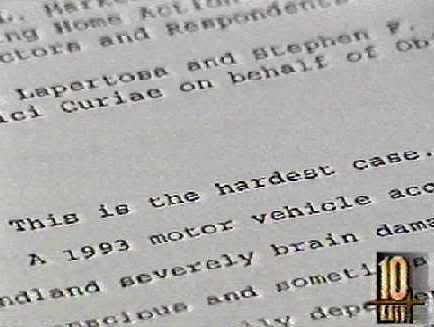

“This is the hardest case.” So said the Third District Court of Appeal on February 24, 2000. It was the very first sentence of its lengthy ruling. And, in my opinion, that sentence made about as much sense as did the remainder of their nonsensical decision, which included a remand back to the trial court. In other words, a directive to go try Conservatorship of Wendland again.

“This is the hardest case.” So said the Third District Court of Appeal on February 24, 2000. It was the very first sentence of its lengthy ruling. And, in my opinion, that sentence made about as much sense as did the remainder of their nonsensical decision, which included a remand back to the trial court. In other words, a directive to go try Conservatorship of Wendland again.

I remember reading that part and thinking, “Over my dead body. Literally.”

There was never anything hard about this case from a legal standpoint, especially after that day in the summer of 1995 when we (me, the managing partner at my firm, Rose Wendland’s then-counsel, W. Stephen Scott, and Judge McNatt) visited Robert at Lodi Memorial Hospital. Judge McNatt said that if he was going to render a decision about the man’s life, he wanted to see the man in person.

What was most striking about that visit were two moments in particular: The first was when we were waiting for the judge to arrive. We were discussing Robert’s abilities and Steve Scott mumbled something along the lines of “a monkey can do that.” I was repulsed.

The second was when we — the judge included — were standing in the hospital corridor watching Robert maneuver his wheelchair. He crashed into a linen cart. One of the aides started toward Robert, intent on assisting him. But the physical therapist stopped her. I’ll never forget what she said: “No. Let him problem-solve.” Sure enough, after a few moments, he figured out how to back up, change the direction of the wheels, and continue down the hall.

The significance was not lost on Judge McNatt, whose eyebrows flew up when he heard the word “problem-solve.” He watched Robert intently during that visit.

For me, it confirmed that this case was a legal “no-brainer” in terms of how the court should rule.

Which is probably part of the reason that the vociferous battle that seemed like it was never going to end was so taxing.

After the trial ended, Rose got a new attorney. He wasn’t new to the case, though. He was none other than Lawrence Nelson, who calls himself a “bioethicist.” He is a professor at Santa Clara University. During the trial, he served as an “expert” witness for her, but I had a great deal of fun skewering him on cross-examination.

It was particularly satisfying because I actually met Nelson well before the trial and under unusual circumstances.

I had been informed of his participation in the case, but had never heard of him. Then one day I received an advertisement in the mail for an MCLE (Mandatory Continuing Legal Education) course offering in Sacramento. Among the topics was to be end-of-life decisionmaking and among the presenters? You guessed it: Nelson. So I immediately enrolled. I had never met him and he had never met me, so I figured I could sit in the back of the class, unobtrusively checking him out and taking notes on his commentary.

During the break, I was out in the hallway and walked right into my nemesis, Steve Scott. Foiled! I knew that he would tell Nelson I was there, if he hadn’t already.

Predictably, Nelson played to me after that, looking at me to punctuate the points he was making and plainly attempting to intimidate me with his self-acclaimed expertise.

And then the moment came. He was responding to a question from an audience member about how to get a feeding tube removed when the patient’s life should no longer be prolonged. He said the words that I will never, ever forget. Even as I sit here typing this, I can hear the faux authority in his voice and see the sneer that was on his face. He looked right at me, as he said, “You want a feeding tube pulled? You call me. I’ll get it pulled.” And then there was a very pregnant pause, as he made sure I absorbed the meaning of his words before he moved on to take the next question.

He was just like a schoolyard bully who draws the line on the playground and dares the new kid to cross it.

And all I could think was, “Oh, buddy, you have no idea what you have just done.”

Because I knew that there was no way I was goever ing to allow his arrogance and pomposity to get the better of me, my clients, or my case. I determined right there to make him regret ever uttering those words.

And I did.

The Third District Court of Appeal oral argument was unbelievable. Recognizing the seriousness of the case, the justices had doubled the amount of time normally allotted for oral argument. The meda was assembled, as usual.

I was a moot court finalist at McGeorge School of Law, which means that I got a lot of invaluable training in the art of appellate argument. And one of the things that was stressed to me by my professors and coaches was this: If you are not prepared to step up to the podium with nothing in your hands, you are not prepared to argue your case. It is as simple as that. You must know the facts of your case, as well as the legal precedents which support and militate against your clients’ arguments, cold. The appellate court is not the place to stop and look up the name of a case, review its holding, or double-check the facts. Appellate argument is all about thinking on your feet and being flexible because appellate justices rapid-fire questions at you from all directions and they always interrupt you, so you cannot plan to give a speech. You come up with a one-sentence opener and hope you get through it (out of all the appellate arguments I’ve handled, I’ve never completed my opening sentence yet) before they stop you and ask a question that is, predictably, diametrically opposed to whatever aspect of the case you are thinking about at that moment.

I watched with amusement as Nelson and James Braden entered the courtroom with boxes of books, binders, and files. (Braden had taken over representation of Robert from Doran “Oh, I’ve lost myself” Berg, the Stockton Public Defender appointed to represent his interests at trial.) They didn’t bother to check the docket, apparently, nor did they check in with the clerk of the court. They just went right up to counsel table and proceeded to unload their boxes. But there was an argument scheduled before ours, so the clerk had to come over and instruct them to pack it all up again.

I watched with amusement as Nelson and James Braden entered the courtroom with boxes of books, binders, and files. (Braden had taken over representation of Robert from Doran “Oh, I’ve lost myself” Berg, the Stockton Public Defender appointed to represent his interests at trial.) They didn’t bother to check the docket, apparently, nor did they check in with the clerk of the court. They just went right up to counsel table and proceeded to unload their boxes. But there was an argument scheduled before ours, so the clerk had to come over and instruct them to pack it all up again.

Did I mention that Nelson and Braden graduated, respectively, from Yale and Harvard Schools of Law?

Braden appeared completely unversed in courtroom etiquette. He refused to yield to the justices on numerous occasions, attempting to talk over and interrupt them. Finally, he was so out of control that Justice Arthur Scotland stopped the argument to explain the rules.

“Mr. Braden, let me tell you how it works here. We get to interrupt you. You do not get to interrupt us.”

I’ve never seen anything like it.

I was at my counsel table all by myself with just my yellow legal pad and a pen, jotting down key words as they spoke so that I would be ready for rebuttal. Just as I was making a note, I felt something fall into my hand. It was my gold chain with the heart and cross pendants. The clasp had come open. I couldn’t put it back on during the argument, so I figured I would just put it into the pocket of my jacket.

There was just one small problem with that plan: I was wearing a brand new suit and had forgotten to cut open the pockets! So I just held the necklace in my left hand as I continued writing a word here or there with my right and then returned to the podium to be further grilled by the justices. I didn’t realize how tightly I was grasping it.

When the argument was over, I remembered the chain. When I opened my hand, I saw that I had clutched it so tightly during the argument that there was an imprint of the cross on my palm.

Happenstance?

No.

To be continued . . .

Comments are closed.