Synopsis:

Synopsis:

Jules Larsen is utterly alone in the world, aside from her one friend, Chloe. But she can’t crash on Chloe’s couch forever. Recently unemployed, heartbroken, and broke, Jules takes a job as an apartment sitter at the Bartholomew, a storied and mysterious Manhattan landmark.

The rules imposed upon apartment sitters are curious and draconian: No visitors, no nights spent away from the apartment, no disturbing the other residents, all of whom are rich or famous or both. But Jules is mesmerized by the splendor of the old building, and the salary she will earn during the three-month assignment is significant — enough to get her back on her feet financially. And, hopefully, she will have secured a new job by the time the assignment ends. So she accepts the terms, ready to leave the past behind her.

As Jules begins getting to know the staff and residents, she finds herself immediately drawn to fellow apartment sitter Ingrid, who comfortingly, yet disturbingly reminds her of Jane, the sister she lost eight years ago. Ingrid confides that the Bartholomew is not what it seems and the dark history hidden beneath its gleaming facade is starting to frighten her. Jules is poised to brush rumors about the building’s history as merely harmless ghost stories. Until she has a strange and frightening encounter with Ingrid, who then disappears.

Concerned about Ingrid’s well-being and determined to find her, Jules digs deeper into the Bartholomew’s dark history and the secrets kept within its walls for decades.

She learns that Ingrid is not the first apartment sitter to go missing from the Bartholomew. And finds herself frantically racing to unmask a killer, expose the true history of the building and its tenants, and escape alive.

Review:

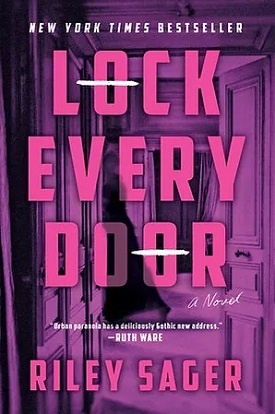

Riley Sager is the pseudonym adopted by Todd Ritter, the journalist, editor and graphic designer turned author of two previous bestsellers, Final Girls and The Last Time I Lied. With Lock Every Door, Sager further cements his reputation for delivering character-driven mysteries that move at a rapid-fire pace and deliver jaw-dropping conclusions in spite of the numerous clues contained in his prose.

Jules is an immediately sympathetic protagonist. At the story opens, she has been laid off from her mediocre, uninspiring job and broken up with her two-timing boyfriend. She is sleeping on her best friend Chloe’s couch and having no luck finding another job. But she notes an advertisement for a an apartment sitter — a three-month assignment in the Bartholomew, an iconic building in the heart of Manhattan with panoramic views of Central Park and a murky history of tragedy. The old building features numerous gargoyles and was the setting for Heart of a Dreamer, the novel that Jules and her older sister, Jane, used to read together. When Jules interviews for the position, she learns she will be living in a sumptuous apartment on the twelfth floor featuring the same view that the lead character in the novel enjoyed. She is informed that the apartment’s owner died recently and the building management want it occupied while the estate is sorted out. Jules finds herself “slightly breathless” as she takes in the view and the opportunity, feeling that after all she has endured, fate has somehow intervened, “even as I’m again struck by that all-consuming thought — I do not belong here.” But being paid to live in her dream apartment is an offer too tempting to turn down, even though Chloe warns her “that it’s all probably too good to be true.”

Sager relates the story through a first-person narrative from Jules that alternates between the present and six successive earlier days until the two timelines merge. When Jules takes up residence in the Bartholomew, she immediately encounters some of the permanent residents, including an aging former soap opera star and the grumpy and stand-offish author of Heart of a Dream. She literally collides with Ingrid, the apartment sitter in the unit directly below the one she is inhabiting, resulting in a visit to her next-door neighbor, Dr. Nike, a surgeon. He’s attractive, reassuring, and well-acquainted with the building, revealing that his great-grandparents were the original owners of the apartment in which he resides. That apartment boasts an odd painting of a snake in the shape of the infinity symbol swallowing its own tail — an ouroboros, signifying the cycle of birth and death. But Jules is attracted to Nick and trusts him.

Every so often, life offers you a reset button. When it does, you need to press it as hard as you can.

Initially, Jules refuses to ascribe to the rumors about the old building. “It certainly doesn’t feel cursed. Or haunted. Or any other menacing label you could put on an apartment building. It’s comfortable, spacious and, other than the wallpaper, nicely decorated.” instantly senses something is “off” at the Bartholomew. But she has disturbing nightmares and thinks she hears noises in the apartment, even though she cannot discern the source of the sounds. When Ingrid begins sending messages to Jules via the dumbwaiter, but suddenly disappears, Jules does not accept the explanation provided for Ingrid’s swift departure. She thought she heard a scream the prior night, and immediately ran to Ingrid’s door to check on her. Ingrid’s odd behavior and cryptic warning, coupled with her shocking exit, compel Jules on a search for the truth about why Ingrid left, as well as the true history of the Bartholomew. She soon discovers that Ingrid is not the only apartment sitter to have abruptly disappeared without a trace. Moreover, she learns that the building long history includes numerous tragedies, suspicious deaths, and unresolved questions about the activities of its tenants.

As Jules’ quest for knowledge proceeds, Sager reveals the heartbreaking family history that inspires her. Jane, her beloved older sister, was last seen getting into a vehicle no one recognized. She never came home. Jules also lost both of her parents, their demise hastened by the loss of their oldest daughter. Jules is determined that Ingrid’s story should have an ending different from Jane’s. At one point, Jules also finds herself faced with a choice about her own story. She realizes that history is not doomed to repeat itself and she can make a different choice than her parents did, regardless of the eventual outcome. But she is required to summon strength and resilience that she never knew for certain she possessed.

Skillfully inserted clues, as well as misdirection feature largely in Sager’s deftly-constructed thriller. He surrounds Jules with an eclectic and interesting cast of supporting players, each with his or her own backstory and motivations for participating in what is actually transpiring at the Bartholomew. Some of those characters are empathetic, even if their ethically leanings are not ambiguous.

Sager keeps readers guessing until nearly the end of the story whether Jules is “prey” or merely “an inconvenience.” Once the truth is revealed, the book’s pace accelerates as Jules must act quickly in order to survive. Because Lock Every Door features an inventive plot, along with compelling characters, it is highly entertaining. Sager delivers a satisfying, if incomplete, resolution to his riveting, Gothic mystery.

Excerpt from Lock Every Door

1

The elevator resembles a birdcage. The tall, ornate kind-all thin bars and gilded exterior. I even think of birds as I step inside. Exotic and bright and lush.

Everything I’m not.

But the woman next to me certainly fits the bill with her blue Chanel suit, blond updo, perfectly manicured hands weighed down by several rings. She might be in her fifties. Maybe older. Botox has made her face tight and gleaming. Her voice is champagne bright and just as bubbly. She even has an elegant name-Leslie Evelyn.

Because this is technically a job interview, I also wear a suit.

Black.

Not Chanel.

My shoes are from Payless. The brown hair brushing my shoulders is on the ragged side. Normally, I would have gone to Supercuts for a trim, but even that’s now out of my price range.

I nod with feigned interest as Leslie Evelyn says, “The elevator is original, of course. As is the main staircase. Not much in the lobby has changed since this place opened in 1919. That’s the great thing about these older buildings-they were built to last.”

And, apparently, to force people to invade each other’s personal space. Leslie and I stand shoulder to shoulder in the surprisingly small elevator car. But what it lacks in size it makes up for in style. There’s red carpet on the floor and gold leaf on the ceiling. On three sides, oak-paneled walls rise to waist height, where they’re replaced by a series of narrow windows.

The elevator car has two doors-one with wire-thin bars that closes by itself plus a crisscross grate Leslie slides into place before tapping the button for the top floor. Then we’re off, rising slowly but surely into one of Manhattan’s most storied addresses.

Had I known the apartment was in this building, I never would have responded to the ad. I would have considered it a waste of time. I’m not a Leslie Evelyn, who carries a caramel-colored attachŽ case and looks so at ease in a place like this. I’m Jules Larsen, the product of a Pennsylvania coal town with less than five hundred dollars in my checking account.

I do not belong here.

But the ad didn’t mention an address. It simply announced the need for an apartment sitter and provided a phone number to call if interested. I was. I did. Leslie Evelyn answered and gave me an interview time and an address. Lower seventies, Upper West Side. Yet I didn’t truly know what I was getting myself into until I stood outside the building, triple-checking the address to make sure I was in the right place.

The Bartholomew.

Right behind the Dakota and the twin-spired San Remo as one of Manhattan’s most recognizable apartment buildings. Part of that is due to its narrowness. Compared with those other legends of New York real estate, the Bartholomew is a mere wisp of a thing-a sliver of stone rising thirteen stories over Central Park West. In a neighborhood of behemoths, the Bartholomew stands out by being the opposite. It’s small, intricate, memorable.

But the main reason for the building’s fame are its gargoyles. The classic kind with bat wings and devil horns. They’re everywhere, those stone beasts, from the pair that sit over the arched front door to the ones crouched on each corner of the slanted roof. More inhabit the building’s facade, placed in short rows on every other floor. They sit on marble outcroppings, arms raised to ledges above, as if they alone are keeping the Bartholomew upright. It gives the building a Gothic, cathedral-like appearance that’s prompted a similarly religious nickname-St. Bart’s.

Over the years, the Bartholomew and its gargoyles have graced a thousand photographs. I’ve seen it on postcards, in ads, as a backdrop for fashion shoots. It’s been in the movies. And on TV. And on the cover of a best-selling novel published in the eighties called Heart of a Dreamer, which is how I first learned about it. Jane had a copy and would often read it aloud to me as I lay sprawled across her twin bed.

The book tells the fanciful tale of a twenty-year-old orphan named Ginny who, through a twist of fate and the benevolence of a grandmother she never knew, finds herself living at the Bartholomew. Ginny navigates her posh new surroundings in a series of increasingly elaborate party dresses while juggling several suitors. It’s fluff, to be sure, but the wonderful kind. The kind that makes a young girl dream of finding romance on Manhattan’s teeming streets.

As Jane would read, I’d stare at the book’s cover, which shows an across-the-street view of the Bartholomew. There were no buildings like that where we grew up. It was just row houses and storefronts with sooty windows, their glumness broken only by the occasional school or house of worship. Although we had never been there, Manhattan intrigued Jane and me. So did the idea of living in a place like the Bartholomew, which was worlds away from the tidy duplex we shared with our parents.

“Someday,” Jane often said between chapters. “Someday I’m going to live there.”

“And I’ll visit,” I’d always pipe up.

Jane would then stroke my hair. “Visit? You’ll be living there with me, Julie-girl.”

None of those childhood fantasies came true, of course. They never do. Maybe for the Leslie Evelyns of the world, perhaps. But not for Jane. And definitely not for me. This elevator ride is as close as I’m going to get.

The elevator shaft is tucked into a nook of the staircase, which winds upward through the center of the building. I can see it through the elevator windows as we rise. Between each floor is ten steps, a landing, then ten more steps.

On one of the landings, an elderly man wheezes his way down the stairs with the help of an exhausted-looking woman in purple scrubs. She waits patiently, gripping the man’s arm as he pauses to catch his breath. Although they pretend not to be paying attention as the elevator passes, I catch them taking a quick look just before the next floor blocks them from view.

“Residential units are located on eleven floors, starting with the second,” Leslie says. “The ground floor contains staff offices and employee-only areas, plus our maintenance department. Storage facilities are in the basement. There are four units on each floor. Two in the front. Two in the back.”

We pass another floor, the elevator slow but steady. On this level, a woman about Leslie’s age waits for the return trip. Dressed in leggings, UGGs, and a bulky white sweater, she walks an impossibly tiny dog on a studded leash. She gives Leslie a polite wave while staring at me from behind oversize sunglasses. In that brief moment when we’re face-to-face, I recognize the woman. She’s an actress. At least, she used to be. It’s been ten years since I last saw her on that soap opera I watched with my mother during summer break.

“Is that-”

Leslie stops me with a raised hand. “We never discuss residents. It’s one of the unspoken rules here. The Bartholomew prides itself on discretion. The people who live here want to feel comfortable within its walls.”

“But celebrities do live here?”

“Not really,” Leslie says. “Which is fine by us. The last thing we want are paparazzi waiting outside. Or, God forbid, something as awful as what happened at the Dakota. Our residents tend to be quietly wealthy. They like their privacy. A good many of them use dummy corporations to buy their apartments so their purchase doesn’t become public record.”

The elevator comes to a rattling stop at the top of the stairs, and Leslie says, “Here we are. Twelfth floor.”

She yanks open the grate and steps out, her heels clicking on the floor’s black-and-white subway tile.

The hallway walls are burgundy, with sconces placed at regular intervals. We pass two unmarked doors before the hall dead-ends at a wide wall that contains two more doors. Unlike the others, these are marked.

12A and 12B.

“I thought there were four units on each floor,” I say.

“There are,” Leslie says. “Except this one. The twelfth floor is special.”

I glance back at the unmarked doors behind us. “Then what are those?”

“Storage areas. Access to the roof. Nothing exciting.” She reaches into her attachŽ to retrieve a set of keys, which she uses to unlock 12A. “Here’s where the real excitement is.”

The door swings open, and Leslie steps aside, revealing a tiny and tasteful foyer. There’s a coatrack, a gilded mirror, and a table containing a lamp, a vase, a small bowl to hold keys. My gaze moves past the foyer, into the apartment proper, and to a window spaced directly opposite the door. Outside is one of the most stunning views I’ve ever seen.

Central Park.

Late fall.

Amber sun slanting across orange-gold leaves.

All of it from a bird’s-eye view of one hundred fifty feet.

The window providing the view stretches from floor to ceiling in a formal sitting room on the other side of a hallway. I cross the hall on legs made wobbly by vertigo and head to the window, stopping when my nose is an inch from the glass. Straight ahead are Central Park Lake and the graceful span of Bow Bridge. Beyond them, in the distance, are snippets of Bethesda Terrace and the Loeb Boathouse. To the right is the Sheep Meadow, its expanse of green speckled with the forms of people basking in the autumn sun. Belvedere Castle sits to the left, backdropped by the stately gray stone of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I take in the view, slightly breathless.

I’ve seen it before in my mind’s eye as I read Heart of a Dreamer. This is the exact view Ginny had from her apartment in the book. Meadow to the south. Castle to the north. Bow Bridge dead center-a bull’s-eye for all her wildest dreams.

For a brief moment, it’s my reality. In spite of all the shit I’ve gone through. Maybe even because of it. Being here has the feel of fate somehow intervening, even as I’m again struck by that all-consuming thought-I do not belong here.

“I’m sorry,” I say as I pry myself away from the window. “I think there’s been a huge misunderstanding.”

There are many ways Leslie Evelyn and I could have gotten our wires crossed. The ad on Craigslist could have contained the wrong number. Or I might have made a mistake in dialing. When Leslie answered, the call was so brief that confusion was inevitable. I thought she was looking for an apartment sitter. She thought I was looking for an apartment. Now here we are, Leslie tilting her head to give me a confused look and me in awe of a view that, let’s face it, was never intended to be seen by someone like me.

“You don’t like the apartment?” Leslie says.

“I love it.” I indulge in another quick peek out the window. I can’t help myself. “But I’m not looking for an apartment. I mean, I am, but I could save every penny until I’m a hundred and I still wouldn’t be able to afford this place.”

“The apartment isn’t available yet,” Leslie says. “It just needs someone to occupy it for the next three months.”

“There’s no way someone would willingly pay me to live here. Even for three months.”

“You’re wrong there. That’s exactly what we want.”

Leslie gestures to a sofa in the center of the room. Upholstered in crimson velvet, it looks more expensive than my first car. I sit tentatively, afraid one careless motion could ruin the whole thing. Leslie takes a seat in a matching easy chair opposite the sofa. Between us is a mahogany coffee table on which rests a potted orchid, its petals white and pristine.

Now that I’m no longer distracted by the view, I see how the entire sitting room is done up in reds and wood tones. It’s comfortable, if a bit stuffy. Grandfather clock ticking away in the corner. Velvet curtains and wooden shutters at the windows. Brass telescope on a wooden tripod, aimed not at the heavens but on Central Park.

The wallpaper is a red floral pattern-an ornate expanse of petals spread open like fans and overlapping in elaborate combinations. At the ceiling are matching strips of crown molding, the plaster blossoming into curlicues at the corners.

“Here’s the situation,” Leslie says. “Another rule at the Bartholomew is that no unit can stay empty for more than a month. It’s an old rule and, some would say, a strange one. But those of us who live here agree that an occupied building is a happy one. Some of the places around here? They’re half-empty most of the time. Sure, people might own the apartments, but they’re rarely in them. And it shows. Walk into some of them and you feel like you’re in a museum. Or, worse, a church. Then there’s security to think about. If word gets out that a place in the Bartholomew is going to be empty for a few months, there’s no telling who might try to break in.”

Hence that simple ad buried among all the other Help Wanteds. I had wondered why it was so vague.

“So you’re looking for a guard?”

“We’re looking for a resident,” Leslie says. “Another person to breathe life into the building. Take this place, for example. The owner recently passed away. She was a widow. Had no children of her own. Just some greedy nieces and nephews in London currently fighting over who should get the place. Until that gets resolved, this apartment will sit vacant. With only two units on this floor, think how empty it will feel.”

“Why don’t the nieces and nephews just sublet?”

“That’s not allowed here. For the same reasons I mentioned earlier. There’s nothing stopping someone from subletting a place and then doing God-knows-what to it.”

I nod, suddenly understanding. “By paying someone to stay here, you’re making sure they don’t do anything to the apartment.”

“Exactly,” Leslie says. “Think of it as an insurance policy. One that pays quite nicely, I might add. In the case of 12A, the family of the late owner is offering four thousand dollars a month.”

My hands, which until now had been placed primly on my lap, drop to my sides.

Four grand a month.

To live here.

The pay is so staggering that it feels like the crimson sofa beneath me has dropped away, leaving me hovering a foot above the floor.

I try to gather my thoughts, struggling to do the very basic math. That’s twelve thousand dollars for three months. More than enough to tide me over while I put my life back together.

1 Comment

Wow! This story, and the Bartholomew, sounds a bit creepy but also intriguing!