Synopsis:

Synopsis:

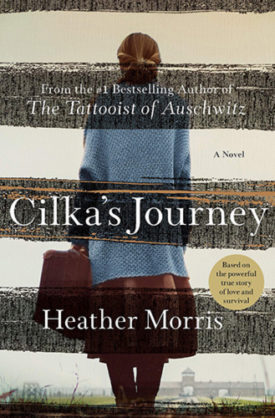

Cilka’s Journey is a novel based upon the true story of a woman whose beauty saved her . . . and condemned her.

In 1942, Cilka is just sixteen years old when she is taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. Unlike other female prisoners, she is not required to shave her head. Instead, because the commandant immediately notices how beautiful she is, her long, flowing tresses remain. And stand out. She is separated from the other prisoners — singled out by a powerful Nazi officer — and learns quickly that power, even unwillingly surrendered, equals survival.

When the war is over and the camp is liberated, Cilka is cruelly denied freedom. Instead, she is convicted of collaborating with the Nazis because of what she was forced to do, and sentenced to serve fifteen years in a Siberian gulag (prison camp).

Did she really have a choice? And where do the moral lines fall for Cilka, who was sent to Auschwitz when she was essentially still a child?

In Siberia, Cilka faces challenges both new and horribly familiar, including the unwanted attention of both guards and male prisoners. But a kind female doctor takes Cilka under her wing, giving her a job in the camp hospital. Cilka tends to the ill prisoners, struggling to care for them under brutal conditions.

Confronting death and terror daily, Cilka finds strength she never knew she possessed. When she forms tentative bonds and forges relationships in her harsh, new surroundings, Cilka discovers that, despite everything that has happened to her, there is room in her heart for love.

Cilka’s journey from child to woman, and from woman to healer illuminates the resilience of the human spirit — and the will we all possess to survive.

Review:

Author Heather Morris introduces readers to Cilka in The Tattooist of Auschwitz. The beautiful young girl is working quietly in the administration building when she is dragged away from her desk by two SS officers and thrown into a room furnished with a bed and dresser where Schwarzhuber, the head of Birkenau is waiting for her. Cilka quickly understands what is expected of her. Resistance would cost her her life. For the remainder of her time in the camp, she is ridiculed by some prisoners as Schwarzhuber’s “plaything,” but all understand the cost of survival. None better than the tattooist himself, Lale Sokolov, who later declared Cilka “the bravest person I ever met.”

When the camp is liberated in January 1945, Cilka’s nightmare does not end. As Cilka’s Journey begins, she has been in the custody of the Soviet Army for several weeks. Only eighteen years old, she is dragged out of the cell block for questioning, but hopeful “they can see that she had no choice but to do what she did in order to survive. No choice, other than death.” She dreams of making her way home to Czechoslovakia. In response to questioning about whether she prostituted herself to the enemy, she says, truthfully, “They were my enemy. I was a prisoner here. Like many others here, I was forced to do whatever I was told by those who imprisoned me. I was forced, I was raped.” Instead of being treated with compassion, she is transferred to a prison in Krakow where, in July 1945, she is informed of her fate. “You are convicted of working with the enemy as a prostitute and additionally as a spy. You are sentenced to fifteen years hard labor.”

Thrust onto a train bound for Vorkuta Gulag, Siberia, with other female prisoners, Cilka’s journey to more suffering begins. She curses herself for indulging “just one moment of hope” and ponders whether punishment is what she truly deserves. She soon discovers that many of the other women are also being punished for “crimes” of survival such as operating a bakery in Poland that sold bread to Nazis. Still, Cilka keeps her past a secret, fearful of being judged and ostracized — or worse — by the other women. She befriends a young girl, Josie, who reminds her of her friend Gita, Lale’s beloved. Just sixteen, Josie is traveling with her grandmother and Cilka knows that the naive teenager needs guidance.

Cilka remains by Josie’s side as they arrive at and are processed into the camp and housed together in a bunker with several other women. They forge a friendship that will forever change both of them. They have been sentenced to hard labor and Cilka wonders if knowing the end date, unlike during her last imprisonment, will make it more endurable. Assuming that she can even believe the end date is accurate. Regardless, she knows from experience that in order to survive she will have to advance her status in the camp, as well as Josie’s, without drawing attention. “Or maybe she is here because of thoughts like that. Maybe hard labor is what she deserves.”

We were faced only with impossible choices.

Morris relates Cilka’s experiences and details the relationships she develops in the prison, interspersing the current narrative with Cilka’s memories both of her happy childhood with her family and her days in Auschwitz-Birkenau. She is depressed and hopeless, finding herself punished for what she has already endured. But her will to live is strong and will not be diminished. She persists, often letting anger carry her forward. But always guarding her emotions and the truth about her past.

She comes to the attention of Doctor Kalani, Yelena Georgiyevna, who has volunteered to be assigned to the camp hospital in an effort to help improve conditions there. She offers to train Cilka to work as a nurse, and Cilka sees the opportunity as a way to help her fellow prisoners, women with whom she has come to share affection and a bond. “She carefully grants days to the sick and infirm that she never could, in her old life. Though in all of these places it is always one person for another. One person’s comfort, one person’s food. Nothing is fair.” Especially when Cilka finds herself punished for saving a man’s life.

Her benevolence extends to Hannah, who is blackmailing her — demanding that she steal medicine from the hospital in exchange for keeping her secret. She desperately wants to explain that she was just sixteen years old, and the ability to choose was torn from her. “I simply stayed alive.” But she cannot speak of it. In this prison, too, the women must tolerate being abused by men in order to stay alive. Fortunately, Cilka, Josie, and some of the others are selected by a group of men who regularly come to their bunker, viewing them as their property. But at least they ensure that no others do.

Morris’ telling of Cilka’s story is straightforward, unsparing. And difficult to read because it is a work of fiction based upon the life of a woman who actually suffered unimaginable hardship and upon whom unspeakable horrors were visited. But it is also the story of how she did not merely survive. Cilka thrived, because she was determined and resilient, and managed to discover and retain her dignity and humanity. Although she does not believe that she has the capacity to hope or love, Cilka finds herself drawn to those around her who rely upon her strength and leadership. When she finally summons the courage to speak about the past with Yelena, the doctor reveals, “The first day I saw you I felt there was something about you, a strength, a sense of self-knowledge that I rarely see.” And Cilka finally gives voice to the way in which she manages to survive: “I just want to live. I need to feel the pain I wake up with every morning knowing I am alive, and my family aren’t. This pain is my punishment for surviving and I need to feel it, live it.”

Lale Sokolov credited Cilka with saving his life and yet again, Cilka’s compassion and love for a fellow prisoner empower her to heroism. She puts her own desire for freedom aside in order for someone else to be liberated. She refuses to elevate her own circumstances until she knows that her friends in the camp are protected. By then, eight long years have passed.

Eventually, for Cilka, the time to live “without fear and with the miracle of love” arrives. Like her friends Lale and Gita, she finds sustaining love in the most unlikely place.

Like The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Cilka’s Journey is a fictionalized, powerful account of one woman’s hardships during the darkest part of the twentieth century. Also like The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Cilka’s Journey is, at its core, a love story. But it is Cilka’s love for life, coupled with her affection for and willingness to sacrifice for others that are the centerpieces of her story. A a result of choosing to live while imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Cilka suffers from survivor’s guilt. She constantly questions whether she made the right decision and if she deserves to continue living, to ever be truly free again. But when she despairs and believes that she has no strength left, she always manages to keep going, fueled by resilience and courage that surprises no one more than her. Cilka’s Journey is a compelling and inspiring story of bravery and friendship, related by Morris with compassion and tenderness, as well as brutal frankness.

Morris says that the “challenge of working with history is to find the core of what was true and the spirit of those who lived then.” She has succeeded beautifully at conveying the spirit of a girl who was forced to become a woman during the most horrific time in modern history, but managed to do so courageously and altruistically. Cilka’s Journey is an important story, among many that need to be told and re-told, about those who endured and flourished in the face of atrocity.

Also by Heather Morris:

Enter to Win a Copy of Cilka’s Journey

Note: The book may only be mailed to a United States address.

6 Comments

this book is on my tbr

When a new historical is released about the experiences of the Holocaust I read it avidly. The bravery and endurance gives me hope and makes our lives seem trivial. I have read so many and they are all heartbreaking and emotional.

I have read The Tattooist of Auschwitz and was so moved by the fight to survive of those that went through such a horrible experience. It is heartbreaking and inspiring at the same time.

I read The Tattooist of Auschwitz and found it to be a very inspiring book.

I haven’t read the other book. I definitely want to read both of these books.

Thank you so much for the opportunity.