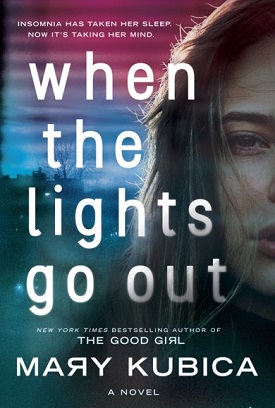

Synopsis:

Synopsis:

Jessie Sloane is attempting to forge a new life for herself, on her own, following the death of her mother. She secures a new apartment and tries to enroll in college courses only to discover that her Social Security number belongs to a dead girl. In light of that revelation, Jessie sets out to discover the truth about her past, exploring documents left behind by her mother, as well as public records that reveal she does not exist. Jessie is still grieving her mother, suffering from the ravages of mourning, including severe sleep deprivation that has taken her far past the point of exhaustion. As a result, Jessie is increasingly unable to distinguish reality from fantasy.

Twenty years ago, two hundred and fifty miles away, another woman’s split-second decision might provides the answers Jessie is seeking. Has Jessie’s whole life been a lie? The truth will shock her to the core of her being . . . is she can live long enough to discover it.

Review:

Mary Kubica is the author of four previous best-selling novels, The Good Girl, Pretty Baby, Don’t You Cry, and Every Last Lie. Her eagerly-awaited new thriller, When the Lights Go Out, again demonstrates why she is among America’s best mystery writers.

Kubica takes readers deep into the psyches of two women: Jessie and her mother, Eden, whose story unfolds twenty years earlier. Eden and Aaron were happily married and wanted to have children. But their struggle with infertility pushed Eden deeper and deeper into an emotional abyss from which she was unable to extricate herself. Their marriage suffered and, under extreme emotional duress, Eden made choices that would define not only the rest of her life, but Jessie’s, as well.

I am Jessie, aren’t I? Am I Jessica Sloane?

Kubica’s narrative alternates between Eden’s story, and Jessie’s present-day description of her quest for the truth about her upbringing and very identity. Because Jessie is suffering from the physical impact of extreme sleep deprivation, she is a wholly unreliable narrator, leaving readers to guess whether she is describing her actual experiences or hallucinating. One thing is certain, however: Jessie needs to cut through her now-deceased mother’s secrets and deceptions before she can make a life for herself. Not only does her Social Security number belong to a dead girl, she has no birth certificate. She cannot obtain a driver’s license, enroll in college, or take any other affirmation steps to establish herself unless and until she unravels the mystery surrounding her identity. Kubica deftly conveys the panic and rear that Jessie feels upon learning that, as a practical reality, she does not exist. But even more importantly, she cannot restore her health and sanity until she knows the truth.

The two women’s stories converge, revealing the extreme heartbreak that led each of them to a dangerous emotional precipice. Kubica injects clues to Jessie’s identity into the story as expertly-timed intervals, but the explosive truth is revealed via a thoroughly satisfying ending.

When the Lights Go Out is a unique, inventive, and moving story from Kubica, told in the style readers have come to love so well — with compassion, insight, and great empathy for her characters, despite their significant flaws. Readers will find themselves unable to put When the Lights Go Out down until they know the answers Jessie seeks and understand Eden’s motivations.

Excerpt from When the Lights Go Out

JESSIE

Mom had two wishes when she died, ones she let slip in the last brief moments of consciousness before she drifted off to sleep, a sleep from which she would never wake up. One, that she be cremated and lobbed from the back end of the Washington Island Ferry and into Death’s Door. And two, that I find myself and figure out who I am. The second hinged on the esoteric and didn’t make obvious sense. I blamed the drugs for it, that and the imminence of death.

I’m nowhere near accomplishing either, though I filled out a college application online. But I have no plans of parting with Mom’s remains anytime soon. She’s the only thing of value I have left.

I haven’t slept in four days, not since some doctor took pity on me and offered me a pill. Three if you count the one where I nearly nodded off at the laundromat waiting for clothes to dry, anesthetized by the sound of sweaters tumbling around a dryer. The effects are obnoxious. I’m tired. I’m grumpy. I can focus on nothing and my reaction time is slow. I’ve lost the ability to think.

Yesterday, a package arrived from UPS and the driver asked me to sign for it. He stood before me, shoving a pen and a slip of paper up under my nose and I could only stare, unable to put two and two together. He said it again. Can you sign for it? He forced the pen into my hand. He pointed at the signature line. For a third time, he asked me to sign.

And even then I scribbled with the cap still on the pen. The man had to snatch it from my hand and uncap it.

I’m pretty sure I’ve begun to see things too. Things that might not be real, that might not be there. A millipede dashing across the tabletop, an ant on the kitchen floor. Sudden movements, immediate and quick, but the minute I turn, they’re gone.

I keep track of the sleepless nights in the notched lines beneath my eyes, like the annual rings of a tree. One wrinkle for each night that I don’t sleep. I stare at myself in the mirror each day, counting them all. This morning there were four. The surface effects of insomnia are even worse than what’s going on on the inside. My eyes are red and swollen. My eyelids droop. Overnight, wrinkles appear by the masses, while I lie in bed counting sheep. I could go to the clinic and request something else to help me sleep. Some more of the clonazepam. But with the pills in my system, I slept right on through Mom’s death. I don’t want to think about what else I’d miss.

At McDonald’s, I’m asked if I want ketchup with my fries, but I can only stare at the worker dumbly because what I heard was, It’s messed up when boats capsize, and I nod lamely because it is disastrous and sad, and yet so out of left field I can’t respond with words.

It’s only when he drops a stack of ketchup packets on my tray that my brain makes the translation, too late it seems because I hate ketchup. I dump them on the table when I go, the mother lode for someone who likes it. On the way out the door I trip, because coordination is also effected by a lack of sleep.

Two hours ago I dragged my heavy body from bed after another sleepless night, and now I stand in the center of Mom and my house, deciding which of our belongings to take and which to leave. I can’t stand to stay here much longer, a decision I’ve come to quickly over the last four days. I’ve spoken to a realtor already, figured out next steps. First I’m to pack up what I want to keep, and then everything else will be sold in an estate sale before some junk removal service tosses the rest of our stuff in the trash.

Then some other family will move into the only home I’ve ever known.

I’m eyeing the sofa, wondering if I should take it or leave it, when the phone rings. “Hello?” I ask.

A voice on the other end informs me that she’s calling from the financial aid office at the college. “There’s a problem with your application,” she says to me.

“What problem?” I ask the woman on the phone, afraid I’m about to be cited for tax evasion. It’s a likely possibility; I’d left blank every question on the FAFSA form that asked about adjusted gross income and tax returns. I might have lied on the application too. There was a question that asked if both of my parents were deceased. I said yes to that, though I don’t know if it’s true.

Is my father dead?

On the other end of the line, the woman asks me to verify my social security number for her and I do. “That’s what I have,” she says, and I ask, “Then what’s the problem? Has my application been denied?” My heart sinks. How can that be? It’s only a community college. It’s not like I registered for Yale or Harvard.

“I’m sure it’s just a weird mix-up with vital statistics,” she says.

“What mix-up?” I ask, feeling relieved for a mix-up as opposed to a denied application. A mix-up can be fixed.

“It’s the strangest thing,” she says. “There was a death certificate on file for a Jessica Sloane, from seventeen years ago. With your birthdate and your social security number. By the looks of this, Ms. Sloane,” she says, and I amend Jessie, because Ms. Sloane is Mom. “By the looks of this, Jessie,” she says, and the words that follow punch me so hard in the gut they make it almost impossible to breathe. “By the looks of this, you’re already dead.”

And then she laughs as if somehow or other this is funny.

Comments are closed.