” Californians do not welcome those migrating from the Dust Bowl, instead taking full advantage of them and forcing them to barely eke out an existence in deplorable and inhuman living conditions. Elsa soon realizes that she has brought her children to an environment even worse than the one they escaped in Texas. But in the migrant camp where they take up residence, she does find a friend upon whom she can rely, and the way the women help and support each other is one of the most beautiful and tragic aspects of the story. That friendship profoundly impacts Elsa and the choices she ultimately makes.

The Four Winds is an engrossing work of historical fiction at the center of which is the memorable and inspiring Elsa, a woman who finds strength she never knew she possessed and summons it in order to protect the two things in the world that matter most: her children. Made to believe that she was unworthy of love by her own family, Elsa learned as a child to be invisible in her own home. And as she enters into marriage with Rafe, she does so intending to remain invisible. But she is transformed once she becomes a mother and as merely staying alive becomes more challenging with each new day. As is her daughter, who finds her own strength as she gradually stops blaming Elsa for every horrible thing she has experienced and observes the lengths to which her mother will go in order to protect her and her brother.

Hannah does not shy away from exploring, through her characters’ experiences, how America created and responded to the Great Depression. She depicts the struggles between classes, especially once Elsa and her children arrive in California. Migrants are denied medical care and education. Elsa and other workers are taken advantage of by wealthy landowners who hire laborers to pick cotton under terms that ensure they will never be independent. In order to secure a place to live and be able to feed her children, Elsa is forced to accept credit, but it creates a cycle from which she cannot escape. She must rely on more credit during the winter months when there are no crops to pick in order to pay off the prior year’s balance, unable to ever escape the cycle. Union organizers bring hope for better working and living conditions, along with danger to the camps. Elsa finds herself in the midst of the controversy and realizes that her grandfather was right when he told her so many years earlier that it isn’t fear that matters in life. It’s the choices you make when you are afraid. Elsa’s journey and experiences lead her to conclude that she has to be a warrior for her children because that’s what motherhood requires. And she has to tangibly model for them the lesson her grandfather taught her. It’s a life-changing decision.

The Four Winds is an epic tale of power, strength, survival, and how far love can and will carry a determined woman who envisions a meaningful life for herself and her children. In Hannah’s capable telling of Elsa’s story, love carries her through and out of unimaginable despair and hopelessness, and permits her to leave her children an enduring legacy devotion and resilience. Because, as Elsa learns, “Love is what remains when everything else is gone.”

Hannah says that she began writing historical fiction out of a “desire to return women to their lost stories in history, put them at the center of the action, and make them the heroes.” Elsa is Hannah’s favorite character to date because she transforms from an insecure woman who, at the outset, doesn’t believe she is worthy of love or has a vibrant future, progressing primarily as a result of becoming a mother into “a warrior woman who is able to fight not only for herself and her children, but finally finds a voice strong enough to speak for people who are too afraid to speak for themselves.” Hannah describes fictional Elsa as “representative of thousands of brave women who went west in search of a better life.” But in actuality, she represents all the women, including those in my own family, who persevered and never gave up during the dark days of the Great Depression in order to ensure that their children’s futures were brighter than their current circumstances. My family did not come to California until June 1957, when I was six months old, so we were not part of the great migration out of the Dust Bowl. But the women in my family were indeed as resilient and strong as Elsa, a heroic character that readers will embrace and remember fondly long after they finish reading The Four Winds.

Also by Kristin Hannah:

Comments are closed.