Synopsis:

Synopsis:

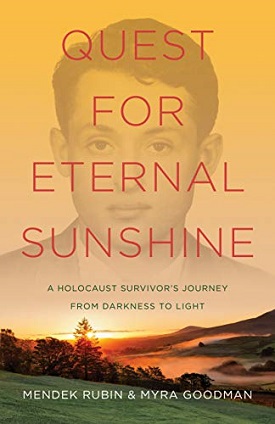

Mendek Rubin was born into a Hassidic Jewish family in Poland in 1924. He grew up surrounded by extreme anti-Semitism. Armed with an ingenious mind, he survived three horrific years in Nazi slave-labor concentration camps while nearly his entire family was murdered in Auschwitz.

Mendek arrived in America in 1946 at the age of 21 with a sixth-grade education, and no money or professional skills. He did not speak English. Nonetheless, over the next forth years, his inventions helped revolutionize the jewelry and packaged-salad industries.

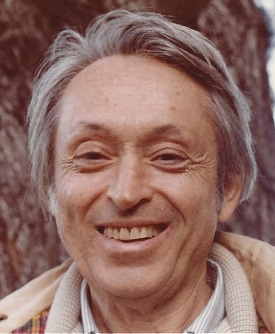

Mendek also applied his ingenuity to his own psyche, developing innovative ways to heal his heart and end his emotional suffering due to unrelenting depression. After his death in 2012, his daughter, Myra Goodman, found an unfinished manuscript. In his writings, he revealed the intimate details of his pain and his journey to healing, wholeness, and joy.

The result is an extraordinary posthumous father-daughter collaboration relating Mendek’s story, and his discovery and application of effective self-healing techniques that transformed his life.

Review:

Mendek grew up in the little town of Jaworzno, Poland, where Jews were the minority and disparaged. Most of the Jews were merchants in a town that was largely supported by five coal mines. Mendek’s family lived in the center of town, the son of a Talmud scholar who was disappointed that Mendek did not display an equal aptitude for his studies due to dyslexia. Mendek “felt like a disgrace and lived in fear of [his] father’s wrath.” Mendek had one brother and four sisters. Because Jaworzno was close to the German border, it was one of the first to be occupied when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. His aunt hid textiles from her store before the Germans took it over, and his family survived by smuggling those textiles to a Christian grocer to trade for food. Mendek was required to work in a coal mine and describes watching a group of two hundred Jews of all ages walking along the highway “in total silence, escorted by German soldiers carrying machine guns.” As he watched them, he knew they were walking to their death. Later, he learned they were walking to Auschwitz, situated fifteen miles away, but he did not yet understand “that the systematic extermination of all the Jewish people in Poland had begun.” But his observation of that walk haunted him for many years because he turned his rage, helplessness, and humiliation

inward.

A few weeks later, in May 1942, each Jewish family was required to select one member to go to work in a labor camp. To spare his parents from making the choice, Mendek volunteered and, at the age of seventeen, he was forcibly taken by armed guards to a concentration camp. It was the first of seven camps in which he would spend the next three years. He saw his parents standing on a side street, and describes meeting their eyes and feeling “their love and concern for me.” He passed by them in silence on his way to the railroad station. “It was the last time I ever saw them.” Mendek was certain that most of his family would perish, and “felt guilty to wanting to live. My selfishness was a constant weight upon me during those three long years.”

Mendek lived a “marginal existence,” never resuming the practice of the religious beliefs and rituals that defined his life before the war, and feeling guilty about it. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and served during the Korean War. Like so many soldiers, he was given aptitude tests that revealed his mechanical abilities. After his discharge he began working for free in a jewelry manufacturing company where he devised a way to mechanize setting stones in rings and soldering them into place. He parlayed that into a successful business and, later, figured out how to mechanically stamp clasps for bracelets. Along with his cousin, Simon Geldwerth, he formed Do-All Jewelry in 1954, and operated it for many years. At the age of thirty-seven, he met and married Edith, a fellow Holocaust survivor, and they had two daughters, Ruthie and Myra.

Despite his thriving business and adoring family, Mendek spent years suffering from guilt and depression. Although he enjoyed good times, he “carried a nagging feeling of emptiness, as if a dark cloud constantly hovered over” him. Edith also struggled with intermittent depression.

I did not consciously choose my journey. What was within me simply exerted a pull I could not resist. . . . I was never sure of my destination until I discovered the power of love.

So Mendek commenced a journey to find relief. The bulk of Quest for Eternal Sunshine is devoted to his description of the various methodologies he employed in his determination to experience true joy and peace. He describes his experiences with hypnotherapy and Freudian therapy, as well as his study of psychology. In the 1960’s and 1970’s, encounter groups were popular, and Mendek and Edith immersed themselves in them. Eventually, they found their way into a group known as the Pathwork in which a woman named Eva Perrakos allegedly channeled a spirit referred to as the Guide. For years, they spent every spare moment studying and interacting with the cult-like group which claimed to practice Core Energetics. Mendek explains that it felt “authentic” to him “at the time.” For the first time, he felt free and discovered his joy of writing, memorializing poems, affirmations, and revelations in an effort to access his “Higher Self.” Eventually, they even took up residence in the group’s compound, but left when they became disillusioned. Mendek longed to break out of the decades he had spent “wallowing” in self-pity as a result of what he suffered.

Mendek’s pilgrimage to enlightenment also included meditation, painting, and “a wide variety of spiritual teachings.” In 1982, they abruptly left New York and moved to Carmel, California when they fell in love with California and decided that they wanted to live near the ocean. He sold the jewelry business and retired, but continued his quest to resolve the conflict he still felt. He describes being “plagued by a nagging inner hunger I didn’t know how to appease.” Periods of respite gave way to unhappiness and he was preoccupied with the workings of his mind. Eventually, through ongoing study and experimentation with visualization, affirmations, and getting in touch with the child he once was, Mendek came to grips with his childhood and feelings of rejection by his father. He began to remember happier times and events, and accepted that he was just a little boy “who craved love, security, and acceptance” and that little boy still lived inside him. He came to understand that his parents loved him but were defined by the extreme circumstances of the time, and learned to love his imperfect self. By re-envisioning his past, he confirmed that it was not “etched in stone.”

Ultimately, Mendek found true joy by repeating “I choose to believe. I choose to believe. I choose to believe.” He experienced an epiphany: He decided “to always have faith in the limitless power of love.” And he overcame his survivor’s guilt when he realized that he was, in fact, lucky. “I saw that every time I should have died in the past, something happened to save my life. . . .I realized that I was one of the luckiest guys alive.”

Quest for Eternal Sunshine is written in straight-forward, easy-to-read language. It is a fascinating and deeply moving story about a man who, like so many others, was born at a time in history and a place where he was destined to endure unspeakable cruelty and witness indescribable atrocities, and yet, miraculously, survive. Nonetheless, for decades he was unable to embrace his good fortune, particularly because his home, neighbors, and family (with the exception of Bronia) perished. The term post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was coined in the 1970’s and accepted by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980. It is likely that Mendek and Edith both suffered from PTSD as a result of all they endured, but formal treatment (hypnotherapy and Freudian therapy) did not provide Mendek relief. Rather, Quest for Eternal Sunshine details Mendek’s determination to work his way through the mysterious workings of his own mind in order to find lasting peace. The book is an homage to him by his admiring daughter, Myra, and a tangible testament to his character, as well as his intellect, unwavering fortitude, and willingness to absorb and learn from frequently unpleasant truths about himself that he discovered through his exploration. Perhaps most astonishing was his capacity to forgive — not just his captors, but also himself and his “people for accepting our fate so meedly, without a struggle. I felt we’d been cowardly, which angered and frustrated me.” Ultimately, however, he realized and accepted that nothing he or his people could have done would have altered the outcome, bathing himself in “tenderness and absolute acceptance!”

Eventually, Mendek committed to always being present in the moment because he found that “[p]resence is where peace lives.” Mendek understood that he was an everyman and the lessons he shares in Quest for Eternal Sunshine are relevant to and can be employed by anyone who has experienced trauma and suffered in its aftermath.

Enter to Win a Copy of Quest for Eternal Sunshine

NOTE: The book may only be mailed to a United States address.

6 Comments

a story to learn from

One of my favorites is The Diary of Anne Frank. I read this when I was young and it made such a strong impact on me, and has stayed a favorite for decades.

I have read hundreds of Holocaust memoirs and non-fiction. Every one of the books is meaningful, profound, emotional, and unforgettable. Being Jewish I am interested in how the individuals survived and then lead productive and happy lives. People are interested in learning how their courage, luck, and strength of character allowed them to survive the torture of many years. I read The Lucky Child by Thomas Buergenthal, A life Rebuilt by Sylvia Ruth Gutmann, The Seven by Ellen G. Friedman and many others. Thanks for this wonderful feature and giveaway.

I have read many Holocaust books and one of my favorites was The Nightingale.

I have read many Holocaust books, but Night by Elie Wiesel, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Echoes from Auschwitz: Dr. Mengele’s Twins: The Story of Eva and Miriam Mozes by Eva Mozes Kor were especially impactful. I also had the privilege of hearing Eva Mozes Kor speak in person about her experiences as she and her twin sister were experimented with by Josef Mengele at Auschwitz. That was something I will never forget. I think people are not only interested in reading about this part of history to remember the strength of human character of those that suffered and survived the camps, but also to remember those lost. May keeping these stories alive help prevent such a horrible thing from ever happening again!

The only one I can think of is The Diary of Anne Frank. I think that it’s a fascinating subject for many because it’s barely believable that such a horrific tragedy on that scale could have possibly happened.